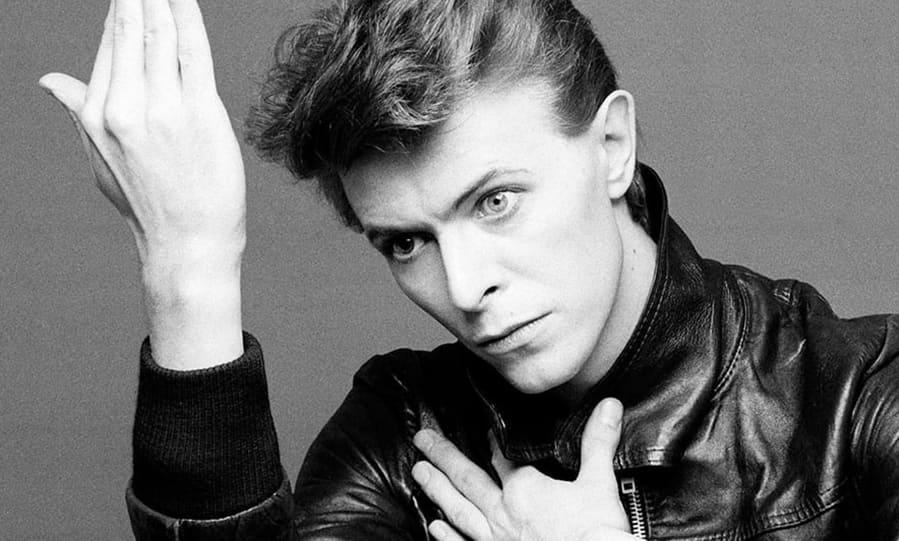

For his 12th studio album, David Bowie escaped the hedonistic L.A music scene and set up camp in a West Berlin studio to record one of his most ambitious and iconic works. Here’s how Heroes came together.

The late seventies were a pivotal time for music. Disco was dominating the charts and punk rock was giving the finger to arena giants. It was, however, a time of change and little by little, experimental studio processes and the forward-thinking use of electronic instruments were creeping their way onto the airwaves – and Heroes, David Bowie’s twelfth album, was a prime example of this.

At the time, Bowie had enjoyed a stream of success with the last decade bearing numerous chart-topping hits. However, feeling overwhelmed by the heady L.A scene – something he later labelled “A vile piss pot” – he pursued refuge and inspiration in West Berlin.

Heroes, Bowie’s 12th studio album, was the second in his ‘Berlin Trilogy’, a series of albums defined by their experimentation and ambient textures – courtesy of Brian Eno and the creative production style of Tony Visconti. Released in October 1977 by RCA Records, the album was the only one of the trio recorded entirely in Berlin, its sound reflecting the unique studio setting.

A Bleak Antidote

1970s West Berlin was a concrete jungle, still bearing war scars and cut through the seams by the Berlin Wall. But it was a hub for a new wave of musical experimentation. Krautrock bands such as Tangerine Dream, Neu! and Harmonia were using electronics like never before, reinventing the sound of rock music.

Bowie relocated to Berlin in 1977 and began detoxing from cocaine addiction, meanwhile immersing himself in the local art scene and synth-based, Euro-expressionist music. The title of the album was a nod to Hero, a song from Neu!’s album ’75, the band’s guitarist Michael Rother having been asked to play on the record. Played in a typical ‘motorik’ style the track V2 Schneider, refers to the Kraftwerk member Florian Schneider.

Heroes was recorded at Hansa Studios, a ballroom of the Weimer era that once was home to glamorous Nazi shindigs. The war had not been kind to the venue and in the 70s it still wore bulletholes on its external pillars and bricked-over windows. A vacant lot sprawled out behind it, which was home to a few gypsy caravans.

The studio was roughly 400 metres from the Berlin wall and the windows that still featured a view peered over at menacing armed guards in barbed-wire wrapped turrets. The wall, which was erected to stop East Berliners fleeing, watched over a no man’s land, called lovingly by locals ‘the death strip’. In fact, just months before Bowie began recording, an 18-year-old who attempted a courageous escape was fatally stopped by a flock of bullets.

Visconti recalled in an interview with the BBC: “Every afternoon I’d sit down at that desk and see three Russian Red Guards looking at us with binoculars, with their Sten guns over their shoulders… everything said we shouldn’t be making a record here.”

This bleak scene was just what David Bowie wanted: miles away from rock ‘n’ roll excesses and cliches, he was able to clear his mind to create something truly meaningful.

Writing for Heroes

By 1977, Bowie had a competent team of musicians who he had been counting on for much of the last decade. The instrumental side of Heroes featured Carlos Alamar on guitar, Dennis David on drums and George Murry on bass, a trio that Visconti asserts were ‘jam experts’.

“All three were amazing musicians. You’d just throw a few chord changes at them and they’d run with it.”

Most of the songs on Heroes started with Bowie giving his band a handful of chords and loose ideas to jam on; he knew that within half an hour his masterful disciples would form solid backing tracks. He would then extend and rework these ideas, as Visconti remembers: “Carlos might come up with the germ of a part, and then Bowie would help him elaborate, but once the two of them began exchanging ideas back and forth, you’d get amazing stuff.”

Different sections were developed in this almost improvisational manner, with no one knowing at the time what would be a verse or chorus or bridge. The songs organically evolved as more instruments were overdubbed and Bowie, treating the musicians and producer as a ‘committee, worked with their feedback and suggestions.

These backing tracks were the foundations of each song and Bowie used the mood and the feeling to inspire his melodies and lyrics, which would often come weeks or even months later.

In 1976, Iggy Pop toured with David Bowie for his Station to Station tour, before moving with him to Berlin in a quest to boost productivity and sober up. It was here that Bowie helped him to write and produce The Idiot and Lust for Life.

Iggy learned through Bowie the importance of work ethic and, in turn, Bowie picked up some interesting vocal techniques from the erratic punk. Iggy Pop was a proprietor of improvised lyrics, believing the raw sounds that came out in the moment of recording were the purest representation of emotion.

A lyrically frustrated Bowie used this technique for the album’s title track…

After Visconti met jazz singer Antonia Mass in a Berlin nightclub, he was immediately impressed by her voice and invited her to contribute backing vocals for Beauty and the Beast. During the vocal takes for Heroes, Bowie asked the couple to take a stroll so he could concentrate. Meandering near the looming wall, they shared what they thought would be a secret kiss.

“We went for a walk after David asked us to leave him for a few hours so he could finish the lyrics (to Heroes). As we walked in front of the Berlin Wall, which was very close to Hansa, we stopped and kissed,” remembers Visconti.

Bowie had been gazing out of the window at the time and was inspired by the show of romance amidst the spartan backdrop, and the couples’ moment was immortalised in the lyrics:

“I can remember

Standing

By the wall

And the guns

Shot above our heads

And we kissed

As though nothing could fall.”

Hi-fi for Heroes

As experimental as it was recording in a studio on the frontline of the cold war, Visconti had no shortage of tricks up his sleeve for the production of the album. One of his main weapons was the large hall in Hansa. In this space, he captured all of the natural reverb he could in order to “take the studio home for mixing”.

He was the proprietor of Neumann U-87 microphones, often using multiple at a time to capture not just vocals but instruments as well as the space of the Hansa hall. He said in an interview with Sound on Sound: “When I have a big room, I use that room’s sound, and we had an 87 in there that picked up all the ambience — the 87 is my Swiss Army Knife microphone, I use it for everything. Sometimes, I’d try to use two mics, but again it was sheer luxury to have two tracks for ambience.”

Visconti used Hansa’s 24 track Neve console to track the sessions. As many of the songs employed dense instrumentation and numerous microphones, he was required to mix on the go, so he could bounce the tracks down to free up space. The drums were recorded with up to nine microphones, including two overheads, three toms, kicks, snares, as well as numerous room mics to pick up the natural reverb of the Hansa hall. ‘Submixing’ allowed for the drums to fit on six tracks, leaving precious real estate for other instruments.

As the rhythm tracks were the basis for the songs, Visconti and Bowie made the decision to record effects straight onto the tape, rather than manipulating the recordings, later on, a method that was rather the opposite of standard technique.

An example was the use of tape flanging on George Murry’s bass; the effect was seen as integral to creating the “overall feeling” of the instrumentation. These rhythm tracks were recorded in just over two days, which gave them a sense of spontaneity.

A large component of Heroes’ unique sound is credited to the input of Brian Eno who since leaving Roxy Music in the early 70s had embarked on a quest involving many collaborations and experimentations.

Eno brought with him a ‘suitcase synthesiser’ – an EMS Synthi – which he would crouch over during live recording, meddling with the unit’s joy-stick and oscillator banks. Bowie and Eno had worked on ambient synth sounds since the first ‘Berlin album’, Low, and Heroes further built upon these early developments.

Moss Garden evokes a peaceful setting, ironically at odds with the stark Berlin setting. The track heavily features Eno’s synths, which weave in and out of a Japanese Kyoto, plucked by Bowie. Another unique tone was created for the album’s title track with a low-frequency oscillator and noise filter creating the characteristic chattering sound.

Strange Techniques and Secret Weapons

Heroes also had a secret weapon: King Crimson’s guitar virtuoso Robert Fripp. Known for his calculated and measured approach, Fripp produced ethereal and otherworldly sounds (one of his techniques was developed alongside Eno, eventually being coined ‘Frippertronics’).

Fripp played guitar over three tracks for the song, soloing over a rhythm section that he was hearing for the first time. It is rumoured that he completed all of the takes for the album in six hours, further adding to the spontaneity of the album. Fripp’s Les Paul ran through Eno’s EMS Synthi and then into the Neve comsole. He used measurements on the floor to indicate the optimum for the feedback of each note, for example, ‘A’ at 4 feet at ‘G’ at three and a half, meanwhile Eno altering the tone via his suitcase synth. By dancing over these taped lines on the studio floor he tamed the unhinged sound into celestial bliss.

In addition to piano and vocals, Bowie also contributed sax melodies, as heard on Neuköln, as well as the heavily Krautrock influenced V2 Schneider. He also played a primitive ARP Selina string synth, which Visconti later stated: “we thought this was the bees knees but it’s actually a really cheesy sound”.

They also used brass sounds from a Chamberlain (a precursor of the Mellotron) to further incorporate an orchestral feel to the album. However, the nature of these early synthesisers was that they sounded less like what they were emulating and more something strange in their own right, a characteristic Bowie and Visconti were more than happy to work with: “It was definitely written as a trumpet part, but it sounds more like a weedy little violin patch,” Visconti remembered about the album’s title track. “Still, we liked it in the end. We just said ‘Oh, that’ll do,’ because it sounded weird.”

With the same philosophy, an empty tape reel was used as a cowbell after the right pitch was found by bending it out of shape. It was recorded from 15 feet with an SM87 used to capture Hansa’s reverb. Notoriously impatient in the studio, Bowie was more than happy to adapt, using these unorthodox instruments rather than waiting for a brass player or a cowbell to appear.

Perhaps the most groundbreaking recording technique amongst these novel ideas was Visconti’s unusual methods for capturing Bowie’s vocals. Taking full advantage of the large spaces at Hansa, the producer used three microphones to capture vocal takes, one close, one at 15 feet and one at 20 feet. The first mic was often compressed and relatively dry, the second and third however used gates that would only open only after a certain volume limit was passed. Adjusting these gates, Visconti was able to capture Bowie’s vocals with a dynamic and ever-evolving reverb. The setup also encouraged a particular performance from Bowie, the close microphone allowed him to be intimate, however, to activate the third microphone he would have project across the hall, picking up all of the unique sonic characteristics.

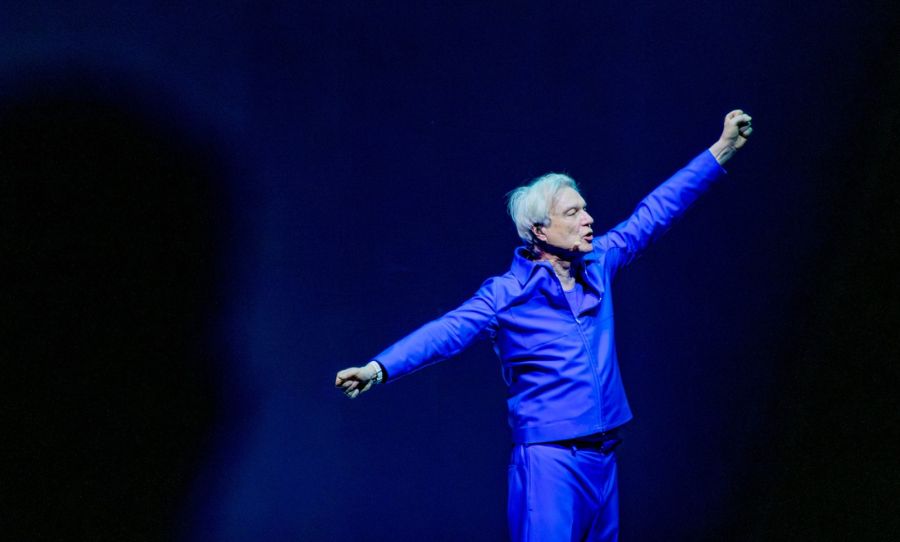

Heroes was not an instant commercial success like many of David Bowie’s albums, both before and after. However the unusual experimentation elevated the album to classic cult-like status, and the title track is forever a favourite among Bowie fans (and arguably one of his best vocal performance of his career).

The excellence of the album cannot be credited without mentioning the supergroup-like combination of producer and artists, Brian Eno, Robert Fripp and Tony Visconti and of course the bleak yet charismatic setting in Berlin, which acted as a melting pot for experimental ideas.