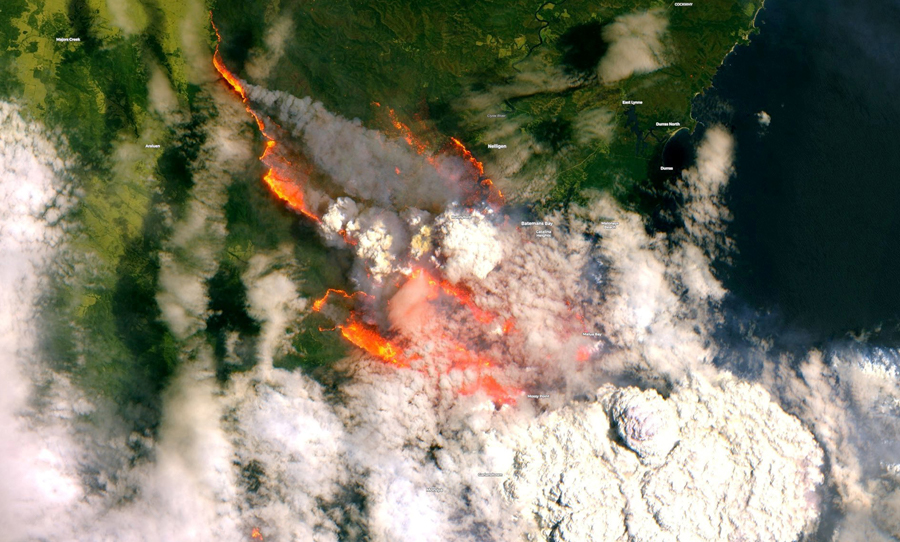

Last year, the Australian landscape was blazed by the worst recorded bushfires in history. Despite the fantastic efforts of firefighters and the surrounding communities, the impacts on the local environment were devastating.

One such animal that copped it hard was the green carpenter bee (Xylocopa aerata); a glistening, aesthetically-pleasing twinkle-sect that once thrived in numbers within the South Australian region.

The green carpenter bee is 2cm in length, making it one of the largest species of native bees in Australia.

The carpenter bee derives its tradie name from its natural ability to build its own home in Australian trees. This excavating technique differs greatly from other insects, who choose to instead reside in previously existing holes.

Although the green carpenter bee is no honey pollinator, many native Australian plants rely on its pollination for seed reproduction.

The green carpenter bee ain’t just pretty colours! The buzz-pollinating species transports the pollen out of the flowers of significant terrestrial fauna (such as guinea flowers, velvet bushes, Senna, fringe, chocolate and flax lilies), who become completely reliant on the psychedelic-looking insect.

Over the years, the green carpenter bee has been virtually wiped from the Australian environment, due mostly to bushfires. As the bees use deadwood (which burns quickly and easily!) for nesting, they are particularly susceptible to bushfires. They tunnel their nests into softwood that, once burnt, can take up to 30 years to grow large enough for the bees to utilise for shelter.

However, with the presence of Australian fires increasing at an alarming rate, it’s made it nearly impossible for the carpenter bee to survive. They were deemed officially extinct from the South Australian mainland in 1906, while the Black Friday fires in the beginnings of 1939 wiped the bees completely off the face of Victoria.

The green carpenter bee still exists in the western part of Kangaroo Island in South Australia, patches in NSW’s Great Dividing Range, and conservation areas around Sydney.

Scientists realised something really needed to be done to help these poor buggers out after the 2007 bushfires on Kangaroo Island virtually incinerated the entire Flinders Chase National Park.

“We bolstered the remaining population by providing nesting materials,” writes a group of research scientists on The Conversation.

“Since then, each year we’ve placed artificial nesting stalks in fire-affected areas where the bee still occurred. Almost 300 female carpenter bees have successfully used our stalks to raise their offspring.”

Just as hopes were looking up for the beautiful green carpenter bees, the 2020 Australian bushfires blanketed the nation and flogged the bees’ habitat almost beyond repair.

In the months following the catastrophic disaster, scientists have merged together to help build nesting stalks (with the ongoing support of the Kingscote Men’s Shed) in concentrated areas with decent floral holdings. Funds were raised through the Australian Entomological Society and the Wheen Bee Foundation.

The prevalence of fires and increased intensity throughout history, due in part to global warming, have made it difficult for much native Australian flora and fauna to survive.