For those who claim not to be ‘artistic,’ there’s often a myth that surrounds the act of creation. Some put it down to the channelling of spirits, or visions from dreams. More often than not, discipline plays the biggest role, but where’s the fun in that?

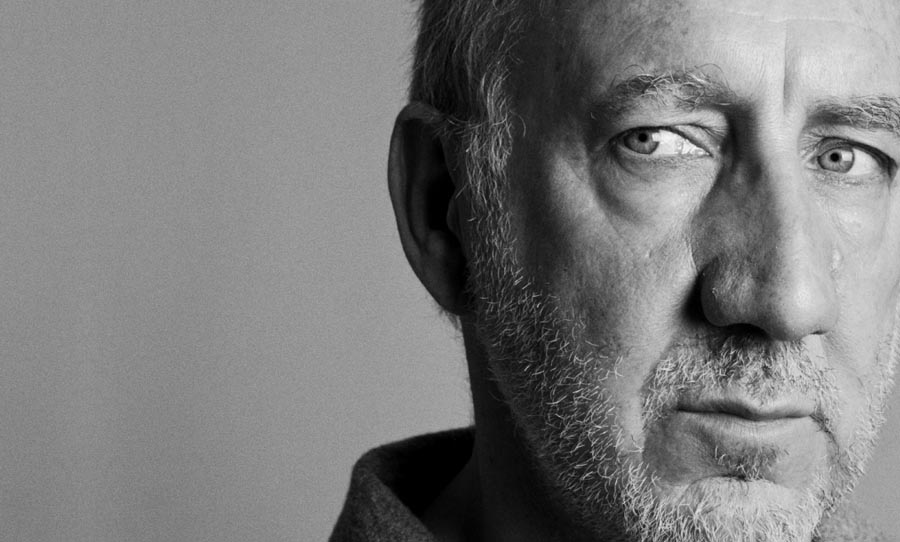

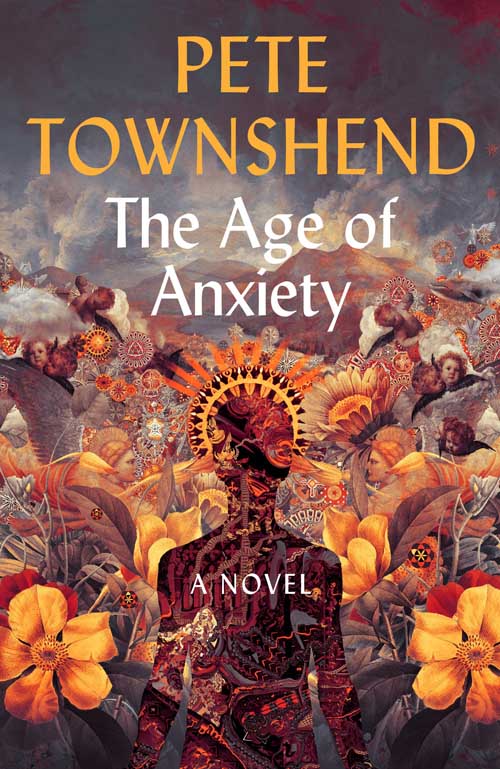

In The Age of Anxiety (Hachette), Pete Townshend explores the former proposition – the divining of inspiration through ethereal sources – through his protagonist, Walter. The author, of course, has climbed to the peak of rock stardom with The Who and his debut novel reflects a complicated perspective on fame, ego and the relationship between creation and the psyche.

Pete Townshend’s debut novel, The Age of Anxiety is a complex tour through the creative mind, from stability to mania, examining the impact it can have on human relationships.

The narrator, Louis Doxtader is an ageing art dealer and roams like a lone wolf throughout this tale. Though intertwined with all characters, Louis’ purpose is shed light on Walter – the young leader of a rock band, Big Walter and His Stand. The band is well-established, but has an artistic scope that fails to extend beyond their pub following.

In Louis’ capacity as an art dealer, he comes into contact with Maud – the wife of an actor who lost his mind on the set of a film shot in England’s Lake District and stayed there for fifteen years, sleeping rough and creating exquisite, apocalyptic charcoal drawings. The former actor, now artist, who goes by the name Nikolai Andreévich became a lucrative client for Louis.

Louis is no stranger to episodes of mental health struggles too. His history with drugs and hallucinations made him sensitive to connections that artists had with their subconscious. So when Walter tells him of his own auditory spectres, Louis encourages him to channel these soundscapes into his art.

Walter enters into an extended period of musical hiatus and it’s here that Townshend is able to make some of his most telling observations about the darkness of the creative mind. He reflects on the era of Walter’s anxious solitude:

“For fifteen years of creative lock-down he had continued to be steadily filled with their emotions, their rage, fear, shame, resentment and tendency to judge, their need to try to shift the blame for everything that was wrong with the world…”

Further, as Louis reflects on the role of younger generations in the world, you can’t help but hear a world-weary author speaking through his narrator, “Indeed, Walter’s contemporaries carried the weight of the planet, not just of their own immediate environment.”

These canny observations that can only come from a breadth of experience – and making a life pursuing art and all its accompanying meditations – are the threads that stitch this book together. As a narrative, though, there’s a lack of cohesion.

For instance, it’s hard to look past the single dimension in which the female characters live in The Age of Anxiety: uniformly beautiful objects of sexual desire and mystery. In the scene where Walter’s band implodes, the three main female characters – Siobhan, Selena and Floss – are all lined up to tempt Walter in various ways. Beyond this purpose, these characters bring little to the table.

Then there are the descriptions of the soundscapes that assail Walter. Seemingly injected ad hoc, they do provide some context as to Walter’s eventual musical direction, but do little to connect elements of the plot.

Townshend’s meditations on creativity and the darker visions that haunt artists can be genuinely insightful. Themes of patience, perseverance and the ability to channel the emotional rollercoaster of life through art have the ring of truth.

But in shoehorning these thoughts into a melodrama, the message is somewhat confused and diluted. In the postscript, Townshend alludes to the possibility of realising The Age of Anxiety as an opera, or Son et lumière. These kinds of multi-sensory experiences might more appropriate forums for these concepts.

The Age of Anxiety is out now via Hachette.