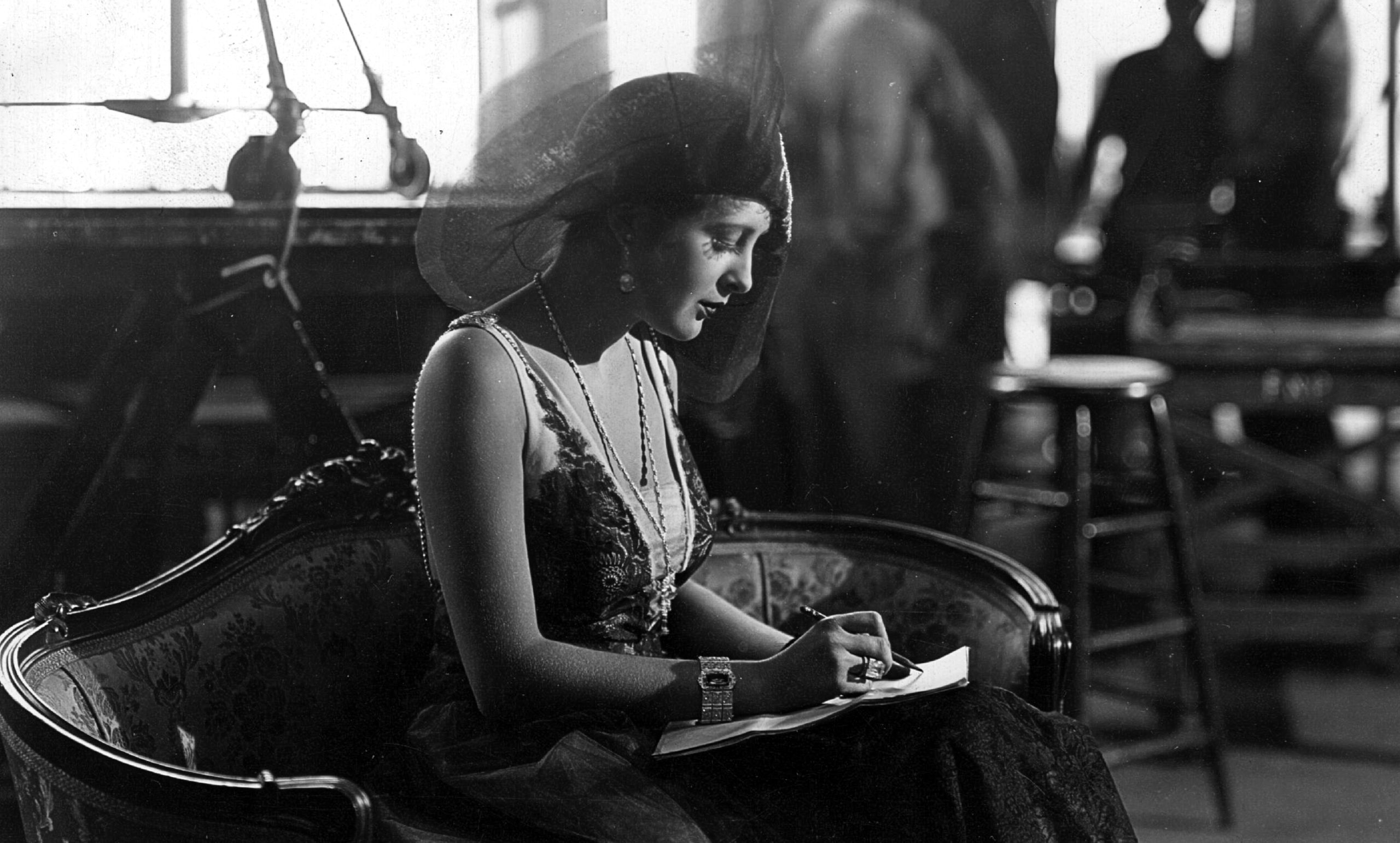

Everyone knows the swinging, swooning voice that belongs to Billie Holiday. But the life of the jazz legend was filled with more than song.

Billie Holiday was a firey, foul-mouthed revolutionary, who never sacrificed her integrity. The jazz legend, who was nicknamed ‘Lady Day’ by Lester Young, created hauntingly beautiful songs that have transcended time, retaining relevancy long beyond her death.

Though we know Billie Holiday’s voice as one that redefined jazz, her voice also heralded an anti-racist movement throughout the ’40s and fought for survival against the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. She should be revered as the musical genius, activist and trailblazer she was. Read on as we dive deep into the life and legacy of this icon of 20th-century music.

A voice to redefine jazz

When Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan) was born in 1915, the pop music world — as we know it — was still in a primitive state. However, by the time Holiday turned pro in the early 1930s, American music had been entirely reshaped by technology. Electrical recordings, microphones and radio were the ultimate complements to talents like Holiday.

By traditional measures, Billie Holiday didn’t have much of an instrument. When compared to the likes of Bessie Smith or Ella Fitzgerald, Holiday’s voice was small and slight. She possessed a midrange drawl that cracked and creaked when she sang, but the result was enchanting. She would sing in a hushed way, meandering around the beat while slyly elongating and truncating syllables.

Holiday admits she learned how to sing by listening to Louis Armstrong. In her autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues (1956) she says “it was the first time I’d ever heard anybody sing without using words”. In fact, if you play Armstrong and Holiday’s version of Yours and Mine side by side, you can hear how she mimics his swing rhythm and phrasing.

When Holiday sang, she would command attention not with forcefulness, but with reluctance. She sang behind a confidential hum, her vocals revealing only hints of pain, infatuation, stoicism, giddiness and defence. They were enticing enough to invite speculation but mysterious enough to keep the listener wondering: what were her secrets? It was an irresistible concept.

That signature shrewd and subtle vocal phrasing that is so important to blues and jazz music was boosted by the new technological tools on offer. Holiday didn’t have to belt out a song to reach the balcony of a vaudeville theatre; the microphone could amplify her murmurs to every corner of the hall. These dips and variations in her tone allowed an emotional intelligence to be expressed through song, which was uncommon in previous waves of music.

It was this subdued approach to singing that was a landmark change, influencing not only jazz singing but instrumentals, pop singing, theatre and film scores. Holidays vocal phrasing inspired a number of notable artists – among them is Frank Sinatra, who never shied away from expressing the huge debt he owes to Holiday.

In 1944, Holiday offered Sinatra advice on his singing: “I told him certain notes at the end he could bend”. He was enchanted by her recording of I Wished on the Moon and credited his mastering of ‘musical seduction’ to Holiday’s minute vocal shading and teasing. Sinatra said in 1958 “It is Billie Holiday…who was and still remains the greatest single musical influence on me“.

Despite all the praise Billie Holiday receives for her vocals, she is rarely recognised as a musical genius and pioneer. She was the first to prove the emotional power of soft sounds and incorporating them into her work. From rhythm to tempo, Holiday was understating jazz long before Miles Davis considered sticking a mute in his horn.

Strange Fruit: A protest anthem

Holiday has a wide array of work credited to her name. She played traditional feminine roles in torch songs such as Don’t Explain and My Man, where she is the bruised diva, subject to unrequited love at the hands of apathetic men. But Holiday’s singing could offer much more than that.

Her vocals could be haunting. They were saturated with feeling. The intricacies of her rhythm, her phrasing and her softness boasted a spirit of resilience. Billie Holiday had a voice that could capture emotional density: fear, bravery, despair and coolness. It was in Holiday’s hands, that a torch ballad could become a protest song.

New York City. 1939. Billie Holiday stands on stage and sings a song that becomes an anthem.

Strange Fruit was a lament against lynching. It described black bodies hanging from trees like native Southern fruit. The poplar trees she sings of are imbued with a history of racial trauma and racial violence. Holiday granted the song a slow tempo to do justice to a poem rich in imagery. Holiday didn’t just sing Strange Fruit. She inhabited it, earning the recording a place in history.

Immediately after this performance, Billie Holiday received her first threat from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

Michele Smith, owner of Billie Holiday’s estate, told The Guardian:

“She did not make all the best choices. But you have to understand why she was a certain way. As well as her childhood trauma, she wasn’t allowed to go to restaurants, to use restrooms, because she wasn’t treated as a full human”.

Billie Holiday’s narcotics addiction stemmed from the childhood and racial trauma she carried. She was influenced by partners and friends, particularly in her marriage to Jimmy Monroe in the early ’40s. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics waged a relentless campaign against Holiday.

Agents used her addiction as an excuse to target her. An FBI memo quoting a source from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics even states: “Because of the importance of Holiday, it has been the policy of this bureau to discredit individuals of this calibre using narcotics.”

In May 1947 Holiday was ordered not to sing Strange Fruit at a concert in Philadelphia. She refused. By no coincidence, that night Billie Holiday was raided by federal agents in her hotel room. She was later arrested and sentenced to a year in prison on drug possession charges.

Billie Holiday was vilified, politicised and targeted. She was a wealthy, openly bisexual black woman who spoke about sex, race and violence in the way we speak about them today. Her outspoken nature, and determination to continue singing Strange Fruit saw her permanently banned from performing in certain venues, yet she never compromised.

Holiday sang Strange Fruit in 1939 and then every night of her life for 20 years. She admitted that performing the song “took all the strength out of me… it’s emotionally draining. When we performed it live we always did it as the last song. You can’t do anything else after that.”

The fate of Holiday when compared to artists like her contemporary Frank Sinatra can be seen as a parable about race in 20th century America. Holiday was an adored cult artist who was prevented from reaching stardom in her lifetime.

She had been banned from performing in venues that served alcohol, and on her death bed had only 70 cents in her bank account. She died at 44, while under police guard in hospital. Sinatra, in complete contrast, outlived his musical hero by 39 years. He released some of the most lauded albums ever, was honoured by Presidents and died a multimillionaire.

Legacy

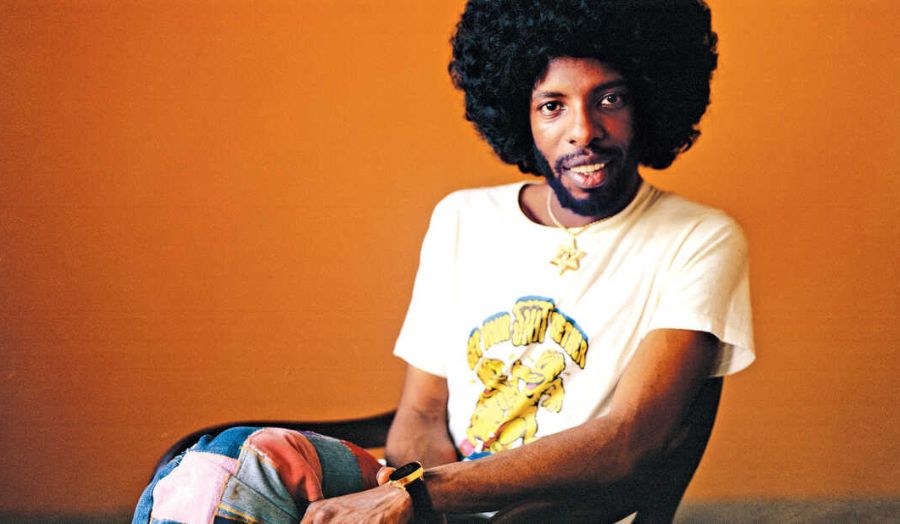

Against all odds, Holiday created an incredible legacy for herself, both as a jazz musician and a civil rights activist. Strange Fruit is one of the most powerful protest songs of all time and has continued to be covered and sampled to this day. Notable renditions of the song include those by Nina Simone, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Lou Rawls and Kanye West.

With the return of Black Lives Matter to national headlines, Strange Fruit took on startling new relevance. In the first six months of 2020, Holidays 1939 recording was streamed more than 2 million times according to the Rolling Stone Music Charts.

Billie Holiday’s life has been adapted into a number of documentaries, the most memorable of them is BILLIE (2019) by Linda Lipnack Kuehl, who pieced together Holiday’s life through a series of over 200 interviews between 1971 and 2017. Among the interviewed were jazz pianists Count Basie and Charles Mingus, singer John Hammond, drummer Jo Jones, actress Sylvia Syms, a number of friends, psychiatrists and federal agents. It received overwhelmingly positive reviews.

During and since her time, no jazz artist has come close to matching the emotional intensity and allure of Billie Holiday. This is why her legacy has endured. Michele Smith summed it up best when she told The Guardian: ” — She was a fighter. And, as an icon, she has survived”.