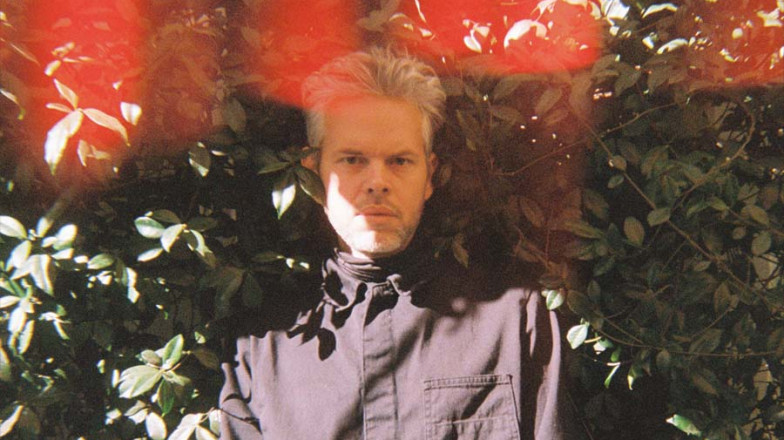

As Pnau, Empire of the Sun, and now Vlossom, Nick Littlemore is responsible for some of Australia’s most inventive dance music. But not even we expected his methods to be so bizarre and fantastical.

Nick Littlemore has an extraordinarily unique approach to his art, which is likely why he works best with another set of ears, whether they belong to his brother Sam in Pnau or Luke Steele in Empire of the Sun. He needs to be reined in, otherwise who knows what would come out?

With yet another Littlemore side project – Vlossom featuring Alistair Wright of Cloud Control – soaking the airwaves, we caught up with Nick over the phone to chat. From within the walls of his Los Angeles studio he revealed his most fundamental tools for music making, physical or otherwise.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 14. Order your copy here.

HAPPY: So you’re in your studio in LA?

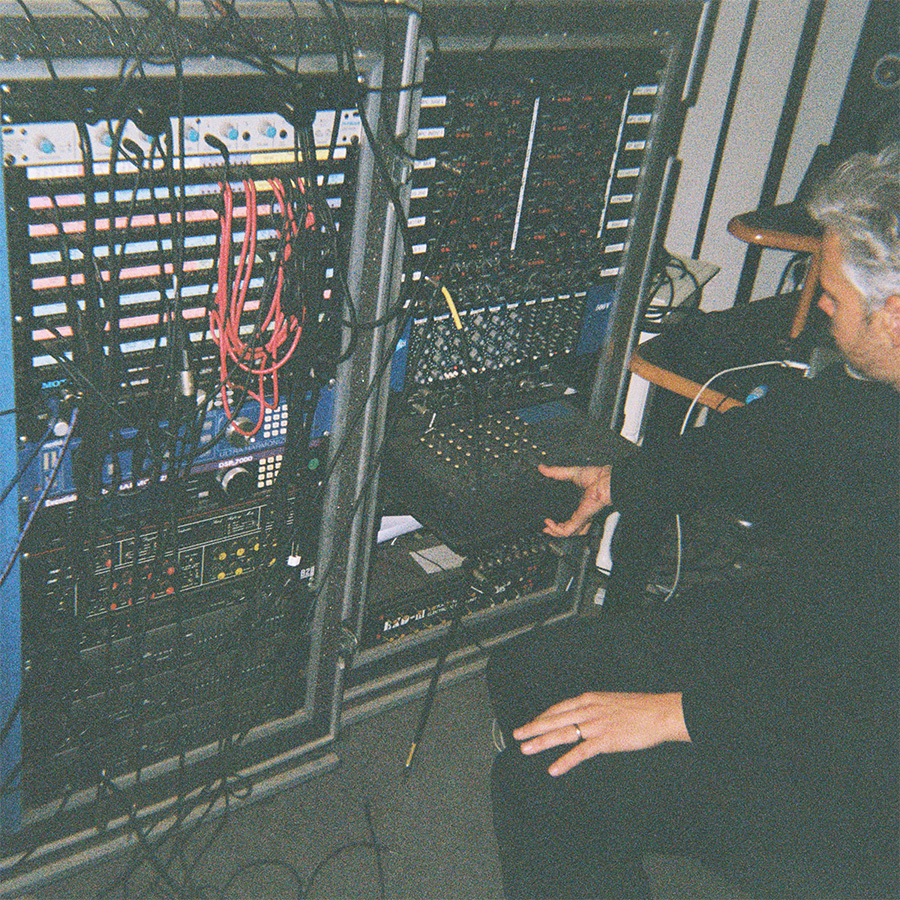

NICK: Yeah I’m in my home studio, which is in a one-car garage. It’s just full of gear, basically. As of right now I’m getting everything turned on, but there’s a few bits that are not quite working as nicely as they could.

HAPPY: Can you run me through some of it?

NICK: I’ve got quite a lot.

HAPPY: Let’s start in synth land, then.

NICK: The [Yamaha] CS-80 is definitely one of the main things. I got it in New York a while ago now and these are behemoths, they weigh about 220 pounds so it doesn’t get moved around much.

HAPPY: It doesn’t come on tour.

NICK: No, it doesn’t come on the road, which is unfortunately the nature of techno and any of the stuff we do. You couldn’t tour… I mean maybe you could, but you’d have to have a few techs on the road with you fixing things at all times. I know Elton [John] used to have two CS-80s on the road, but even he retired that.

HAPPY: What’s the challenge getting that sound on the road then? Do you use samples, or some kind of emulator?

NICK: It’s running track a lot of the time, sometimes we multi-track or multi-sample the instruments when we get a really special or unique sound that lends itself towards performance. But it takes forever, to be honest, and to do multi-samples that have expression, then you’re talking about multiple layers of each sound… it can take a lot of time away from the stuff which we really enjoy, which is more about creation. I don’t know, it’s a bit of a head fuck.

But having said that, on the Vlossom stuff, Doug [Wright], he’s Alister’s brother he’s very tech savvy. So he’s been resampling a lot of the parts that we’re giving him for the live performances and re-cutting them up, doing lots of crazy stuff. It’s really cool, but in Pnau we lock it in much more, it’s much less rock-dance and just dance dance, the swing and everything is so much more pertinent.

HAPPY: Of course. In terms of DAWS, are you someone who jumps between different DAWS for live tracking, arranging, et cetera, or is there a favourite?

NICK: I use Ableton for ideas, but because I’ve been using Pro Tools… actually, only about a year longer than Albeton. I was an early adopter of Ableton and used to play live a lot just straight out of Ableton. So I do love both of those systems but I find Pro Tools… just for the hours and hours of editing and tracking and something like the CS-80, it’s always a little out of tune. So the way we get around that is we, because it’s mono for the most part, we do like 12 to 24 layers of a single part and you get an nice overall, chorus-y, warm, fuzzy kind of sound that’s never quite on the note, but it’s enough.

HAPPY: That’s interesting.

NICK: It’s like a choir singing, it’s always a little under or above the note.

HAPPY: What’s your piano collection like?

NICK: I’ve got a Bechstein upright from 1890 which I got in London, I got it for a couple of hundred quid, a beautiful Bechstein in black. So I have that in my living room. I use it for ideas – I think I’ve recorded it maybe once or twice, to me it’s more about getting an idea. I mean, I record it on the phone and then generally I’ll email the phone recording to myself and then Melodyne parts, and then run it back through the CS-80 which has been retrofitted with MIDI. Then I’ve got another big polysynth which is the Rhodes Chroma, which I don’t use quite as much but it does have some really beautiful sounds in it.

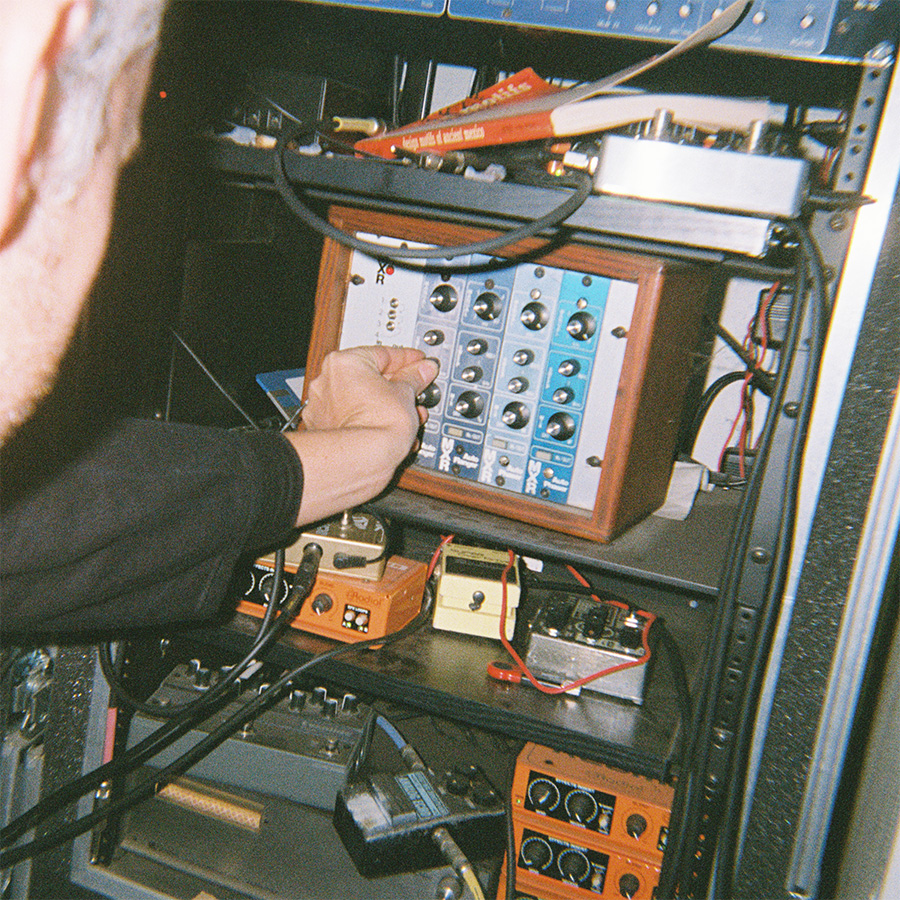

And then I’ve got a kind of elegant setup – I say elegant, that’s the wrong word, it’s so messy – I’ve got a setup of these monosynths, they’re called Kawai 100Fs. They’re originally Teisco which was a guitar, keyboard, and amp company from Japan, it was bought by Kawai and they came out as a Teisco 100F, which is one of the first synths I ever got. Then Kawai went on and made it – the Teisco one is rarer and it’s a little bit wilder but they’re fantastic sounding and very stable monosynths. So I’ve had them retrofitted with CV gates and connected to a little CV gate-to-MIDI, so I can control all four of them and play chords on these old, messed up monosynths. They’re kind of like MiniMoogs but these were a couple of hundred bucks.

HAPPY: I’ve never heard of those.

NICK: They’re not that common, but they sound so great, and even though they’re kind of rare, they’re never very expensive. They’re topped at around 800 bucks now, but you know I’ve been collecting these for… let’s just say quite a while. Maybe like 20 years.

HAPPY: And it’s taken you that long to get how many?

NICK: I’ve got eight of them now! But they just sound so great, you do see them at op shops or on Trading Post.

HAPPY: Sounds like something that sounds unique is more important to you than something that’s, you know, high end for the sake of it.

NICK: That’s really the driving force for us, we don’t have the obvious things in our studio like a Juno-106 or a [Korg] M1 or so many of the typical synths, I don’t have any of them basically. Well, we used to have an M1 downtown in the Pnau studio – Peter’s half of it. Here I try to have the weirder stuff which means that quite a few things have broken, which is quite annoying. But even with the broken stuff, if it turns on you can still get something out of it.

HAPPY: That’s true.

NICK: It’s when something doesn’t make any sound at all that it’s kind of a drag.

HAPPY: You said the piano is like mostly for ideas – are there any other really important idea stations for you? I heard that on a lot of the Pnau stuff an MPC is pretty important.

NICK: For me personally it’s the [E-mu] SP-1200, which I’ve had for a long time. For generating something quickly, that would be my go to. When I’m travelling it’s Ableton on the laptop because I can’t take the SP with me, but that’s my favourite piece of all the pieces, and other thing is with a sampler, of course, I can put all the other pieces inside the SP, make crazy sounds and then sequence them and pitch them around. I think the SP is… it’s not underrated because most heads know about it, but it is such a great tool for making, principally because it has a sequencer, you can easily pitch each sample, and it’s only very limited sample time so it’s really relying on your creativity to come up with something. And all these great records have been made on them. If those guys can do it, you know, they didn’t need anything else and that’s pretty exciting.

HAPPY: Various producers have studio rules that they live by, whether it’s something like always burning incense or it’s having no vocal booth so you can bounce off your singer face-to-face. Are there any studio practices that you have that you’ll never let go of?

NICK: No, I have a lot of practices, a lot of different techniques for approaching things, because I didn’t go to the Conservatorium, you know? I know a little bit around music but it’s more for me about how to get an idea out, whatever it can be. So I’m always building up and breaking down in different ways, but there are lots of different techniques that I use for unlocking ideas or creativity. And using both real world things, acoustic things, found sounds and things like that as well as digital things and digital generators. Using things like Melodyne in weird ways and tricking synths, like sending polyphonic parts to monophonic synths or turning an odd part that’s going through lots of delays into MIDI and then sending that back out to the synth and quantising… just fucking with the system a bit and rinsing stuff back and forth through the gear.

HAPPY: Doing all the stuff you’re not meant to do?

NICK: Yeah, kind of creating mistakes, like running towards things where the gear isn’t really designed to do that, but you can get some really interesting results from it. I think this is in the spirit of electronic music and always has been. Music has always been electronic since we’ve been able to hear it out of the speaker, so there’s always been some kind of element that was recreated or messed with, you know, depending on what amp it was going through, or speaker, or the room it was in. There’s so many variables and stuff, but lately I’ve been enjoying recording stuff comfortably in studios, mixing and then putting it on cassette, and then pitching it and sampling and then – say drums or something like that – then putting that back in the SP.

I just enjoy doing processing. I mean, it can be arduous and takes a long time but I think if something sounds different, if it has a unique sonic feeling to it, whether or not the audience picks up on it, they know. There’s some element to which it’s different and I think different is good. That’s not saying that everything different is good, but changing the artifacting of it… and that’s why I like these early pitch shifters which are very similar to the SP-1200 and the MPC’s 12-bit or 8-bit technology, it’s not quite speaking our language but it’s speaking a really cool version of it. As a result it leaves bits in and places other parts, different harmonics will shine in different samples… all that shit is really interesting to me. I never wanted to be verbatim, I’m not looking for a perfect, classical kind of recording.

HAPPY: Where’s the finish line for something like that? Because what you’ve just described, it could be a loop that goes on forever.

NICK: It’s a rabbit hole! You can just keep adding layers. I do have a side project called Two Leaves, which is my don’t-make-a-cent project, but I enjoy doing it because there’s even less rules. With the other projects there is a radio end game, or dance floor in some cases. But some things I just process. You know, you like something about it but it just doesn’t feel right so I run it through gear and degrade it, degrade it, and degrade it until it turns into something else. It’s kind of like cooking down a stew until it just becomes mush. Looks tasty though, I guess.

HAPPY: I was gonna ask about restrictions, but it sounds like there aren’t any absolute ‘nos’ that you apply.

NICK: Not really. In terms of the writing process I think it’s really important to be open to ideas and techniques, and half the battle for me is just convincing someone that I’m co-writing with to go down the rabbit hole a bit and try things they haven’t done before. I think it’s fun when you’re exploring, I think really good things can come when we don’t know, but when we’re enjoying ourselves and we’re exploring through the colour and the shapes of the sounds rather than being in a completely familiar place.

Having said that, I wasn’t someone that grew up playing guitar every night and having that approach to music, for me it’s about fucking with shit, you know? And computers would be my main instrument, right? Samplers, they’re not necessarily like keyboards and guitars. We all arrive at music in different ways and I think they’re all valid ways.

HAPPY: When you have these projects that are at a size, something like Pnau or Empire of the Sun, that many people would consider more than enough to occupy yourselves, what’s the catalyst for starting something different? Like Two Leaves or Vlossom.

NICK: Well Two Leaves was because I’ve been making things… I like to work, I like to make things all the time and as people have gotten older and have families and all that shit, I’m still here getting high and making weird shit. So I just want to start sharing it and putting it out. I’ve really enjoyed that process and making things with a different approach, and it feeds back into Empire or into Pnau, I might sample a little bit of something that I messed around with and that will end up being an Empire record or part of a Pnau record, or whatever. I like to make a lot because I think I’m not someone who could just sit down and write something that’s gonna be great, a single or whatever, it’s all about the exploration and every day I turn on all this gear and shit’s different. Today two of my Eventide’s aren’t working! Last time I turned them on, they were fine, and today my Publison’s working, which wasn’t working. So everything influences things in different ways, I think you’ve got to be there to catch the magic so I just do a lot of recording.

The Vlossom stuff was because I met Alister and he was such an enigma, things came together really quickly. Empire, initially it came together really, really quickly. I love new things, before they happen there’s so much promise for what could be and even when you’re entering the room of something like that, you just are more open and creatively explorative. And there’s a wilder thing; once things get going and maybe you had some success or whatever, you tend to go to where it’s familiar again, whatever that sound is. I like the newness of projects and it is putting some kind of limitations on each project, I guess. But overall there should be no essential things, every time it should be broken down in a different way.

HAPPY: Vlossom in particular this drug influence in the way it’s marketed and in the names of songs. What part have they played in your music?

NICK: Well I’m in California, so weed’s legal, I’m not breaking any laws. Alister and I had a shared love of entheogens when we got together, and plant medicine and that kind of approach to things and bringing that spirit into the studio, literally, has been really exciting. And I wanted to make that project different in some way, so hence a lot of the drums started off as a drummer and then went to cassette and then went to Ableton and then went to SP and then they sort of lived this whole life. Normally drums are really, really crisp – I mean they still come out crisp at the end through mixing – but we wanted to do something that felt like it had worn in. Even though it’s a brand new project, it feels like it had already lived.

HAPPY: I asked because everything you were saying about that no-wrong-answers, everything living a life approach… it seems very closely linked with hallucinogenic creativity.

NICK: Totally, totally. A huge thing for us with pretty much everything is that the first three minutes of playing something with someone and having them sing, even if it’s just the tiniest phrase or two little bits you cut up, it’s usually there, which I find really interesting. We do a lot of recording and a lot of improvising, we’ll get just a couple of chords and Luke and I will sing back and forth – we call it Idol but obviously we don’t watch any of those horrible shows – just singing over the same chords and we’ll do it hours, but going back over the stuff it’s almost always the first idea that becomes the thing.

I think that’s a very psychedelic approach in the sense that it’s instincts happening, it’s pre-thought because you hear the chords and right away you’re recording, so you haven’t had a chance to really map yourself out within that, you just go for it, you’re really throwing arrows out of you and seeing what happens. And I think the psychedelic thing, it forces you to be that open anyway and you can last for hours, obviously, with psychedelics. But even day-to-day, you know, not high, you can still channel that because you’re in a new space, it’s like an adventure but it’s a sonic one, you’re just exploring it with your mouth and the sounds that we make.

HAPPY: I think being open about that also brings a certain kind of audience. Those ideas have been hugely important to rave culture, to electronic music culture…

NICK: Absolutely, and music for me, when it first hit me as a kid was going to raves and it was that hypnotic thing about music, the sticky repetitive things. Or like Vlossom stuff that sounds repetitive, but it’s not – the words keep changing but if you’re a bit out of it, it would feel like the same sentence over and over again, it’s like slightly shifting hieroglyphics right in front of your face and before you know it, you’re in a different pyramid. I really like that kind of patterning, messing with the English language in a way that keeps shifting. You essentially keep painting and twisting.

HAPPY: I love that idea, using hardware to get something that’s so far removed from the physical.

NICK: Yeah. We’ve been in so many writing sessions, and I’m sure most musicians have, where it’s just a dry kind of approach and it’s not really about creating a whole world, but with a few instruments you can really do so much more than a traditional approach, I think there’s so much scope beyond the ordinary or the known or the, you know, the well travelled. Any way we can get there… a lot of it is actually just talking about previous psychonautic adventures rather than having them literally in the studio. It’s more once you start talking about or telling stories about things that you’ve experienced, you get into a different headspace, things just change and come to you in different ways.

But I think that’s what all the gear is about too, like pitch shifting things and Melodyne-ing things, suddenly what you do sounds different when it comes back, you then respond to your own echo because it sounds foreign to you. You can essentially have a conversation with yourself but through a machine, which is making you speak another language or in a different accent. Another colour, or a different time of day.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 14. Order your copy here.