From beaten-up 8-tracks to beefy kick drums and erratic guitar tones, we take a peek at the making of The White Stripes’ fourth album, Elephant.

by Oliver Newland and Anthony Sfirse

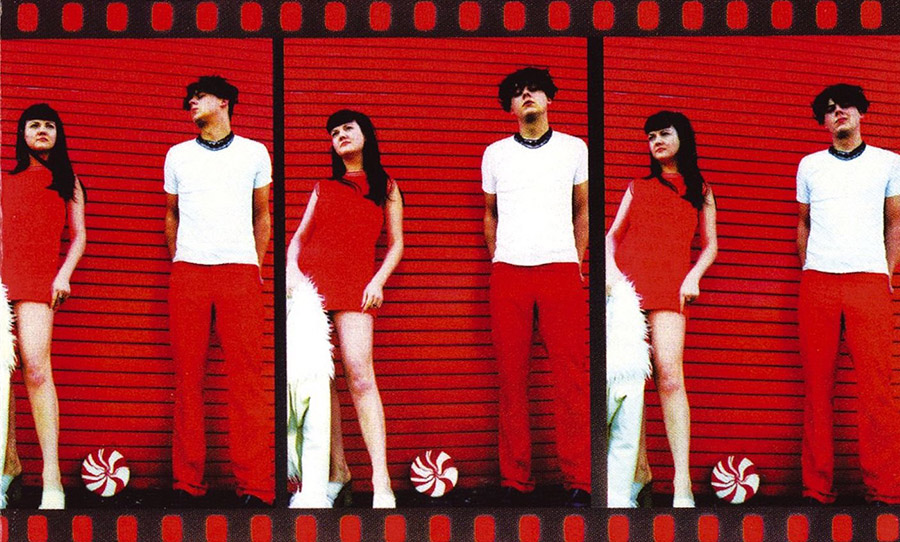

Still to this day, few bands are able to match the unbridled energy and tenacity of a White Stripes LP. Formed in the heart of Detroit back in 1997, the duo of drummer Meg White and guitarist/vocalist Jack White had found minor success in the then-emerging garage-rock revival before the turn of the millennium, thanks in part to their erratic live performances and their rough, blues-heavy sound.

The band’s third album, 2001’s White Blood Cells, saw The White Stripes achieve critical acclaim from various media outlets, with their touring schedule beginning to drastically sprawl across the globe. Expanding on the album’s stripped-back approach to writing and recording, The White Stripes began to lay the groundwork for what would be their most commercially successful album – 2003’s instant rock classic, Elephant.

The Allure of the Analog

By the turn of the century, many garage-rock artists started to reject the sheen and slick audio production that had become the standard of mainstream rock at the time. The Strokes and The Hives both were praised for their “back to basics” approach to recording and songwriting. Not ones to be content with resting on their laurels, The White Stripes aimed to expand on what they had achieved with White Blood Cells and their DIY outlook on recording, taking their blues-rock tone on a trip through time.

After extensive touring, Meg and Jack White recorded Elephant inside the confines of engineer Liam Watson’s cramped recording facility, London’s Toe Rag Studios. In defiance of digital recording techniques that had become the standard in studios, Toe Rag didn’t contain any recording equipment manufactured after 1963. In the album’s liner notes it famously states “No computers were used during the writing, recording, mixing, or mastering of this record.”

Utilising a beaten-up eight-track tape recorder, an 18-input Calrec M-Series mixer and the plethora of weary microphones laying around Toe Rag – including an old STC 4021 microphone more commonly known as a ‘ball and biscuit’ – The White Stripes were able to create fourteen songs over the space of ten days that dripped vintage allure.

Not only did the antiquated equipment provide the songs with some ham-fisted gritty warmth, it also helped the duo’s streamlined, on-the-fly recording process. Speaking with Sound On Sound in October 2003, Watson spoke on how high-end, modern recording gear can at times negatively affect the process: “You don’t need to f**k around with stuff because if it sounds good in the room, if you’re using the right microphones in the right positions it should sound good in the control room as well. The less you do, usually the better it sounds.”

Crafting Their Sprawling Sound

Cooped up in the retro-tinged confines of Toe Rag Studios, Jack White acted as the producer for Elephant, wanting to specifically explore just how big of a sound two artists could create, while being limited to just eight individual tracks per song. This challenge saw the duo incorporate an instrument not yet heard on a White Stripes song: a bass guitar (or so it seemed).

Few rock songs in the 21st century have had the impact and legacy of Seven Nation Army; a sleek and sinister descending riff that has since been etched into the minds of literally everyone across the globe. Released as the album’s lead single, the song’s iconic bass riff was actually recorded without a single bass guitar.

Instead, Jack White used a semi-acoustic 1950’s Kay Hollowbody guitar and ran it through a Digitech Whammy, one of the few post-1960’s pieces of gear used on the album. With the pitch on the Whammy pedal set an octave down, White’s menacing riff was suddenly given a ton of weight and depth – an effect also used on the opening beats of The Hardest Button to Button.

While other tracks on the album like In The Cold, Cold Night and I Want To Be The Boy To Warm Your Mother’s Heart use organs and piano for a fuller and richer tone, no recording technique was more effective in adding scope to Elephant than multi-tracking.

This is perhaps best put to use on There’s No Room For You Here, a song that sounds somewhat out of place on the album due to its grandiose arrangement. Boasting breathy vocals stacked on top of each other, rhythm and lead guitar tracks and a heaving organ deep in the mix, The White Stripes were able to mimic the grand scale of a Queen song – no easy feat for a band limited to a worn-out eight-track tape recorder.

Chest-Thumping Beats

A key component of The White Stripes’ garage-rock sound has been the drumming style of Meg White, who usually takes a more reserved, simplistic approach to the drums than most of her contemporaries. Nonetheless, her laidback drums fused perfectly with the frenetic energy of Jack White’s guitar, and on Elephant, her beats were given a much-needed boost.

One of the hallmark qualities of Elephant are the head-bursting thuds of Meg White kick drum. This was achieved by miking Meg’s Ludwig Classic Maple kit with both AKG dynamic and condenser microphones, as well as a Shure dynamic mic for the snare. On many songs, the drums are mixed onto one track – except for the bass drum. The bass drum, for many songs, has its own track, which was compressed and brought to the forefront of the mix, particularly on album cuts like the opening number and The Hardest Button To Button.

Jack White: The Virtuoso

At the core of The White Stripes’ sound is the blues-heavy and often-erratic guitar tones of Jack White. Looking to thicken the sound of the band, Elephant saw White experiment with guitar overdubs, allowing the songs to feature both a rhythm part and a wailing solo simultaneously.

Jack White’s setup was kept relatively straightforward. Other than the previously mentioned Kay Hollowbody guitar, White’s main axe for the album was a 1964 ‘JB Hutto’ Res-O-Glass Airline guitar. This was often plugged into a Fender Twin Reverb amp or a Silvertone combo miked with Shure and AKG dynamic mics, with each amp having usually having its own track.

Though Jack White achieved a myriad of different guitar tones throughout the album’s 50-minute run-time, he does so with just two guitar pedals. White’s tone was heavily reliant on the famous Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi, which he uses for most songs; from the touch of gain on Ball and Biscuit through to the rough, crunchy swagger of Black Math.

The other guitar pedal that’s vital to Elephant’s guitar tone is the Digitech Whammy WH-4. While it’s most well-known for creating the rumbling faux bass parts scattered throughout the LP, the pedal was also used to take the guitar to new, ear-piercing heights, best heard on Black Math and the guitar solo on There’s No Room For You Here.

Jack White has often professed his love for the pedal: “The Whammy enabled me to get an octave higher than everybody else, so I could break through for a few seconds and do a lick and then come back to the song. And now I just want solos to be an octave higher and piercing…”

From subtle finger-picked octaves to distorted slide solos, Elephant’s warm tone and creative limitations allowed Jack White to fully flesh out his virtuosic guitar capabilities. While the album is best known for its analogue soul and Seven Nation Army’s slinky riff, Elephant will forever be remembered as the album that cemented Jack White as one of the most visionary guitarists of the 21st century.

Read more White Stripes articles here.