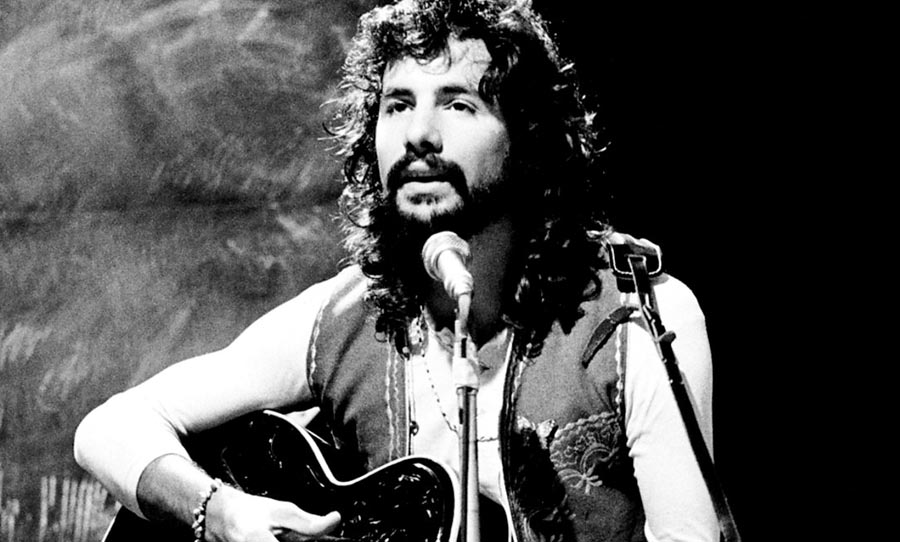

Cat Stevens was already recognised as a prodigious songwriting talent, but with Tea for the Tillerman, he elevated his art to a new level, with a fresh and simple approach.

By the time Cat Stevens (who was born Steven Georgiou) was ready to hit the studio for the Tea for the Tillerman sessions, the twenty-one-year-old had already survived a lifetime of tumult. A child of divorce, a schoolboy outsider and a survivor of a serious illness, Stevens managed to funnel these experiences into a single record.

Despite already being a star of some renown, Tea for the Tillerman was the effort that broke Stevens on a truly international stage. Except it didn’t sound like an effort at all. Gone were the lavish orchestrations of his earlier work, replaced with simplicity, strength and clarity of message—even if it contained the breadth of human experience.

Evolution in sound

Tea for the Tillerman was released in November 1970 and for many fans, it represented their first exposure to the young songwriter. The sound of the record was also emblematic of the folk revival, so it’s surprising to think that Stevens’ career could have taken a very different path.

Stevens’ garnered national attention in the U.K. with two albums released in 1967: Matthew & Son and New Masters. Both records were released on the Decca subsidiary, Deram. The records produced by Mike Hurst still had Stevens’ deep sense of lyricism, but this was somewhat diluted by rich orchestrations, which typified the sound of The Beach Boys and The Beatles.

His star as a pop artist was rising, but this was derailed in 1969 when he fell severely ill with tuberculosis. Unthinkably, he had to rest easy for a whole year, but this spell in convalescence helped Stevens rethink his approach to making records. He also studied religion and meditation and had a spiritual awakening that would inform his subsequent songcraft and approach to production. After his recuperation, Stevens was hardly in the mood to recreate the sound that had made him famous. He managed to get himself released from his contract at Deram and signed with Island Records.

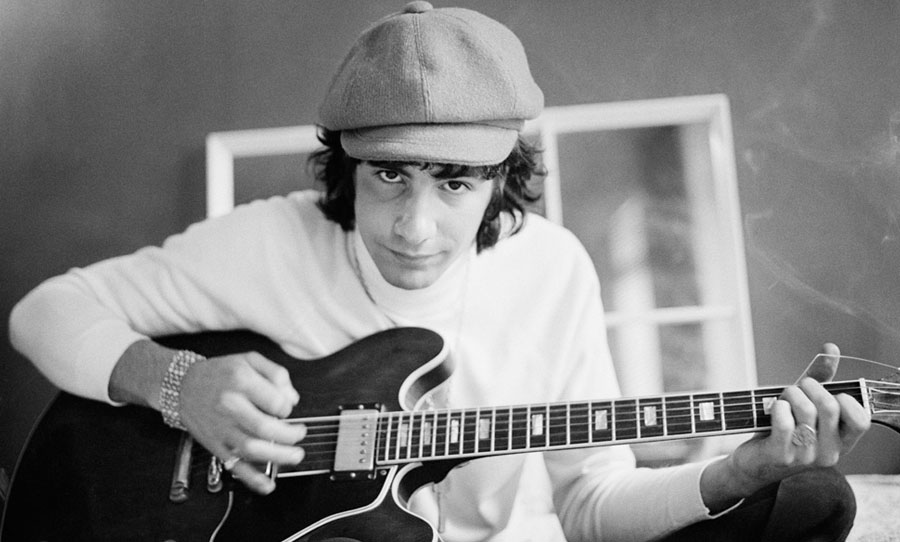

When he reemerged in 1970 with Mona Bone Jakon, a new Cat Stevens had arrived. The flamenco-inspired Lady D’Arbanville led the album and if that wasn’t enough of a departure, Stevens sardonically shed his former identity in track number three, Pop Star. Cat Stevens was making the record he wanted to and a factor in this success was his partnership with producer Paul Samwell-Smith and guitarist Alun Davies.

Going global

While this record, with an edgier folk-rock sound, made a splash in the States, the second album in this fertile year launched Cat Stevens into the stratosphere. Tea for the Tillerman was recorded in the months leading up to his twenty-second birthday at three studios across London: Morgan Studios, Island Studios and Olympic Studios.

The album contains some of his defining works such as Wild World, Father and Son and Where Do the Children Play. And while the album is free of the orchestral flourishes that marked his earlier work, it’s still incredibly sophisticated in its arrangement and production.

From the opening motifs of Where Do the Children Play? Stevens and his band mark out a simple musical path, with slow harmonic movements, demarcated by sonorous double bass thumps, with the bell-tones of the electric piano colouring the chords in the second verse. It’s all so subtle and serves to couch his voice in context, rather than distract from the lyrical content.

Simple yet experimental

Throughout the record, the palette of sounds remains relatively static: acoustic guitars, pianos and keys, bass, drums and vocals, which makes the experience all the more cohesive. It also serves to remind us that the album is a record of a moment in time—no excessive labouring—just a man with a message.

That’s not to say that Tea for the Tillerman is devoid of experimentation. Sad Lisa showcases a lush string arrangement compared to other tracks, while the final track on Side One, Miles from Nowhere features adventurous slapback delay (which could have been inspired by another famous release of that year). It continues on Side Two with But I Might Die Tonight, with some spacious reverb treatment on the backing vocals.

Tea for the Tillerman sold over three million copies in the U.S. alone and was the catalyst for a golden period of releases for Cat Stevens, with four more albums to follow on Island Records, including the equally commercially successful Teaser and the Firecat.

It’s remarkable to think that he would retire less than a decade after his seminal album after converting to Islam in 1977. Now, as Yusuf, he’s returned to a sound that affected so much of the world and his most recent release, The Laughing Apple, is spun from the same thread as Tea for the Tillerman.