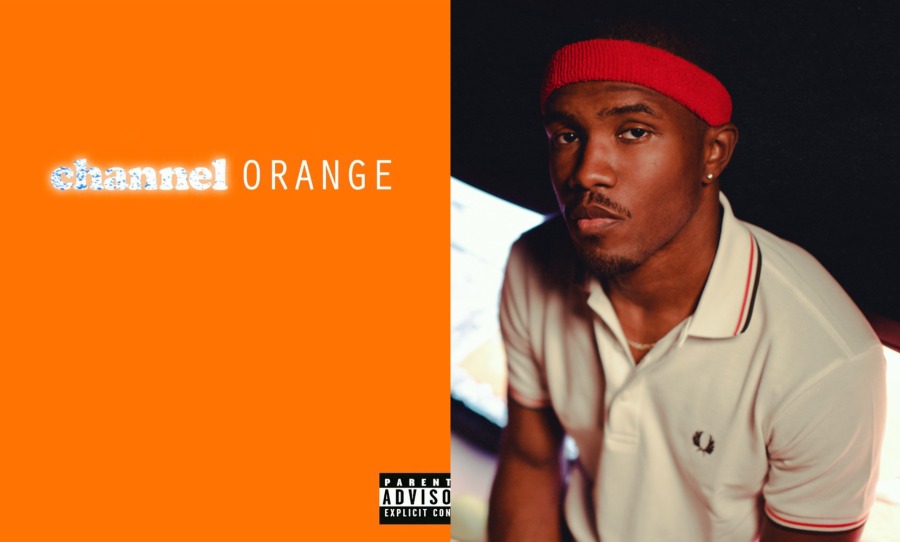

More than a decade on from its release, we’re taking a look back at Frank Ocean’s seminal, near-mythical debut studio album, Channel Orange.

When Frank Ocean dropped his debut studio album on July 10, 2012, he unwittingly changed the landscape of both modern R&B and music more broadly, in ways that are still felt today. Perhaps the term ‘unwittingly’ is misnomer, though, since the longevity of the reclusive musician’s Channel Orange seems — with the hindsight of more than a decade — almost meticulously predetermined.

With only a self-released mixtape to his name in 2011’s Nostalgia, Ultra, Ocean didn’t have much to prove on Channel Orange, which made its overnight, star-making success all the more revelatory upon its release. Commercial metrics aside — the album garnered Ocean his first Grammy nod and ascended to the top of the Billboard charts — Channel Orange is more a story of a game-changer shaking up the scene by the sheer force of creative vision.

With Channel Orange, Ocean crystallised himself as a touchstone of a musical cohort that both preceded and followed, from the Odd Future alum’s Earl Sweatshirt-assisted Super Rich Kids to the lyrical intimacy of Thinkin’ Bout You later emulated by SZA and Steve Lacy. With Ocean’s headlining Coachella performance on the way and a potential third album in the works, we’re taking a look back at why, 11 years on, Channel Orange matters.

Lyrical vignettes

Perhaps the most notable throughline on Channel Orange is Ocean’s overarching narrative. Though it defies a singular concept — the tracklist traces moments of unrequited love, undeserved wealth and more — it’s nonetheless tethered to a particular time and place. Each song offers a distinct vignette populated by characters, from the suicidal, affluent teen of Super Rich Kids to the Cleopatra-turned-stripper of Pyramids.

On Crack Rock, Ocean tells the story of a drug addict in “the middle of Arkansas”, while Lost recounts a drug mule caught-up in the lavishness of her jet-setting profession. Episodic scenes like this culminate until Channel Orange reads like something of an odyssey, coalesced by each character’s yearning for something more. This third-person approach — later seen on Forrest Gump and Monks — has the effect of collectivising the human experience.

“It’s about the stories,” Ocean said in a 2012 interview with Spin. “If I write 14 stories that I love, then the next step is to get the environment of music around it to best envelop the story.” Channel Orange’s goal in this way is only underpinned by its sonics (more on that later), but Ocean’s narrative lyricism alone feels both personal and universal, with each character’s song-length scenes part of the broader blockbuster that is Channel Orange.

Channel surfing

If Channel Orange’s lyricism helps listeners see his elaborate story, then its throughline sound effects help them hear it. Equally as episodic as Ocean’s narratives is the ambient noises he uses to punctuate them, beginning — fittingly enough — with the white noise fuzz of a television booting up on album opener Start. That track also samples the hum of a PlayStation switching on, and the beginning audio of the 90s video game Street Fighter II.

From there, the album remains dotted with sounds usually reserved for an afternoon in front of the telly. The interlude Fertilizer, for instance, may as well be a jingle straight from a 70s commercial, with its catchy soundbites and static frequency, as if Ocean is changing stations between tracks. The click of a remote is heard consistently, as is tape-recorded dialogue from Forrest Gump on its namesake track, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas on Lost.

By the album’s end, the TV-centric audio asides of Channel Orange feel much the same as a couch-bound session of channel surfing, with each new station or song switching on a different lyrical screenplay. The effect is to soundtrack the album’s stories with the precision of a filmmaker. “I like the anonymity that directors can have about their films,” Ocean told The New York Times. “Even though it’s my voice, I’m a storyteller.”

Pyramids

Nowhere is the combination of Ocean’s story-like lyrics and ambient sonics more masterful than on Pyramids, the nine-minute magnum opus so cinematic it should be reviewed by Roger Ebert. Both a smorgasbord board of experimental sounds and a brief history of Ancient Egypt, reincarnation and adultery, Pyramids serves as Channel Orange’s vital midpoint, in terms of album runtime and overall concept.

Achieving a lyrical feat worthy of its length, Pyramids draws a direct line from the dishonour brought upon Cleopatra as Mark Antony’s mistress to that likewise experienced by modern day sex workers. For the first half of that story, Ocean employs bombastic synths befitting of Cleopatra’s Egyptian status, using the double-meaning of a “cheetah on the loose” to recount the Queen’s betrayal and subsequent “tremble” of chandeliers as she meets “her doom.”

Flash-forward through a minute-long interlude — helped along by a groovier R&B beat switch — and we arrive several thousand years into the future, “wak[ing] up to a girl” who Ocean instructs to “call her Cleopatra.” The stilettoed woman, Ocean explains, is “headed to the pyramid,” presumably a stand-in for a brothel. Pyramids accomplishes a full-circle allegory, providing Channel Orange’s narrative axis by equating Giza to a strip club, and so chronicling the intergenerational mistreatment of Black women. All achieved in under ten minutes, and with a guitar solo courtesy of none other than John Mayer.

“4 summers ago, I met somebody”

Any look back on Channel Orange would be remiss not to mention its creative impetus, which Ocean groundbreakingly laid bare in an open letter posted to Tumblr six days ahead of the album’s release. Across a few-hundred words, Ocean recounted one of Channel Orange’s main inspirations, a 19-year-old man he’d met “4 summers ago.” The confession that Ocean’s first love was of the same sex was near-unprecedented in hip-hop. And so the game was changed.

On July 4, 2012, Frank Ocean shared an open-letter on Tumblr called “thank you’s.”

The letter was intended to be released in the liner notes of 'Channel Orange,' but seeing certain speculation made Frank want to get his own words out there. And his words were powerful ones. pic.twitter.com/6m8RnBqjMV

— Pigeons & Planes (@PigsAndPlans) July 4, 2020

Setting aside the fact that Ocean’s coming out letter involved no corporate machinations — it’s a low-quality screenshot of TextEdit file clearly unedited by PR — it also provided insight into the tenderness of Channel Orange, as Ocean explains his intent to “create worlds that were rosier than mine.” The unrequitedness of his first romance echoes tenfold on the album, made all the more pioneering by the fact that it was gay love.

Ocean was compelled to release the letter amid speculation around Thinkin’ Bout You and Forrest Gump, both of which contained male pronouns. The subsequent essay shattered glass ceilings, not only recalling the sexual fluidity of the Bowie’s and the Mercury’s before him, but outlining a musical path later trodden by Harry Styles, Jaden Smith and more.

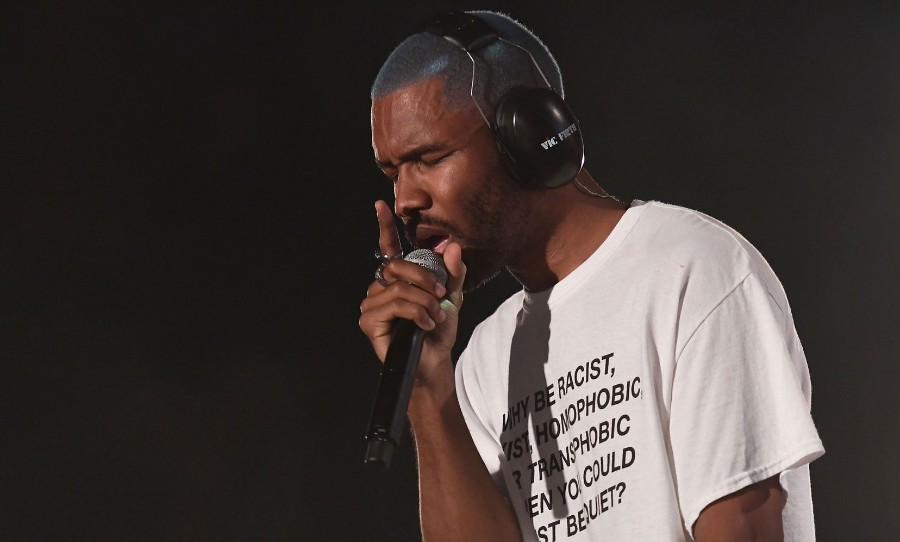

The musical recluse.

By and large, Ocean followed a traditional pop-leaning album rollout for Channel Orange, sharing a string of pre-release singles, undertaking press junkets and performing promotional sets at the Grammy Awards. This route, however, was almost completely abandoned following Channel Orange’s release, to the point where its successor, 2016’s Blonde arrived wholly without warning.

Since then, Ocean has become a bonafide recluse, rarely making appearances and speaking to the press about as often as a lunar eclipse. So withdrawn is the singer from public life that his annual interviews garner a level of hysteria reminiscent of The Beatles, and his drip-fed, cryptic releases spawn Reddit decodings and hundreds of articles preempting his next album.It’s a level of stardom that borders on the mythical. But, as we’ve learned from the musical genius that is Channel Orange, it’s undoubtedly well-deserved.

For more on Frank Ocean, head to Happy Mag’s take on everything we know about his next album here.