With Nouvelle Vague, Richard Linklater reminds us why patience, conversation and time still matter in cinema.

Right now, there are a lot of movies out there that feel like they’re being made by committee, stress-tested, and watered down for franchise potential before a camera even rolls.

Which makes Richard Linklater, a filmmaker who still believes in people talking, time passing and ideas unfolding, feel strangely radical all over again.

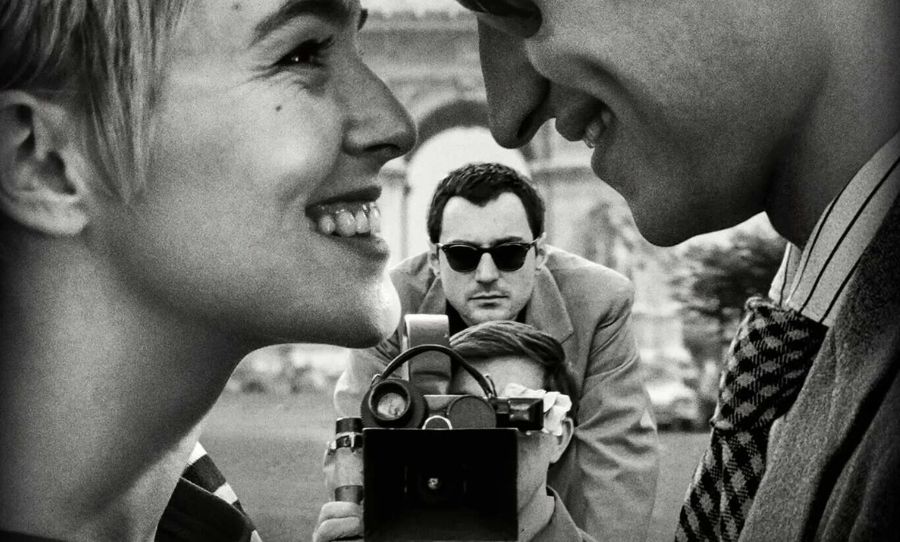

With Nouvelle Vague, his loving tribute to Jean-Luc Godard and the birth of the French New Wave, Linklater is celebrating the beauty of human creativity – the mess, the conversation, the moments that bring a film to life.

He’s looking backwards to move forwards, reminding us of a moment when filmmakers rejected polish, permission and predictability.

In doing so, he’s quietly pushing back against an industry that’s never felt more obsessed with speed and scale.

Linklater has always trusted time in a way few directors dare to. His films linger. They wander. They let characters ramble, contradict themselves, fall silent.

From the aimless poetry of Slacker and the sun-baked chaos of Dazed and Confused, to the deep emotional investment of the Before trilogy and the audacious 12-year experiment that was Boyhood, his work asks viewers to slow down and meet it halfway.

Nouveau Vague feels like a continuation of that belief system rather than a detour. By revisiting 1960s Paris and the restless minds that reshaped cinema, Linklater draws an unspoken parallel to now – another moment when the rules feel calcified and creativity is at risk of being smoothed into oblivion.

Back then, Godard and his peers blew up the system. Today, Linklater resists it by opting out.

That resistance feels sharper in a moment defined by AI scripts, digital performers and algorithm-driven storytelling. Linklater’s cinema, built on collaboration, conversation and trust, is stubbornly human. It’s messy, talky, occasionally indulgent – and that’s the point.

He doesn’t make films designed to be binged or franchised. He makes films that ask you to sit with them, to listen, to notice time passing.

In 2025, that kind of patience feels almost subversive – and maybe more necessary than ever.