The Beatles’ Tomorrow Never Knows was a feat of studio wizardry that, in 1966, had seldom been seen before. This is how it was made.

Lay down your mind, relax, and float downstream as we take a magical mystery tour through the wildly creative, and innovative engineering behind The Beatles’ Tomorrow Never Knows.

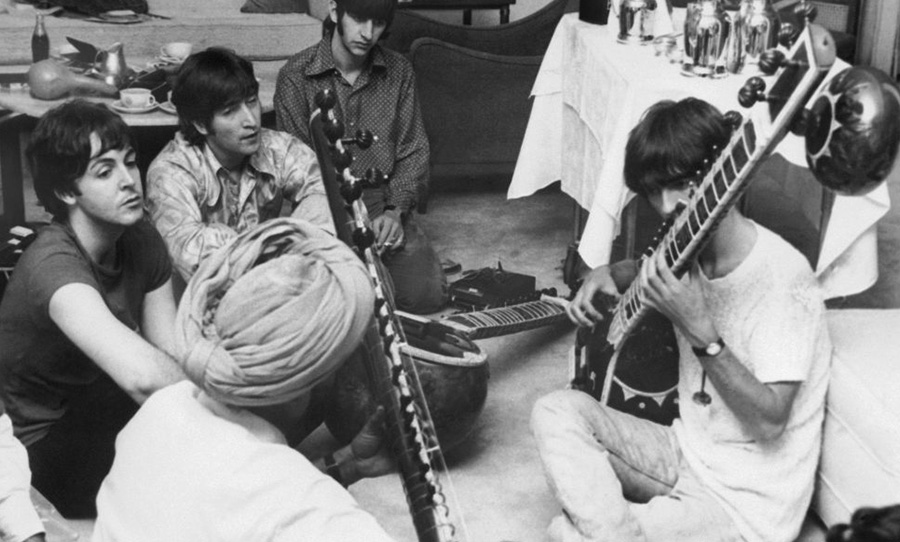

Released in 1966, the closing track to their seventh studio album Revolver, Tomorrow Never Knows exemplified the band’s burgeoning ability to use the studio as an instrument, weaving a psychedelic masterpiece that cleverly manages to combine Paul’s recent discovery of musique concrète, John’s interest in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, George’s desire to bring Eastern musical scales into the Western World, and Ringo’s constant, but by no means standard, drum patterns.

After their decisive early retirement from live performance in 1966, The Fab Four were unshackled from the pressures of writing songs to suit their live shows, and were for the first time able to take full advantage of the rapid advancements in studio techniques and technology, particularly the ability to manipulate tape.

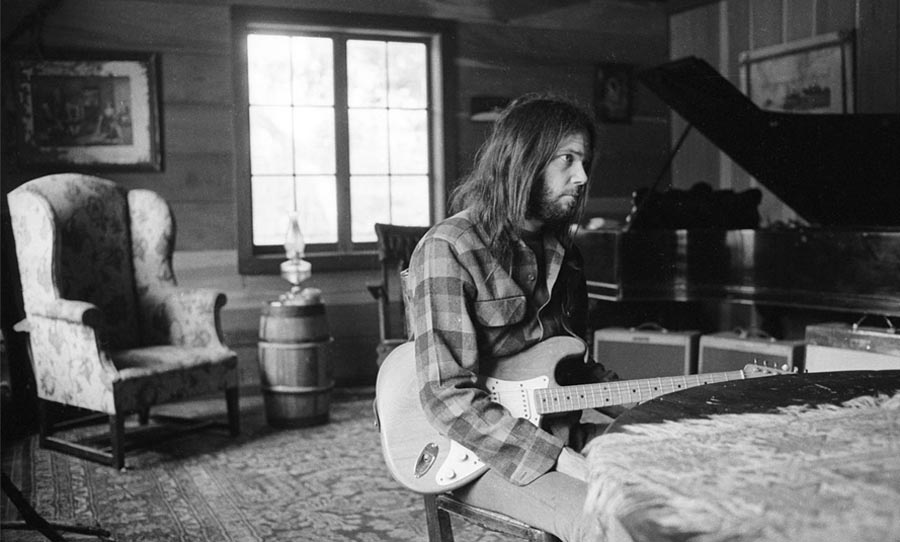

In anticipation of the recording sessions for Revolver, Paul was showing an increasing interest in the musique concrète movement, vocalising his particular admiration for Stockhausen’s Gesang Der Jünglinge for its use of tape saturation and looping effects.

He had discovered that by disabling the erase head of a tape recorder and then spooling a continuous loop of tape through the machine while recording, the tapes would constantly overdub themselves, creating this saturation effect he’d heard in Gesang Der Jünglinge.

Enamoured by the concept, Paul encouraged the others to create their own loops, and by the time it came to the first sessions for Revolver on April 6th 1966, the band had supplied George Martin with over 30 tape loops they’d created on their own in which they’d further manipulated by slowing down, speeding up, reversing, and saturating.

These loops would become the perfect backdrop to a song John had just written, then titled ‘Mark I’, which was a far departure from their previous material. It featured John earnestly chugging away on a single C chord, inspired by his recent acquisition of the book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead by Timothy Leary. The book contains the line: “Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream”.

Out of the 30 loops supplied to Martin, only 16 made the cut, each only lasting around 6 seconds.

Five loops that are most recognisable in the final mix are: a recording of McCartney’s laughter that was sped up to resemble the sound of seagulls, an orchestral chord of a B-flat major, a mellotron played on it’s famous flute setting, another mellotron on it’s string setting, alternating between a B-flat and C in 6/8 time, and a sitar playing a rising scalar phrase, recorded with heavy saturation, and sped up.

It’s also been speculated that a portion of McCartney’s fuzz-heavy guitar solo from Taxman was also used (slowed, reversed and pitched down) during the instrumental break.

What really makes the tape loops significant, though, is how they were woven together to produce the final mix.

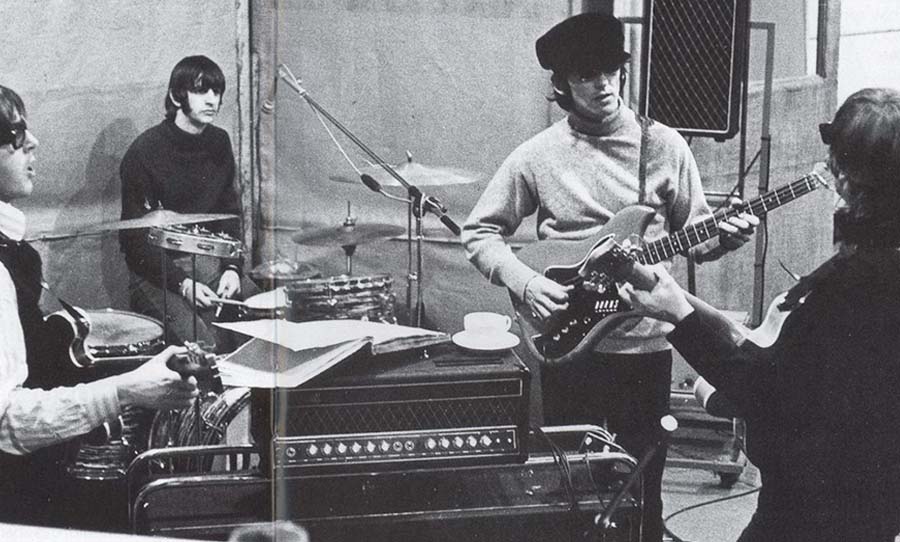

Five separate tape machines around the Abbey Road building were used to record the track. Each machine was controlled and monitored by an EMI technician, holding a single pencil or glass tumbler within their assigned piece of quarter-inch tape to maintain tension as they watched it pass through the capstan and past the playback head, endlessly repeating itself.

While the techs took to their post, the four lads from Liverpool took charge of the faders on the main console in Studio 3, while Martin varied the stereo panning, and the then 19-year-old engineer Geoff Emerick monitored the meters for levels as they recorded take after take, live to the master tape.

As Paul recalls, “We played the faders, and just before you could tell it was a loop, before it began to repeat a lot, I’d pull in one of the other faders, and so, using the other people, ‘You pull that in there,’ ‘You pull that in,’ we did a half random, half orchestrated playing of the things and recorded that to a track on the actual master tape, so that if we got a good one, that would be the solo. We played it through a few times and changed some of the tapes till we got what we thought was a real good one.”

George Martin further comments that Tomorrow Never Knows “is the one track, of all the songs The Beatles did, that could never be reproduced: it would be impossible to go back now and mix exactly the same thing: the ‘happening’ of the tape loops, inserted as we all swung off the levers on the faders willy-nilly, was a random event.”

After completing the recording, McCartney was eager to gauge the reaction of the band’s contemporaries, as he knew nothing like this had been attempted in popular music before. On the 2nd of May, he played the song to their friend Bob Dylan at the latter’s hotel suite in London; as the track started, Dylan said dismissively: “Oh, I get it. You don’t want to be cute anymore…”