When you think back to the music of the ’60s, memories tend to be dominated by the rockers of the British Invasion. But in newly independent Jamaica, there was an entirely new sound that was set to be exported all over the globe. What started with ska, morphed into reggae, which in turn spawned dub.

The recorded music of Jamaica relied on the same technical building blocks that were used in studios elsewhere, but pioneers like King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry expanded the vernacular of effects, infusing mixing techniques with playful experimentalism. The once serious business of being behind the console was transformed into an open-ended sonic adventure.

At the peak of the British Invasion, an entirely different sound was brewing in Jamaica. This is the story of how the pioneers of dub revolutionised the studio.

A different rhythm

As the rock’n’roll revolution was sweeping through America in the 1950s, ska was emerging in Jamaica. The blend of rock, rhythm and blues, and styles that were native to the Caribbean like calypso went into the mixture that made up ska.

The distinguishing feature? The rhythmic accenting of the weaker two and four beats of the bar, rather than the one and three: a staple of rock ‘n’ roll. This characteristic, coupled with a lively tempo, made for uplifting, energetic tunes that were made for the dancefloor.

This crucial element in the DNA of Jamaican music was passed onto ska’s progenitors in the following decade. Rock steady continued the off-beat emphasis but at a slightly slower tempo, as did reggae, but with the addition of the distinctly swung ‘double-chop’ (listen to any reggae jam and try not to hypnotically sway from side-to-side in lockstep with the guitar’s rhythm).

The sound system

These genres also conformed to the wider definition of pop music: lyric-based, melodic, and relying on structure (especially the music of reggae icons like Bob Marley). Dub, however, took on the rhythmic language of Jamaica and remixed it.

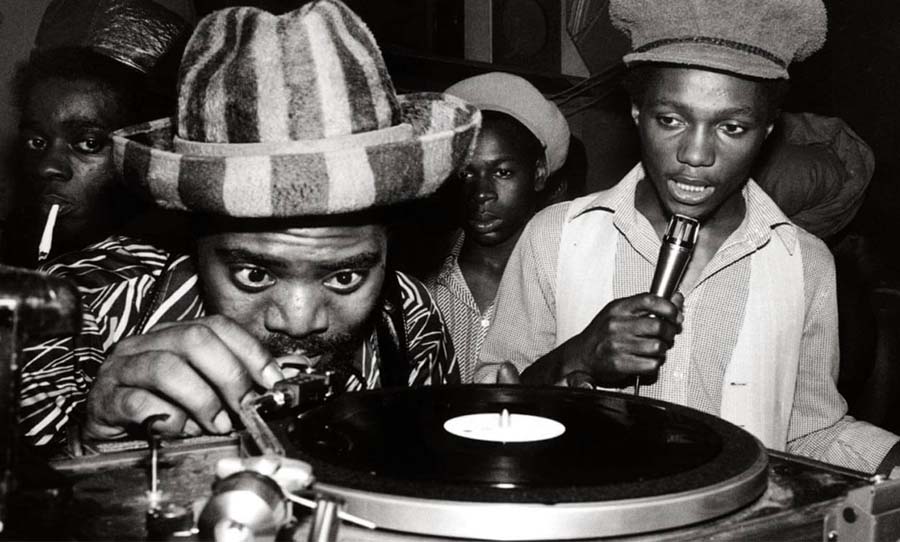

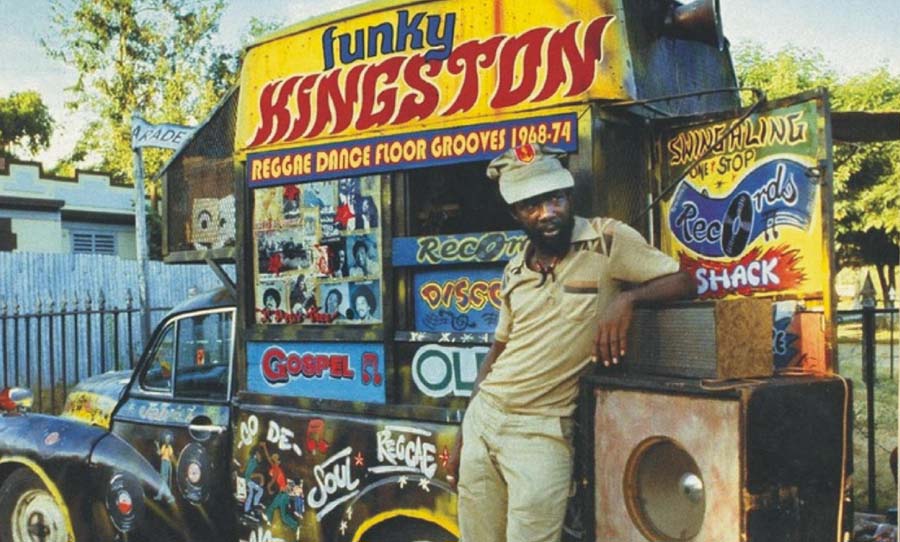

It was also on the streets of Jamaica that the phenomenon of live DJing first took root. Since the 1940s, sound systems were loaded onto trucks and set up in the streets, blasting recorded rhythms (instead of live bands) throughout the landscape.

The sound system tradition played an essential role in the development of dub: remixed instrumental versions of the B-sides of reggae singles—heavy on the bass to blast through sound system sub-woofers—was perfect fodder for live DJs, who would rap over the tracks.

In the studio

By the early ’70s, the Jamaican record industry was going from strength-to-strength, with star acts like Bob Marley and Toots and the Maytals finding themselves on the world stage and sound systems ringing out all over the island nation. Significantly, studio technology had reached a point where artistry could transcend the technical—dub producers like King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry were perfectly poised to make a splash.

King Tubby acquired a 12-channel MCI mixing desk for performing dub mixes. As Kirk Digiorgio says in a Red Bull Music Academy article:

“…there was plenty of scope for individual instruments to be muted and for elements of the drum kit – such as the crucial snare/rimshot – to have their own channel. Each channel had a dedicated reverb send, which enabled reverb to be placed solely on individual elements without muddying the mix as a whole.”

Performing on the console

A seemingly low limit of available channels was more than enough for King Tubby to completely reimagine a song. This process of creating a dub mix also recast the studio as a means of performance. Classic dubs like King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown (featuring the melodica performance of Augustus Pablo) showcase Tubby’s ability to marry the science of engineering with the evocative art of sound design. Note the expertly timed delay throws, introducing triplets into the traditions of Jamaican rhythms.

The elements of a dub performance are all available on a traditional mixing desk. Not far from the top of the channel strip resides the EQ section, which is important for aggressively filtering the bottom end of snare, to create a ghostly, ethereal tone. It’s equally important for bringing down the top end of the delay return channel to conjure up characteristically lo-fi repeats.

Even the utilitarian mute button on a channel strip is used to great effect. Even though dubs are largely instrumental in style, grabbing snippets of a vocal, muting it quickly, then hitting it with a delay or reverb is a trademark of the idiom. These techniques and more are shown in the snippet below by King Jammy (who would later adopt digital technology, becoming one of the leading voices in dancehall music).

Even for people who are unfamiliar with the musical characteristics of dub, it’s impossible to escape its influence. It played an outsized role in shaping how producers and musicians approach electronic music; deriving from ‘double’, dub takes preexisting material and resculpts it in new and interesting ways. This is the cornerstone of the remix, in any style. This invention of Jamaica continues to inspire 50 years on from its birth and just like the traditional rhythms it paid tribute to, it still sounds effortlessly fresh.