If you draw a dot in the middle of a map of Florida, you’ll probably land on the city of Gainesville. The small town seems an unlikely setting for a tale of intense camaraderie, coupled with the redefining of artistic boundaries.

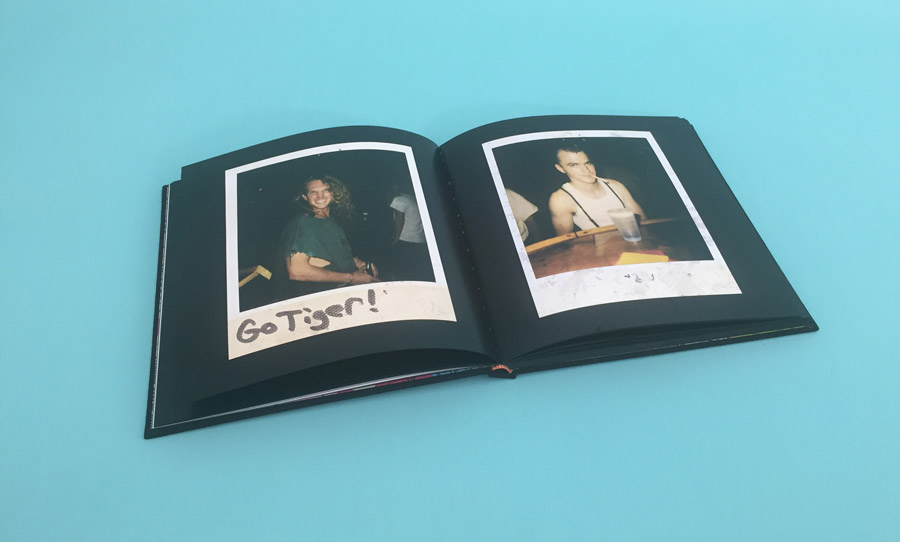

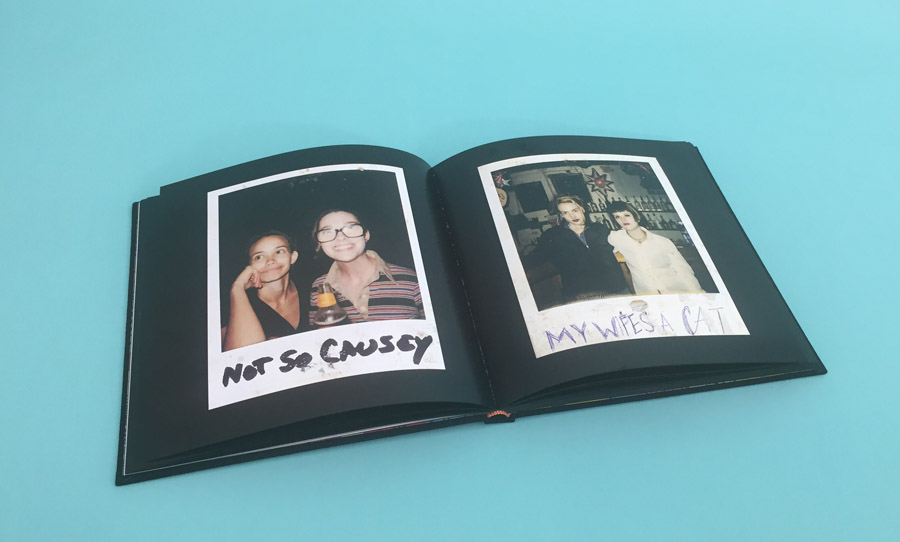

Yet, when you dive into the collection of Polaroids laid out in Bill Bryson’s All Of Us Are Now: Snapshots From A Rock Club, you’re left with the overwhelming sense that this could be your own favourite live music haunt, your own home town, and the memories yours.

All Of Us Are Now is a pictorial journey through the countercultural hub of Gainesville, Florida. At the centre of that hub was The Covered Dish.

The Covered Dish: This was the venue that Bryson ran throughout the Bill Clinton years: 1992 – 2000. And though it was only a generation ago, the way that we consume recorded and live music has utterly transformed.

Yet, at the time that Bryson was running the Dish, youth culture’s relationship with the music industry was also in a state of flux. As he mentions in the book’s introduction, “MTV was at the height of its musical influence” – but even cable TV’s deepening of pop and rock music diversity was nothing compared to today’s infinitesimal splintering caused by the internet.

Bryson adds, “Lollapalooza was pushing ‘alternative’ culture into the mainstream” – but this event was still an outlier, whereas today, you could argue that the oversized festival circuit has almost reached saturation point.

This was a time where mid-sized, local venues like the Dish were a crucible of raw talent – a place where an artist could scale the heights of artistic expression, or a punter could plumb the depths of debauchery. Often, the boundary between artist and audience was nonexistent, or roles were reversed. As Bryson puts it, “Music clubs operated as hubs where this energy coalesced.”

After Bryson’s introductory remarks, there’s a further prologue from Jim Stacy (of La Brea Stompers and Big Top). He paints a generally dire picture of low (let’s face it, zero) budget touring in the States at the time.

Upon arriving at The Covered Dish though, the mood lightens, and he expands on how Bryson and his staff embodied the finest of Southern hospitality: “The crew that ran, worked and populated the Dish took the task of throwing their entire scope of connections, knowledge and welcomeness with the utmost importance and sincerity.”

Examining the photos only serves to reinforce Stacy’s opinion. The shots in the book were taken at random by various staff members at the club, as well as some of the patrons. The faces, bleached by the Polaroid’s flash, shine back with intensity, drunkenness and in some cases, the simple clarity that goes hand-in-hand with childlike innocence (who says grown ups can’t have plain, simple fun).

Most of all, the warmth of acceptance is what greets you. It’s Southern hospitality in print.

Bryson must have taken great care in curating this selection (actually, if this was just a random selection, it’s even more profound). There are many portraits that depict a brotherly embrace, an intense moment of solitude, euphoric bliss and plain, shitfaced goofing off. All of them, however, have an unmistakable intimacy. If Bryson was trying to make you wish that you were there, he nailed it.

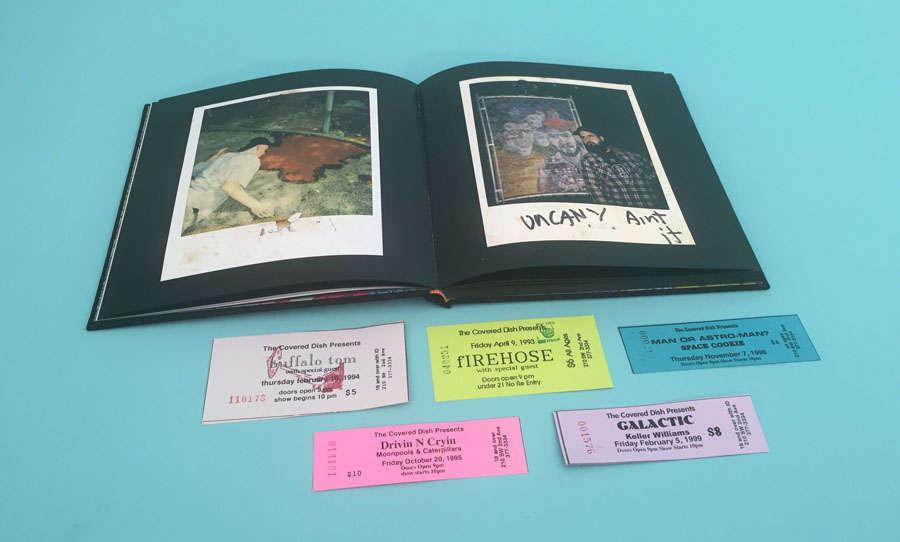

The book itself is something to behold, too. A hefty hardcover, the jacket a collage of the infamous Polaroid collection. Inside, you’re treated to ticket stubs from actual gigs that Bryson kept in a box alongside the photos.

The final few pages are dedicated to event posters that lay out the sheer diversity of the venue’s booking – Ani DiFranco, Less Than Jake, Manic Street Preachers, Smog, Green Day and possibly thousands more left it all on the stage of The Covered Dish.

The booked is rounded off by two epilogues. The first, by John Elderkin, adds the intriguing perspective of the employee. His portrait of the Dish underlines its banality on one hand: “No glamour there – just a cinder block, rectangular box in a parking lot shared with a delivery-only pizza joint in downtown Gainesville.”

On the other, though, despite its no-holds-barred reputation, he remarks on the boss’ incessant professionalism, “I remember that even in those slow nights, Bill came by the desk repeatedly with updated instructions and suggestions, always double-checking every detail. No nights off.”

The second is from Rick Stepp, a cultural anthropologist from the University of Florida. It provides valuable historical context about Gainesville as a community (so useful in fact that I wish it was at the start of the book) and how that community related to the music scene (which thrived on house parties, ably assisted by the tolerance of local neighbourhoods).

Critically, though, he reminds us that, “Buildings are buildings, despite the American tendency to fetishize the location … and obscure the people that really made it special. In the Dish’s case, it was all about the people.”

Which takes us back to the photographs. The people are at the centre of this story of beer-stained carpets, overflowing ashtrays and music that was probably way too loud. People who read All Of Us Are Now: Snapshots From A Rock Club should take heart – they can create their own Covered Dish, anywhere they want.

Visit the All Of Us Are Now website for more details.