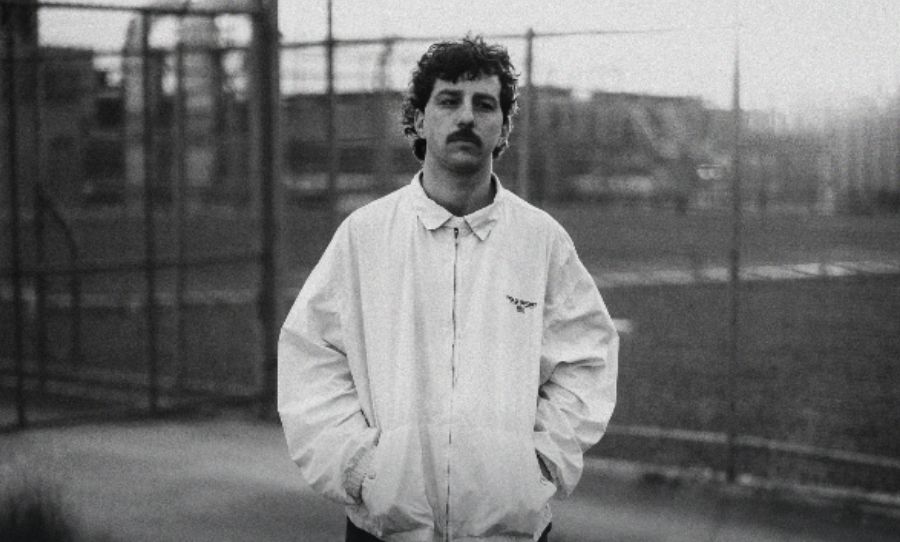

Spearheaded by Auckland-based ex-club DJ Michael Fredrickson, Groove Incorporated’s new track, Aotearoa Reggae, is a groove-packed homage to reggae’s deep cultural roots in Aotearoa.

Reggae has long been a part of New Zealand’s soul—alongside the haka, whānau connections, and communal pride. Outside of Jamaica, New Zealand arguably boasts one of the, if not the most devoted reggae followings in the world.

For Māori and Polynesian communities, reggae wasn’t just music—it was a movement and a powerful force for unity and social change. In its early days, reggae in Aotearoa was defined by trailblazers like Herbs, The 12 Tribes of Israel, and Dread, Beat and Blood.

These acts didn’t just make music—they amplified voices. Tracks like Herbs’ French Letter rallied against France’s nuclear testing at Mururoa Atoll, while the genre became the soundtrack for Māori activists fighting for land rights and the revival of Te Reo Māori.

These acts didn’t just make music—they amplified voices. Tracks like Herbs’ French Letter rallied against France’s nuclear testing at Mururoa Atoll, while the genre became the soundtrack for Māori activists fighting for land rights and the revival of Te Reo Māori.

Reggae was a rallying cry, a platform for the socially and politically marginalised, and a powerful tool for change.

By the 1990s and early 2000s, the genre began to evolve, blending with New Zealand’s vibrant festival culture. Reggae became synonymous with summer, the beach, and—somewhat controversially—the BBQ.

The once militant, message-heavy tone of the ’80s gave way to sunnier, more carefree vibes.

Reggae became the soundtrack for summer feel-good riddims that now dominate outdoor stages across the country.

For over a decade, the annual One Love festival has been a must-attend event for reggae fans celebrating music, summer, the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) and Bob Marley’s birthday (both Feb. 6), and often the subtle aroma of weed.

Following the success of Band of Gold, Aotearoa Reggae keeps one foot planted in reggae tradition while stepping into uncharted sonic territory.

Fredrickson’s recent pilgrimage to Jamaica, where he visited Bob Marley’s childhood home and the legendary Tuff Gong studios, undoubtedly played a pivotal role: “Sitting in the main room of that iconic studio gave me huge inspiration for moving the project forward,” he says.

His hands-on approach ensures that Aotearoa Reggae feels both authentic and innovative.

The track pulses with a classic one-drop rhythm—a hallmark of reggae’s heartbeat—while layering elements of lovers rock, dub, and touches of modern dancehall.

Opening with a sharp, snappy snare-drum roll, Aotearoa Reggae dips into that steady one-drop groove, but with a deep, syncopated bassline that nods to Robbie Shakespeare.

Much like how reggae has united people across social and racial divides – musically – the track is a clever marrying of contrasts.

Fredrickson masterfully combines a conventional piano skank and bubbling Hammond organ riff with the edgy, Nicki Minaj-like attitude of lead vocalist Honey-B-Sweet.

These are balanced by silky-smooth soul-infused backing vocals, reminiscent of the rich, choral depth of the Wailers.

The production adds subtle dub echoes and percussive accents, infusing a fresh dynamic into its warm, vintage-inspired sound.

It’s easy to get carried away into musical nirvana with the track’s groove and infectious melodies, but what really makes Aotearoa Reggae stand out like none before is the track’s history lesson – a vital reminder of the reggae pioneers who’s legacy is easy to take for granted.

Conscious of honouring the genre’s roots with historical accuracy, Fredrickson drew heavily from Jennifer Cattermole’s 2004 master’s thesis, which charted reggae’s journey from niche to national phenomenon.

Fredrickson highlights the genre’s defining features and milestones: from the genre’s evolution from the Jamaican-inspired sounds embraced by Māori and Polynesian communities in the late ’70s (sparked by Bob Marley’s 1979 concert at Western Springs Stadium: “but 79 is when it all began”), through to the cross-over festival-ready jams.

Along the way, we are reminded of the genre’s uniqueness in his part of the world: the signature percussive guitar skank (“Pacific strum”) and the genre’s universal appeal, cutting across age, race, and socioeconomic boundaries (“found in Porirua to Remuera”).

New Zealand reggae, particularly its more recent iterations, has not been without its critics. “BBQ” often used as a polite way of saying “lame,” and that sentiment hasn’t escaped influencing the musical elite.

While this stigma is acknowledged in passing, the focus of the story remains firmly on the genre’s many achievements: “Won many a Tui (award), thanks to Tiki, Freddy, and now L.A.B.”

Aotearoa Reggae delivers a compelling message, backed by historical evidence, that reggae music in the land of the long white cloud is here to stay.

Whether you’re drawn to the militant riddims of roots reggae, the hypnotic pulse of dub, or the crossover appeal of festival anthems, Aotearoa Reggae offers something for everyone.

It’s history, culture, groove and an optimistic future in one irresistibly skanking package.

Turn it up and let the riddim move you.