Arctic Monkeys have made an art out of dignified risk-taking in their career, and 2013’s AM was an exercise in experimentation, masterfully executed.

Most musical acts are hard to put to maintain both relevance and quality throughout their entire career; Arctic Monkeys, though, have made simultaneous mainstream success and critical acclaim look effortless. In fact, despite one of the most explosive debut albums in the history of pop music, they peaked internationally with their fifth album: the tour-de-force that was 2013’s AM.

A commercial and critical hit, AM was buoyed by the lead single Do I Wanna Know?, which aided a Monkeys’ breakthrough in the US. New heights were also reached in the UK where they became the first band on an independent label to debut consecutively at #1 with all five of their albums.

For AM, the band once again employed long-time producer James Ford, in addition to electronic heavyweight Ross Orton, to create an album that fuses hard rock and R&B in a way that screams musical growth done right. Thunderous Sabbath-inspired riffs appear right alongside bass lines drawn from West Coast hip-hop.

“With AM, it was just simply an experiment,” frontman Alex Turner summarised to NME, “But at least if you’re doing an experiment I think you’re moving in a healthier direction.” As far as experiments go, AM was a raving success, named the best album of 2013 by NME and widely regarded as the best of the band’s career.

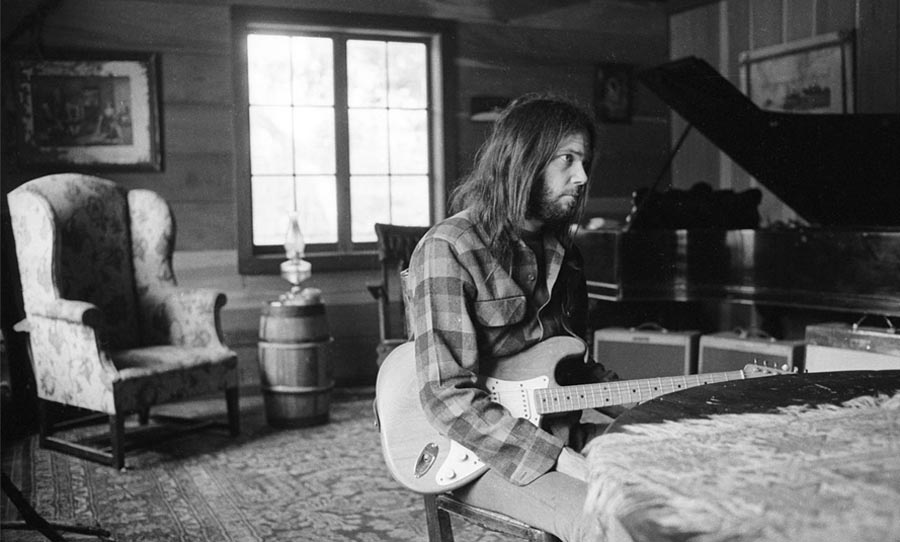

Both rehearsed and recorded at LA’s Sage & Sound, AM was the outcome of roughly half a year’s daily jamming. Ford admitted to NME that he was initially sceptical of the choice of locale: “When they first came to me they were like, ‘We’re thinking of recording it in our rehearsal room’, and I thought, ‘Er…alright’.” But the Hollywood studio, fashioned with wood and faux Greek architecture, won Ford over with its antiquated charm.

To suit the aesthetic, demos for AM were hatched with a ‘70s 4-track cassette tape. Gifted to Turner for his birthday, the tape became the primary source for much of the record’s final material.

According to drummer Matt Helders, its “crap-quality electronics” allowed for unique warmth of sound not found in digital alternatives. Taking the process into the 21st century, Ford later cultivated these demo loops on good old Ableton Live.

Months and months of recording were then followed by tracking sessions at Rancho de La Luna in Joshua Tree, California (where the band had experienced a spiritual and musical awakening during the recording of 2009’s Humbug), a process that was arguably more integral to the album’s sound than even the writing itself.

So, how exactly did AM stun the critics and masses alike? In appreciation, we examine a few of the production innovations that lent the album its particular magnetism.

Instrumental Miscellany

Inclusion of atypical instrumentation was part and parcel of the Monkeys’ experimentation, ranging from classic drum machines to a guitaret to a synths. Perhaps most interesting of all was a Donald Duck plastic fan in place of an Ebow.

“Dre” Grooves

Verging from the garage virility of the band’s earlier days, AM was above all concerned with rhythm. Bass and drums were recorded first, with all other parts built around this rhythmic crux. The upshot was an out-of-character hip-hop influence that caused the band not a little anxiety. “With this new one, we were asking, have we gone too far?” Turner confided in Uncut. “Does it sound too much like Dr Dre or something? Then you play it to someone and they wouldn’t even pick up on that. But they can tell it’s us.”

Beats Like (or From) a Machine

From equipment to technique, the drum and percussion tracks on AM exemplify the Monkeys’ era of innovation. They turned to Vox Studios for their first ever dabble with drum machines, namely vintage Thomas Bandmaster and Selmer models. It’s the Selmer that can be heard on slow jam I Wanna Be Yours making use of the machine’s ‘Liverpool’ setting and in combination with a Fairchild spring reverb.

Electronic-sounding percussion is achieved elsewhere with unconventional techniques and plentiful layering. A striking instance is Fireside, for which Helders first recorded a standard beat, and later layered over it an incessant kick loop recorded separately. For this particularly tribal beat, Helders’ method was banging it out on the kick drum with a pair of sticks.

“I found the challenge of playing an effect on a drum kit interesting,” Helders told Emusician. “I didn’t understand the appeal of trying to sound like a machine… when I first started playing drums, but I get it a bit more now.”

Layering of separate tracks was common practice during production, with the kick to snare to tom sounds often recorded separately with a SansAmp Classic preamp. Afterwards mixing engineer Tchad Blake had it all parallel-compressed for double the punch.

Vocal Multiplication

Another striking element of AM is the band’s soul-redolent layering of lead and backing vocals. It became routine for Turner to re-record his lead vocals up an octave for the sake of doubling. Helders then backed up Turner’s falsetto with his own, also up the octave, while O’Malley provided yet another layer with an octave down from the original key. The “ooh la la la” outro of Mad Sounds is arguably the primmest example of this vocal feast.

Nonetheless, the equipment was all fairly conventional stuff: a Universal Audio 1176, Empirical Labs Distressor, and a BAE clone of the Neve 1073. A Neumann U67 microphone was the main player here too.

Things got truly interesting in post-production, where all of the record’s vocal flair was realised through a truly compulsive level of editing. Turner has admitted that it went to the extent of chopping up his vocals syllable by syllable on Pro Tools in order to piece together the perfect take.

Strings, Keys and The Relationship Thereof

Most stuff plugged in was familiar: a vintage Selmer Truvoice and Magnatone Custom 410 for Turner and Cooks’ guitars, mainly, and a vintage Ampeg Portaflex for O’Malley’s P-bass. There was also Turners’ 12-string Vox guitar, on which he wrote the iconic riff from Do I Wanna Know?

However, memorable addition to the studio was Turner’s new Rickenbacker pedal steel amplifier, heard on No. 1 Party Anthem. Small and compact, it was christened “The New Black” – also known as the original album title.

Something else new was the Monkeys’ interest in keys, which they indulged to the fullest at Vox Studios. There they seized on not only a piano but also a celesta and Vako Orchestron organ synthesiser.

Not inclined to stop there, the group also went to the trouble of making some of their guitar sounds mimic keys. Doubled guitar lines are rampant on AM, often with the use of a Hohner guitaret of all things.

In the spirit of the album’s elaborate tracking sessions, Turner and Cooks’ guitars were recorded individually, and bass lines in Knee Socks also were doubled with a baritone guitar. The aforementioned Donald Duck fan came in handy as a guitar-playing tool – once turned on, its vibration against the strings produced a wholly unique keyboard effect.

Poetic lyricism

Technical tricks aside, one of the immediate charms of AM is the simultaneously effusive and tongue-in-cheek way it goes about expressing universal experiences. Take album closer I Wanna Be Yours, a musical reworking the work by punk poet John Cooper Clarke. Opening with the line “I wanna be your vacuum cleaner/breathe in your dust” it’s a beautifully comical love song delivered completely straight.

“The humour you get in his poetry is something I thought you could have in songs,” Turner expressed in The Australian. “At that stage, you’re really worried about being taken seriously, in the beginning. The moment you stop putting humour in there is when you’re worried you’ll cross the line and it won’t be taken seriously. John kind of walks that line.”

Arctic Monkeys walk that line, too, considering the popularity of singles Why’d You Only Call Me When You’re High? and Do I Wanna Know? Balance is key, and as AM shows, the band have made an art out of dignified risk-taking.