It’s no secret that electric guitarists have spent decades altering the raw sound of their instruments. From the dawn of the rock and roll era, if you could plug it in to something, the guitar was liable to be tweaked in some way. With most archetypal effects though, the true colours of the guitar still shine through. The jangle of the strings can still be discerned through high octane fuzz; the attack of the pick still makes it mark in the most reverberant of tones – in short, the identity of the guitar was never lost. This, however, the was not the goal of the guitar synthesizer.

This machine did away with the inherent tonal qualities of the guitar, replacing them with the sound that was sweeping through the industry, conquering all challengers: the synthesizer. So, how was it born and who were the guitarists that elevated it to an artform? Proceed with caution though: this is a rabbit hole that has led to a lot of credit card damage – and for good reason.

By the late ’70s, the synth was all the rage. But how could guitarists get in on the action? Along came the guitar synthesizer, which has thrived in many forms over the decades.

The Sound of the ’70s

By the late ’70s, guitar effects had not yet plateaued, but it had reached maturity. Hendrix had already set the world on fire with his wah pedal and David Gilmour had sent us to the dark side of the moon and back with epic delays. And that’s just electronic devices. From the bottleneck slides from the early days of the blues, right up until Jimmy Page attacked his axe with a violin bow, guitarists have been looking to extended techniques to create a tonal character that would set them apart.

As well as being a hotly contested era for the development of pedals, the late ’70s was also consumed by a wave of synthesizers. Up until the advent of the Minimoog Model D, these instruments had been in the domain of the avant-garde or the science lab. In simplifying synthesis and importantly, attaching a keyboard, a whole new audience was awakened to the possibilities of the synth. If you were a guitarist though, bad luck.

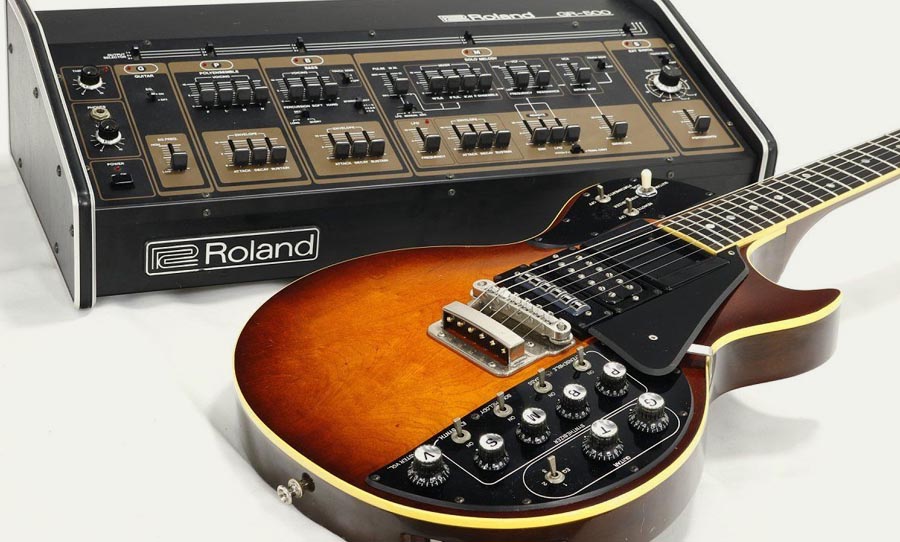

That was until Roland saw a gap in the market launched their own experiment into the field in 1977 with the GR-500 guitar synthesizer. Compared to the kind of sophistication that’s available today, this unit was fairly limited. The polyensemble, bass and solo melody sections are where you’ll find most of the attributes that resemble more traditional synths, with each having an attack, decay, sustain envelope generator in their path and the solo melody section coming with a triangle wave LFO and 24dB per octave filter.

The GR-500 system was not just a piece of outboard though. Roland’s collaboration with FujiGen which meant they had the expertise to develop an actual guitar to accompany the synth. This controller guitar teamed up with the floor unit via a 24 pin interface (remember this is back in ’77, before MIDI was a twinkle in the eye). With the guitar, you could alter the relative volumes of the the polyensemble, bass and solo sections. Each string was isolated with plastic saddles and a hexaphonic pickup system.

Though this synth was groundbreaking in design, in practice it caused many frustrations. Those who’ve gone down the guitar synthesizer road before will know that not all are created equal. Many are plagued by pitch tracking issues and such, make performing guitar parts with typically guitar-based expression very difficult. Despite its performance foibles, its sound was beyond reproach, claiming fame by providing the enigmatic pads in the David Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes.

Things improved with the GR-300 model. It featured one voice per string, with two oscillators per voice. Each of the oscillators could be tuned differently, so some seriously thick and complex pads could be achieved, especially when you take into how easy is to play wide intervals on the guitar. The comparative ease at which it was able to translate expressive playing made it more popular, famously catching the attention of Pat Metheny and Police guitarist, Andy Summers.

Bassists didn’t miss out on the fun either. Roland and FujiGen continued their collab, serving four string players with the rare GR-33B. This model, which also came with its own bass guitar, had similar specs to the GR-300, with four-voice polyphony rather than six. Logically, the bass guitar lends itself to synthesis because it’s typically monophonic and you’re less likely to go for technical gymnastics that are associated with the lead guitar.

Welcome to MIDI

When MIDI did come along, it seemed to be a match made in heaven for the guitarists who wanted to get their synth on. A notable entry into this field, due to its looks as well its implementation of the new-fangled MIDI technology was the SynthAxe, which emerged from the UK in 1985. Its aesthetic was nothing if not striking, with its angled neck and sci-fi body. Though its insanely expensive price (around £10,000!) rendered it commercially unviable, it was favoured by the late jazz fusion legend, Allan Holdsworth.

Much more affordable MIDI guitars from the likes of Casio and Yamaha joined the scene. This was also accompanied by a development in pedals. The Electro Harmonix Micro Synth was a different beast to the offerings from Roland at the time. What the GR-300 had in refinement, the Micro Synth made up for in ease of ease and a healthy dose of attitude. Just plug in your (regular) guitar and away you go. And though the sound is more akin to a fuzz with selectable octaves, the filter section dishes up those sweeps and squelches that send it into synth territory.

The New Era

And while the world is not exactly awash with guitar synth pedals, there is a much better variety for the modern player. There are new versions of legacy devices from the likes of Electro Harmonix and Roland (their BOSS SY-300 takes on the GR-300 mantle, with a similar aesthetic, but with a much deeper feature set – plus, you can use your favourite standard guitar).

The diverse field includes models like the Keeley Synth-1, Earth Quaker Devices Data Corrupter, Digitech Dirty Robot, Death by Audio 8-Bit Pitch and more. While many of the new models are variations on the octave/square wave/filter themes, each strive to create radical interpretations of guitar sounds. While you won’t necessarily be able to pull a perfect impersonation of your favourite polysynth, you can enjoy solid tracking with authentic guitar expression. And you won’t have to remortgage your house.

Bass guitar synth pedals have also enjoyed long-standing popularity. BOSS revived the spirit of the GR-33B and created a compact stompbox call the Bass Synthesizer SYB-5, Electro Harmonix developed the Bass Micro Synth and the newly minted Bass Mono Synth. There have been numerous Envelope Filter style pedals, like the Moogerfooger MF-1 and the Musitronics MuTron III that are just the ticket for dialling in that Bootsy Collins funk.

As you can imagine, this area is ripe for plugin experimentation too. Even some of the classic hardware brands have got on board – the Mini-Synthesizer app by Electro Harmonix for example. Many rely on guitar to MIDI conversion, but the new Roxsyn app relies on proprietary tech to pull authentic synth sounds, all the while accurately tracking idiosyncratic guitar techniques.

Though the sounds might not be for the faint of heart, the evolution of this branch of guitar tone has been fascinating. From awkward beginnings, the guitar synthesizer has been enthusiastically embraced by superstars and weekend warriors alike. And throughout the process, the guitar hasn’t been replaced by the synthesizer – the two instruments have been combined to make a whole new sound that’s more than the sum of its parts.