2016 is a strange time. Rather than pirating, listeners are paying for music again. More than ever, music fans are streaming via ad-supported services like YouTube or subscribing to services like Apple Music or Spotify. But there’s another unlikely party that’s joined the fray.

Vinyl has returned. Echoing a wider global trend, Australian vinyl sales are booming. Vinyl as a physical format continues to grow while all others sink. Yes, the figures are impressive and media coverage is optimistic, but that’s just the surface.

There’s no doubt large scale vinyl sales are back, but what are the implications of the boom for musicians, fans and an ailing music industry?

ARIA stats show that, within Australia, overall music industry revenue was up 5% in 2015. It was the first upwards trend in annual musical wholesale figures since 2012. Going by ARIA’s previous figures, Australian vinyl sales more than doubled in 2014, increasing by a whopping total of 127 per cent.

The latest stats reveal that sales have dramatically jumped again by more than 30%. While 277,767 vinyl albums sold in Aussie stores in 2014, 374,097 were shifted in 2015. But to claim that these numbers tell the entire story would be misleading. The causes and longevity of the boom remain largely ambiguous.

Record stores have remained a traditional locus of music culture. Australia is no exception and it’s from the wisened disc peddlers running these smaller retailers that real insight into the vinyl boom can be gleaned.

Talking with independent record store owners across the country, we’ve uncovered the lowdown on the true drivers of Australia’s vinyl renaissance.

Shannon Logan is the owner of Jet Black Cat Music. She’s been selling music for around 11 years. Starting as a market stall selling CD’s, she’s spent the last six years running her brick and mortar store in Brisbane’s West End.

Logan runs a lean business, focusing mainly on new vinyl releases, but also stocking a small number of reissued albums released in the last 25 years.

“I would have gone into vinyl when I started but vinyl wasn’t as big a thing, it wasn’t an option at that time” she reflects. “But as time went on, maybe a year or a year and half before I went into being a shop, that’s when it started kicking in more.”

Shannon agrees that in recent years there’s been a heightened sense of value attributed to vinyl.

“I think people feel like there’s more value on a physical level. MP3’s are expensive,” she continues. “If it costs you $16 or $17 to buy a digital album compared to $30 to $35 if you buy a vinyl which includes a download, I think there’s way more value. On vinyl people listen to albums in full, as opposed to skipping through as they do on a CD, streaming or with MP3s.”

The explosion of vinyl in the last few years initially taxed pressing plants, leading to delays for smaller labels, distributors and artists. It’s led to claims from many who supported vinyl in its darkest days that they’ve been losing out. According to Logan, the delays which plagued pressing plants over the last few years are still a problem.

“An album loses traction if it comes out and the vinyl isn’t there on the day because the band or the pressing plant wasn’t organised,” she contends, but at least delays seem to subsiding; “it’s been a pretty good year this year, last year was worse, there’s been some more pressing plants opening.”

This said, Shannon believes a new challenge is emerging from shifting means through which artists are releasing music. “This year especially, artists are releasing records quite differently to how they did in the past,” she insists.

“Frank Ocean or Solange for example could drop an album this morning unannounced, but there’s no date for a physical release. There’s this adrenaline dump from when people hear about it online and that’s when they come to us looking for a copy. If there’s no date for [a] physical [release] we might lose a sale. People might want it later on, but when someone comes to us they’ve generally made an effort to get something specific, not to look around. They want ‘that’ record.”

2016 has also seen the trends for physical releases continuing to shift.

“Bands are not really doing CD’s now. They might do a limited run of vinyls that are numbered and they’ll have download or they’ll do cassettes. Cassettes are making a comeback,” Logan notes. “There’s not as much 12” or 7” singles anymore, it seems to be EPs and cassettes that have taken over. That’s definitely a shift that’s happened in the last year.”

Vinyl is everywhere. Online, you might pick up a new record while flicking through clothing websites like Urban Outfitters. Retailers like JB Hi-Fi are offering a wider range of vinyl and even grocers like Aldi have gotten in on the game. Shannon isn’t entirely happy with the encroachment of bigger retailers on the vinyl market.

“I think with JB Hi-Fi it’s frustrating because they’re selling you a record like Woolworths is selling you Juicy Fruit as you leave the store. For them it’s a tiny sale, whereas for as it’s the most important thing,” she levels. “But I think record labels are still looking out for independent shops, for example with the new Bon Iver record there’s a regular version and a deluxe indie exclusive version. JB Hi-Fi don’t have access to the deluxe version.”

“Record Store Day helps too, JB Hi-Fi can’t get a hold of those releases straight away,” she adds. “But at the same time labels are trying to survive. They’re trying to make sales and move units so they look to bigger retailers because they’re everywhere.”

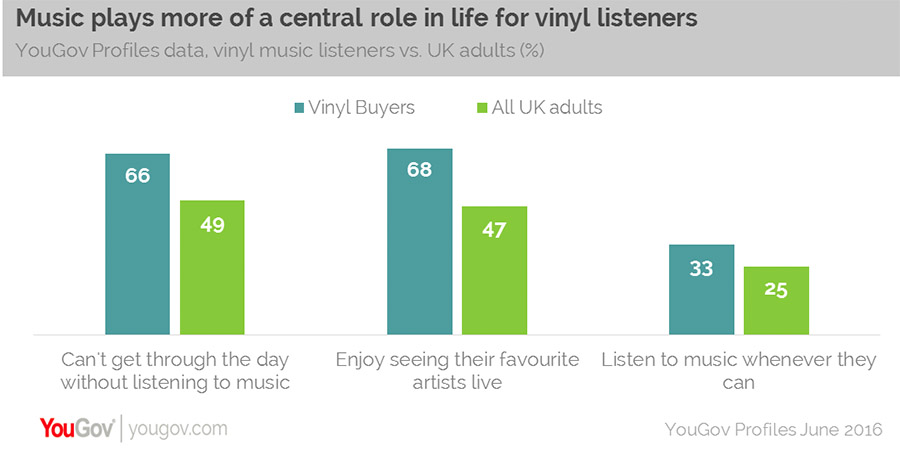

It’s still up in the air as to what demographic is leading the vinyl charge. A recent UK survey conducted via YouGov contended that it tended to be music obsessives between 45 and 54 who were driving the boom. Younger people surveyed between 18 and 24 were less interested, preferring t-shirts when it came to band merchandise.

Neilson has recently collected figures suggest something completely different. According to additional information the market research firm provided Digital Music News, it’s millennials who are driving sales. They’re 60% more likely to buy vinyl records than the general population, according to the dataset.

Shannon is not sold on either study. She disagrees with the notion that there is some form of ‘typical customer’ brought in by the boom. “Guys always buy more records than girls sure, but in terms of age it’s anywhere between 20 to 55,” she shares.

The Brisbane local also believes streaming is helping vinyl sales.

“Streaming is beneficial because, while it might be a minority of the people who listen to something on Spotify or Apple Music or whatever, some get to a point where they go: ‘I listen to this so often I can’t not buy it. I need to have it!’ And they say it when they come in! The fact that they’re telling me this when they come in says a lot.

“They’re the people that allow shops like this to keep going. They’re not regular buyers, but they’re the people who are coming in.”

Store owner Blake Budak has been selling vinyl, CDs and vintage clothing at Canberra’s Landspeed Records for 22 years. “There’s definitely been resurgence, but vinyl has never truly gone away,” he muses.

“When we started we were selling records and we’re still selling records. In that time the nature of the types of records and customers has changed. In the late ‘90s and early 2000s there was the big techno and DJ boom. That died off about the same time that the contemporary vinyl boom started to kick in around about 2008. From then on vinyl sales have progressively increased.”

Like his Brisbane counterpart the veteran shopkeep doesn’t discern a particular demographic as championing sales. This said, there’s certainly a difference between generations.

“It’s a real mix. Our vinyl customers are from 16 to 60 years old,” he adds.“On the younger end of the spectrum its people who’ve never embraced the physical format before. Vinyl is their first physical form. Others are CD customers we didn’t see for a few years who’ve now returned as vinyl customers.”

“The other sort of customer is older people who got rid of their turntable and vinyls years ago who are now missing it,” he says with mirth. “They’re buying albums saying ‘I used to own this 30-40 years ago!’”

Despite all this, the very way people use records might also be changing.

“People buy them as collectibles. People have listened to the album on Spotify or YouTube and they come and buy the album, but don’t even own a record player,” Blake adds with a slightly bemused tone. “Instagram posting of pictures of vinyl is huge. There are people with vinyl-focused accounts who have insane amounts of followers.”

It could be the cosier climate of Canberra, but Blake has little issue with bigger retailers getting in on the game.

“We actually do quite well having a JB Hi-Fi near us,” he surprisingly revealed.

“If people go in there looking for something they don’t stock they then come to us. Sometimes the store suggests people come here, they’re good in that regard. We consciously try to have things they’re not going to stock.”

It’s still the heavyweight international acts who are dominating sales. “The biggest albums of the last years are the biggest sellers on vinyl; Arctic Monkeys, Daft Punk and things like that,” he continues. “Even things we wouldn’t have stocked a couple of years ago like Taylor Swift, we’ve gotten in it and it just keeps on selling and selling and selling.”

Although in his view, it’s also helped out local artists.

“Then you get your Australian releases that do really well, like Royal Headache, they sell well but only on vinyl.”

Regrettably but not surprisingly, delays are still a problem in the Canberra store.

“It still happens with everything, some labels and some bands seem to be organised enough to have vinyl released, but for so many things it’s out months later. People move on to other things so quickly now.”

Nic Warnock co-owner of Repressed Records in Newtown, Sydney also runs independent label R.I.P. Society. Nic’s store traces a twisted lineage. Beginning as a suburban second hand vinyl and CD store in Parramatta and later in Penrith, the store began dabbling in more obscure music when retailers like JB Hi-Fi opened up.

“[Niche records] were the strength that we had. It was what other record stores in NSW weren’t doing. We decided to take a huge risk to move into the city and it worked,” Nic explains. The store now stocks new releases alongside its collection of second hand CD’s, records, books and DVDs.

Nic agrees that his store has benefited from a boom in vinyl in the last three years.

“There is a larger audience for it. I think it’s predominately people who would buy music on any format, they just don’t have the luxury of buying on the CD format anymore,” he shares.

But while Nic welcomes the boost in revenue, he isn’t afraid to issue some stronger opinions on the negative aspects of vinyl’s resurgence. As proprietor of a record store he is particularly concerned of the impact it is having on Australia’s underground network of artists, labels and fans. In his view, the truth about the vinyl revival has been distorted in the media and in some regards even farcical.

“There’s no doubt that the vinyl boom is real, but I think some of the statistics and the way it’s talked about are untrue,” he pointedly remarks. “[The idea of a ‘vinyl boom’] forgets the fact that vinyl has had a life in all these other areas; dance music, hip hop, punk and garage. What it has been is the major record labels catching up to the idea that people want vinyl.”

“People have been asking for things on vinyl but [the majors] haven’t been able to facilitate it for so long. Now that they’re doing it, they’re going overly gung-ho and re-issuing everything that’s ever existed in the most impractical and expensive ways,” he exclaims. “There’s more product to buy now so of course there’s going to be more sales.”

He’s worried that the increased output from major labels and “careerist” artists has upset a delicate status quo of those who have traditionally supported the format.

“There’s been a tradition of particular realms of musicians releasing music on vinyl and a network of distributors, independent labels and stores that create a community. Now people are doing it without any understanding of these links and they’re facilitating it badly.”

He’s also worried that increased demand for bigger releases on vinyl, while making things more profitable for record stores, might be hurting their ability to promote smaller Australian artists.

“Unfortunately independent music is becoming less visible, with labels doing everything on record, even re-issuing albums from the late ‘90s and early 2000s which may never have been released on vinyl at the time, bigger artists are taking precedence,” he laments.

“They’re making money for independent stores which sees them take over from what would traditionally be visible. You only have so many hours in the day and so much energy. Where a Beaches record may have been in some stores is now, I don’t know, something like a New Found Glory record. But I don’t think anyone is talking about this.”

Nic also expresses concern that the figures aren’t indicative of all the music that’s selling on record.

“All these figures they’ve collected don’t take the whole picture into account,” he expands. “We’ve never reported our sales statistics anywhere and we don’t use the industry standard retail cataloguing system because a bunch of what we’re selling isn’t in there. We get so much stuff from labels, artists and smaller distributors there’s no point. We’re not getting in the latest Kasey Chambers.”

Indeed, many of Australia’s record stores who have supported vinyl since its darkest days are unwilling to pay the hefty overheads of ARIA membership.

Although admittedly, Nic has noticed a trend of increased vinyl output in the underground music scene.

“Even DIY bands are putting out more vinyl,” he states with a more upbeat inflection. “People share that information, more people feel confident with the process.”

But delays are still an issue. “Pressing delays can get clogged up. When things like Beatles reissues come out they take over an entire plant. What have been craft industries are dealing with a new group of clients with bigger and more frequent pressing runs.”

Unlike Shannon, Nic takes a critical stance on events like Record Store Day.

“It’s major label imperialism over what is the culture and tradition of independent record stores,” he warns. “Record Store Day is majors trying to cash in on that good feeling and admirable cause of the independent store. They’re putting things into these stores that ignore the DIY spirit. They ignored them for so long, but now they want to use these avenues. They have all the rights to this amazing music, they just don’t know what to do with it!”

Nic agreed with his peers that there was a broad clientele brought in by increased interest in vinyl.

“People are going back to vinyl that used to buy it, big music fans who probably bought records in their 20s then bought CDs and are now buying records again. They’re glad to see vinyl coming back, but if it wasn’t available they’d probably still be buying on CD,” he notes.

“Another new audience is people who are probably getting to that post-university phase of having an actual income, people who are buying tip of the underground sort of things like Kurt Vile. It’s cool because it gets them into other things in the same tradition.”

He also thinks the interest in vinyl could be a reaction to the overwhelming clutter of music available online.

“People are finding that online there are so many voices and sources of music, there’s no particular authority. There’s so much noise and information. It’s difficult for people to figure out what’s real and what’s worth their time,” he theorises.

“Everyone has a surface knowledge about most music, but it’s more limited in scope. The underground is becoming invisible. People are using us now more so than 5 years ago.”

Vinyl revival is a phenomenon many are still trying to understand. The physical medium for music has been changing with surprising frequency for the last 150 years. Even sheet music sales were usurped by Edison cylinders, piano rolls and shellac records.

Spurred by growing demand for the album format in the 60s, vinyl’s heyday was slowly eroded by the portability of cassettes and the utility of CDs. These formats have in turn given way to digital.

They may be slow to recede into obscurity, but rarely do these technologies rebound. This is what makes vinyl so remarkable. The benefits of CDs, tapes and MP3’s have subsided while the warm fidelity of vinyl has endured the test of time and even taken on new significance.

Vinyl makes a liberating promise: an escape from an overcrowded, web-mediated reality. Yet a revolution in listening seems unlikely.

While vinyl may be upsetting the autonomy of some independent stores in terms of what music they promote, it seems like the boom will continue. However, while vinyl continues to yield impressive figures it pales beside some 11,317,489 albums ARIA noted as being sold in CD format in 2015.

While vinyl netted an impressive $8,910,933 in 2015 according to ARIA, it’s dwarfed by $207,597,476 which came through digital channels. For the industry at large it’s more of a silver lining than saving grace.

CD dominance may not be the case for much longer. In the IFPI’s 2015 report Warner Music CEO Stu Bergen noted that in Norway, the global leaders when it comes to streaming , half of Warner’s physical sales were from vinyl. In the land of our Nordic neighbours, record numbers of independent stores are continuing to crop up. Australia’s vinyl boom might still be catching up.

Vinyl comforts us with a link to the yesteryears of the music world, but CDs and digital albums continue to flag in a downward spiral. A reassuring takeaway is that there’s a network of passionate music fans and obsessives who will be supporting artists by buying physical music in whatever dominant format is at hand.

In equal measure, an unprecedented access to music has only seemed to amplify the need for the expertise of independent record stores, at least within their traditional spheres of influence.

The vinyl phenomenon is an economic model of supply and demand. This can especially be seen in the increased commercial product relating to vinyl, with Australian companies such as Rockit Record Players emerging out of the woodwork, even buying into the influx of new collectors by offering ‘Get Started’ style bundles.

Eventually the market will find equilibrium and stabilise. What goes up must come down. Furthermore, the rapid evolutions of the manner in which artists release music begs the question of whether the small victory of vinyl is faced with the greater demise of the physical format.

Vinyl’s return is truly remarkable, but despite a seductive lattice of media and industry triumphalism, there’s concerning elements to the vinyl revival. In the eyes of members of the Australia’s musical community like Nic Warnock there’s a greater need to shed light on what’s going on behind the scenes.

With the increased revenue, major labels have been granted greater power to dictate what these smaller retailers are stocking, the revenue from vinyl sales may be shifting away from independent artists. Fad or not, there is a material need for a greater understanding of the vinyl trend. There is much that remains contentious or unknown.

In the age of unprecedented consumer choice, vinyl caters perfectly to listener and fan. It seems that for every veteran returning to the format, there’s another newcomer discovering music for the first time.

Behind the scenes though, there are winners, losers and no shortage of industry politics.

The lack of consensus between just three of the hundreds of independent store owners operating throughout Australia on matters like the patronage of major labels, the relationship of smaller stores with larger retailers and the very nature of the boom shows that opinion is far from unified.

Just as our three music fanatics turned business owners could be expected to fail in reaching consensus over the top album of 2016, so too do they disagree on the significance of the vinyl phenomena. Far from a loaded conflict, the insights provided create verdant grounds for healthy discussion while the full story of the vinyl’s prolific return continues to unfold.