I’d never advise anyone to drag themselves through the septicity of addiction or depression. Though admittedly, there is something delicate and fascinating about the tortured artist.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 10. Grab your copy here.

From the steps of her Camden flat, she departed amidst the rapture that donned her career from beginning to heartbreaking end. Like the fading of something bright sat too long in the sun, so too was the mystique of a woman beneath the strobe of inquisition.

The world watched, filmed and photographed the body of Amy Winehouse as she crossed the threshold of her home and into a private ambulance – this the last picture of a voice unrivalled – a voice of vulnerability, feminine power and supreme technique. It seems even in death, our thirst for the wayward surpassed any sort of human decency. A final act of callous invasion.

Hers was a heart worn on the sleeve. Her songs detailed relationships in turmoil and a woman battling to remain human in an inhuman world. Where the words of most artists exist in our own romantic conjurings, Winehouse’s life played out before us in the morning paper. We matched her lyrics to sinister photographs devoid of any positive intent. Her poetics and soul became a contorted, grainy face of cocaine and debauched alcoholism.

At the height of Amy Winehouse hysteria, things got ugly. A sort of savage dog pit, media outlets resorted to blow-for-blow insults, each more humiliating than the last. We were watching Janis Joplin drink herself into oblivion again, but from this bullying came a strangely intoxicating elation – our collective hindsight a blurry 20/20.

So what was it? Why are we so obsessed with the wayward rock romantics? And why, in turn, do these artists subject themselves to the dark troughs of addiction?

As an audience, there’s a notable fixation attached to vulnerability. No one likes airing their dirty laundry. We tend to keep those heartfelt conversations for trusted friends and family – a time to lament, consider and overcome. So when a stranger does so with sincerity, especially one with artistry or the ‘famous’ tag attached, we become drawn to what is essentially a secret. It’s a bond with the oeuvre of an artist, held as a romantic ideal.

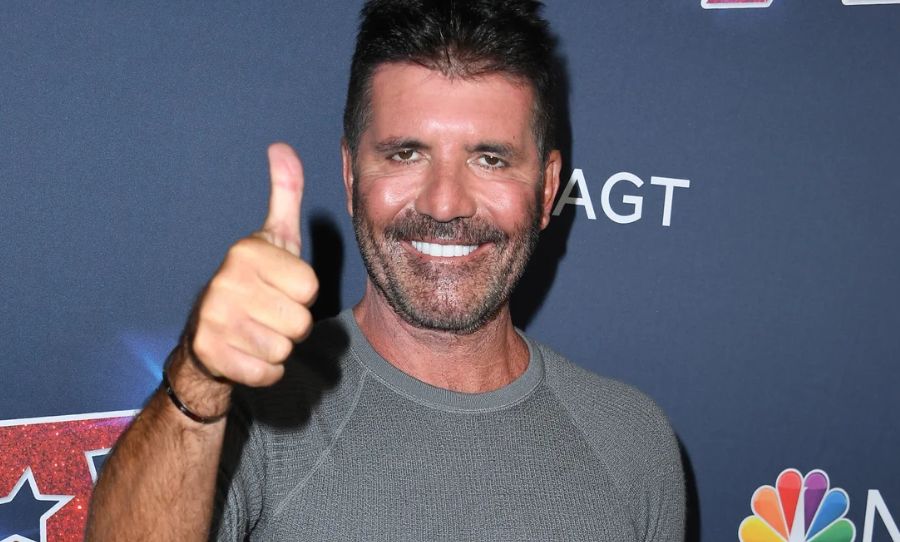

When considering the modern embodiments of this fixation, in people like Amy Winehouse or Pete Doherty, the media’s representation of the tortured artist isn’t far behind. Plagued by drug addiction and the might of conjecture, the tabloid’s harassment and bullying seemed to fit an eerily familiar story arc of build ‘em up, break ‘em down.

Presented in nonchalance, these artists live in a lavish world of no rules or repercussions. This plays on society’s fascination with controversy and death, something foreign and unattainable to the average community.

While Winehouse’s addiction did lead to her eventual death, the ‘death’ I’m referring to is that of the unknown – what will happen next? Will Pete die soon? Who will he drag down with him?

Although it’s been years since watching any sort of mainstream news program, I can still remember the painstaking method of its presentation. It goes something like: hurricane, terrorist, murder, what’s going to give you cancer, sport, weather, then a cute story about a labrador saving the ducklings from lollipop pond.

Deterioration and the macabre, that’s what gets our attention. It’s our innate human responses to these stories that create opinion, and it’s the clashing of these opinions that create effective tabloid content. They don’t care if they hurt your feelings, or that of your favourite artists. They just care that you pick a side.

While I’m quite willing to write off the tabloid’s representation of the artist as plain money swindling and that their concern is surface level at best, it’s the human responses that create the aura around an artist. It’s “Leave Pete alone!” vs. “Pete’s a smelly junkie, he looks like a chewed up candle”. This nasty speculation and mainstream mania are obvious contributors to poor mental health and addiction, though could there be more to the tortured artist than just wayward partying? Are there redeeming qualities to the drug-addled poet, holed up in his North London flat?

While mainlining heroin is certainly not advised or at all desirable, there must be a reason why myself, and many like me, romanticise the pariah poets of art. For conversations sake and a looming word minimum, let’s investigate the grimy flipside of the coin; the insular mind of the artist.

It’s 19th century Paris, croissants butter the air, French stuff is happening. Though unfortunate for us, we’re sat across from a smelly drunk. His odor plagues the local café. Like a troll picking at the bones of its last meal, he toils away on a bottle of absinthe. A poet scumbag of the highest order.

Paul Verlaine is widely considered the greatest French poet of the fin de siècle. Though where his esteem swells, so too does a life of debauched insanity. This alcoholic, wife-beating, drug taking, syphilitic jailbird scraped by on a pittance of success and moral righteousness.

Though amidst this life of chaos, Verlaine penned Les Poètes Maudits – The Cursed Poets. Within, Verlaine rivals his own absurd existence and creative output to that of contemporaries like Rimbaud and Mallarmé. Through society’s inability to understand their art, furthered by a philistinic bourgeois, these wayward degenerates were cursed. The term poètes maudits is now coined as a poet living against society. A pariah of the most isolated.

Verlaine’s contemporaries and influences are among the world’s greatest writers, most of which suffered from debilitating addictions and mental health issues. Though he suggests they lived for this existence because without it, their art wouldn’t be. These illnesses and contextual restraints are tools in their own martyrdom. After all, it’s their turbulent lives we remember most fondly, and through this we discover their art – a stark reminder of our fixation with death.

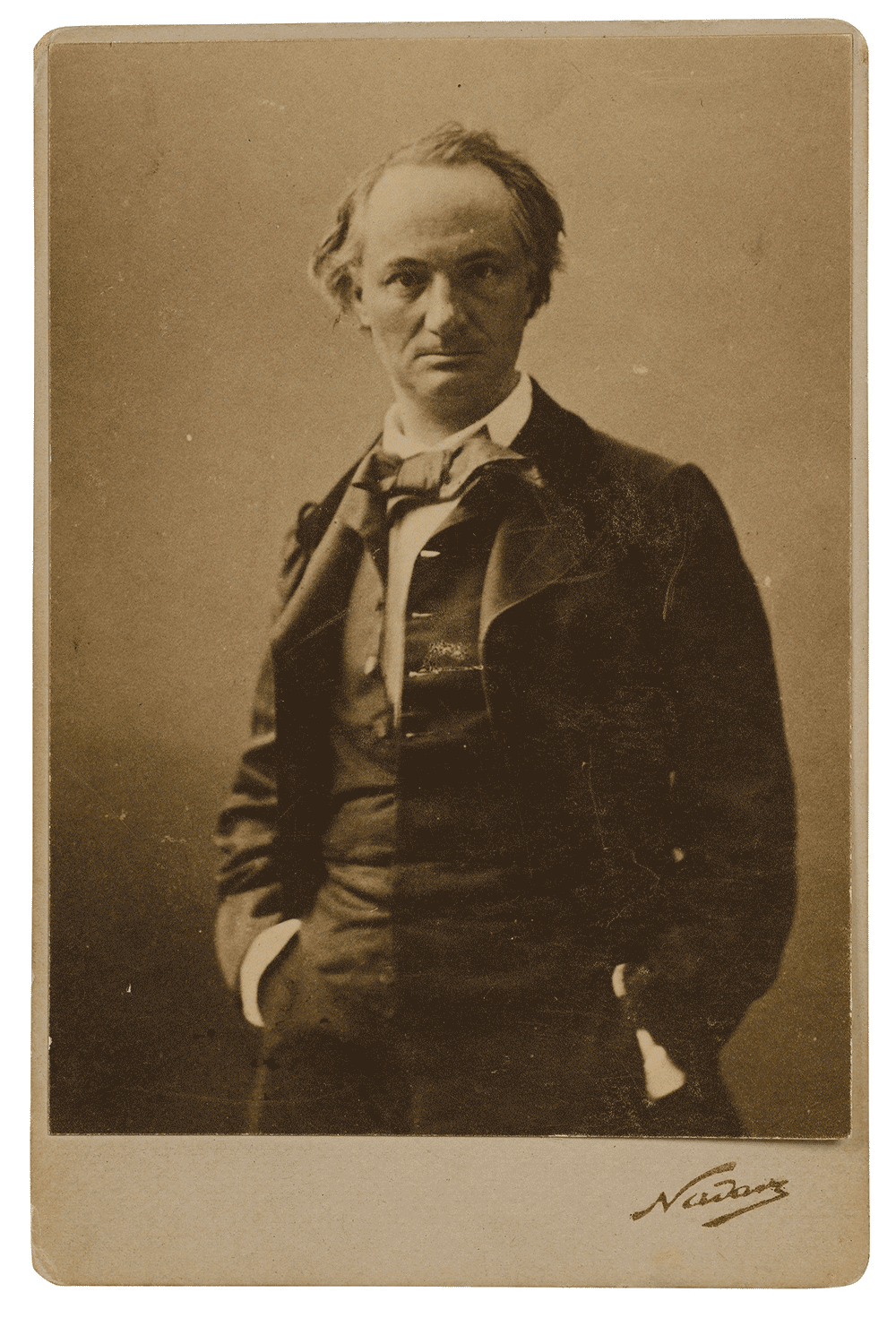

Midst these influences were Charles Baudelaire; opium addict, syphilitic and genius. Exploring hopes, dreams, failures and sin, he sorts out beauty from malevolence. Where tradition had seen the bearing of emotion through the splendour of the natural realm, Baudelaire found agency in the paradoxical. Having lived a life cut short by disease, Baudelaire’s biggest feats were The Flowers of Evil and the pioneering translation of fellow addict and literary extraordinaire, Edgar Allen Poe.

“Baudelaire inaugurates two different conceptions of the cursed poet: the man who is destroyed by society’s contempt for his art and his very being, and the one who deliberately and heroically destroys himself – in Poe’s case with alcohol – for his invaluable art’s sake.”

– Algis Valiunas

Baudelaire and Poe sought intoxication to extinguish pain and deaden the sober world, loosening the imaginative realm of inebriation, a place familiar and fruitful in its reoccurrence. While societal advancements would now see this as a clear case of self-destructive, manic-depressive addiction, these rituals laid the creative bed for writing unparalleled in human existence.

I’d never advise anyone to drag themselves through the septicity of addiction or depression. Though admittedly, there is something delicate and fascinating around the tortured artist. While I can’t exactly put my finger on it, I think it has something to do with the legitimacy of their pain. They’ve just been there, and you haven’t.

I have no grandiose statements for you, no incredible reasons why. Just the most profoundly sad thing I’ve ever read from a man that embodied those torturous depths of creativity:

“When the lighting is bad, I’m the man with the most”

– Rowland S. Howard

This article appears in Happy Mag Issue 10. Grab your copy here.