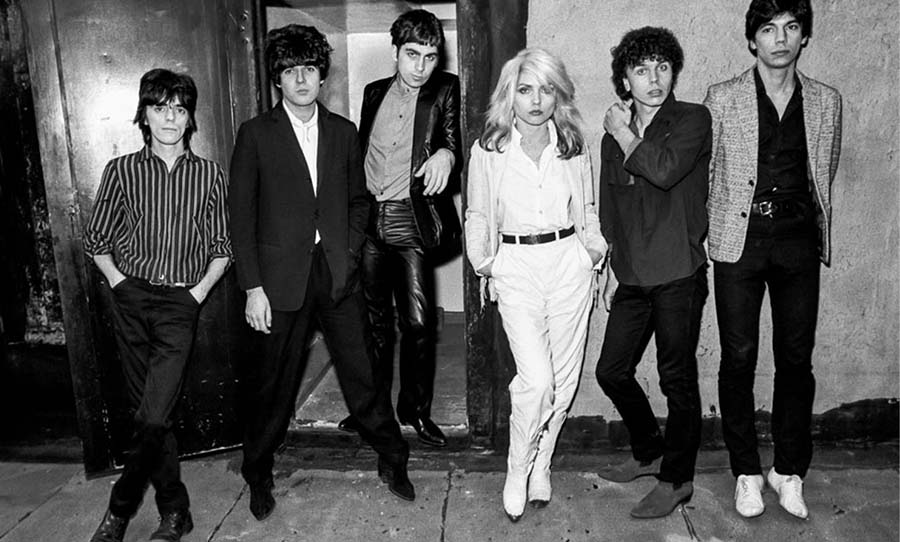

New York in the late 1970s was a colourful place. A place where the fringes of society festered and evolved into a creative stew, despite the fact that the city’s unemployment and crime rate were on a steady upward trend. In these dark corners, a committed punk and new-wave scene embraced the city’s rustique charm and rejected the poppier disco hits that dominated the airwaves.

Blondie was cut from this cloth and, in 1978, already had two albums under their studded belts: Blondie (1976) and Plastic Letters (1978), neither of which had received much recognition in their home country, aside from their small circle of punk associates. Their sound was punk at heart, but they were not afraid to experiment with different sounds and genres, however, to truly lift themselves out of the downtown grime, they knew they would have to do something very different.

What it took was the studio wizardry of an eccentric Australian producer and a shed-full of the latest and greatest state-of-the-art studio equipment.

Blondie’s ‘Heart of Glass’ marked a career turning point as they transitioned from punk to pop, pioneering groundbreaking studio techniques in the process.

Blondie never really expected to make it big; they assumed their fate was tied with the rest of New York’s outcasts, but in 1977, Chrysalis Records saw something special in the band. Debbie Harry had a formidable stage presence and wasn’t afraid to ‘go there’ lyrically, nor did she care for the men who thought her themes weren’t very ladylike. The band set themselves apart with their powerful songwriting ability, coaxing Chrysalis into spending a cool million bailing them out of their previous record deal.

The label recruited the Australian producer, Mike Chapman to work with the band. He had already established himself working with the likes of Suzie Quattro and Mud. Right away he saw that their creative juices and willingness to experiment had the potential to take them further than their peers. All they needed was a bit of a push.

Heart of Glass actually started its life as a loose funky jam, a demo the band dubbed, Once I Had a Love or, more simply, The Disco Song. Having recorded a rough take over 3 years prior, the band decided to blow the dust off the track and breath some new life into it.

“Heart of Glass was one of the first songs Blondie wrote, but it was years before we recorded it properly. We’d tried it as a ballad, as reggae, but it never quite worked. At that point, it had no title. We just called it ‘The Disco Song’,” recalled Debbie Harry in an interview with the Guardian.

The whole band had been listening to Kraftwerk at the time, which had them all inspired to add a little ‘electronic flavour’ into their creative process. Kraftwerk had spent the larger part of the decade experimenting with early synthesizers, effects, vocoders and drum machines and the band wanted in on the action.

Guitarist Christ Stein recalled in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, “We loved the idea. As a band, we had already been referencing the electronic-dance feel of Kraftwerk, which released Trans-Europe Express a year earlier. We felt that would be a move forward. But getting that sound back then was a mystery to all of us.”

That was until Chapman sourced some of the decades most groundbreaking electronic gizmos.

The first shiny new bit of gear was the Roland CR-78, one of the first drum machines ever built. The CR-78 was released earlier in 1978, making Heart of Glass one of the first songs to feature the new machine. It completely changed the direction of the track.

The CR-78 was originally created to accompany lone-wolf players, lounge musicians who couldn’t afford a drummer. It had settings to match, such as ‘Foxtrot’, ‘Tango’ and ‘Shuffle’, and the original wooden facia was designed to match a prospective jazz muso’s organ… smooth.

But Blondie didn’t play in lounges, they were rock musicians and soon found a different use for the machine. To form the basis of the song they started with a simple tempo click, combined with the ‘Mambo’ and ‘Beguine’ settings. Anyone who hits pies will know how difficult it can be to play along to drum machine, so drummer Clem Burke really had his work cut out for him keeping in time with the machine.

On top of the CR-78, Burke laid on the drums, but not just one take, oh no. Eight individual tracks for each piece of the kit, any small errors could be cut out of the tape on that track, otherwise Chapman would make him do it all over again.

“What I was asking Clem to do was close to enslavement, and he was ready to kill me,” recalled Chapman. Slowly the beat came together and I mean slowly – each step in this process was painstaking, taking hours to get a take that lined up with the machine.

Just getting the drums down took a week, but the result was that each instrument in the kit could be processed and EQ’d individually, resulting in a very punchy drum section that complimented the song’s electronic feel.

The next fancy bit of hardware was the Roland SH-5, a then-new space-age synthesizer and along with the classic Minimoog, these synths covered three tracks on Heart of Glass, adding in a very ‘Kraftwerkesque’ rhythm sound.

Keyboardist Jimmy Destri spent hours trying to work out how the new synthesizers worked, and eventually configured a method of syncronising the CR-78 with its synthesiser stablemate, the SH-5. The drum machine’s tempo setting was able to send a ‘trigger pulse’ to the warbling synth, creating a very functional albeit DIY sequencer, at a time when they weren’t widely available.“It was such a big deal just to get these two things in sync,” Destri recalled.

Another revolutionary bit of gear used during the sessions was the EMT 250s, the first digital reverb ever created. Packing in a powerful 16KB of RAM, the unit got hotter than a rocket and required three fans and a heat sink to cool it down. Heart of Glass was one of the first recorded examples of the unit and Chapman sourced two, after discovering the company while in Switzerland a year earlier.

“They gave the snare – drum – and later the vocal, more dimension and an electronic vibe,” Chapman remembered.

The EMT 250s is still sought after today for its warm modulation and because of its rarity, with only 250 ever produced. Also used on the ambience front was the trusty Roland RE-201 Space Echo. Chris Stein used an Ebow on his guitar, in combination with the RE-201’s built-in reverb and swirling tape delays to create textural effects.

With all of these hi-tech components, all that was needed was the swing of some choppy guitar, courtesy of Frank Infante’s Les Paul. And, of course, Debbie Harry’s unmistakable singing. Instead of her signature growling punk vocals, Harry utilised her higher register, laying down a catchy hook that subsequently immortalised the song. The vocal was double tracked, and a low octave was added for the chorus, giving the vocal lines a punchy undertone.

“Recording Debbie was a blessing, how often do you get to record a singer who is instantly identifiable… she represented New York,” lamented Chapman.

By the end of the sessions, the band was constantly arguing, fatigued by the hundreds of takes and tired with the tedious process. Recording with Chapman wasn’t always smooth. The man was a known perfectionist, bordering on obsessive-compulsive.

He pushed the band to record take after take. As a band who spent their formative years trying their best to sound unpolished, Blondie weren’t accustomed to such antics: their punk roots didn’t quite gell with Chapman’s nit-picking nuances. One idiosyncrasy was his apparent obsession with time; during sessions he would walk around with a stopwatch, timing each section before questioning and probing as to why it was all taking so long.

“Mike was a perfectionist and a real taskmaster, we weren’t used to playing things 50 times… the genius of Chapman was that it sounded spontaneous, but after playing the same part for an hour or two hours it didn’t feel very free-flowing at all,” recalled Chris Stein.

As the song began to take shape, no one, not even Mike Chapman expected it to be such a hit.

“I never had an inkling it would be such a big hit or become the song we’d be most remembered for. It’s very gratifying, ” Stein said in an interview with the Guardian.

It goes without saying, Heart of Glass was a massive success, it was the biggest single of their career and number one in 16 countries, launching the band into the stratosphere of international stardom. It captured the sound of New York at a pivotal moment and has gone on to provide the soundtrack to many films set at the time. The album Parallel Lines has sold over 20 million copies to this date.

After the release, Blondie played a kind-of farewell gig at their old stomping ground, CBGB; a farewell at least to their history of just being another punk band. The line sprawled all the way around the block and Blondie knew they definitely couldn’t come back, especially after hearing taunts like: “You’re disco album sucks!.”

For a band emboiled in punk, Heart of Glass did sound a bit like disco… and that didn’t sit very well for some. They were accused of selling out by many in their old community.“The Ramones went on about us “going disco”, but it was tongue-in-cheek. They were our friends,” recalled Stein.

Even if the track sounds a little poppy, a little disco, it’s there still exists an undercurrent of what Chapman coined “New York grime,” and the track is an undeniable testament to Blondie’s embrace of state-of-the-art technology and Mike Chapman’s studio wizardry.