As the 1980s loomed, change was afoot in music technology. The electric guitar revolution that was launched a couple of decades before had reached its zenith; rock music was at saturation point in popular culture.

Synthesizers emerged on the world stage in the ’70s with the Minimoog leading a charge of newly accessible electronic instruments. The new sounds birthed new kinds of music, but the synths that used analog oscillators for sound generation had a specific identity and limited scope.

At the forefront of this new wave was an invention from Sydney, the Fairlight CMI (Computer Musical Instrument). The teenage duo of Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel combined their musical passions and computer expertise in a machine that would have an outsized impact on music creation, especially in the 1980s.

The Fairlight CMI star shone brightly, but it was too far ahead of its time to survive. Read on to explore its place in the history of electronic music.

Digital power

Analog synths were able to traverse new, otherworldly sonic landscapes, but it wasn’t until the advent of digital technology that musicians could have their cake and eat it too: access to original sounds, plus the ability to produce unprecedented realism through sampling.

Towards the end of the 1970s, microprocessor technology gained a foothold in a variety of industries. As evidenced by the devices that power our lives today, the significance of this digital development is impossible to overstate.

As the ’70s clocked over to the ’80s, music and audio technology was at a crossroads. Pivotal digital machines infiltrated the studio. Delays and reverbs took on a new identity through the AMS DMX 16, the hard-hitting grooves of Linn LM-1 rippled throughout the decade and the Fairlight CMI was revolutionising electronic music through sampling. Later still, a trinity of digital synths – the Yamaha DX7, Roland D-50 and KORG M1 – spelled the death of commercially viable analog synthesis.

Big dreams

Like so many, Kim Ryrie was turned onto the sounds of electronica through Switched-On Bach, recorded by Wendy Carlos (who was Walter Carlos at that time) in 1968. This baroque expedition married the decidedly old with the sounds of the future: the Moog analog synthesizer.

In childhood, Peter Vogel had a habit of overshooting the mark. On a school assignment about the post office, the pre-adolescent Vogel eschewed the typical book reports in favour of building and demonstrating a home-made fax machine – around 15 years before they were invented.

Ryrie and Vogel became school buddies and stayed in touch throughout various young adult endeavours. While the two witnessed the dawn of the microprocessor in the mid-1970s, Ryrie suggested to Vogel, “How about we build the world’s greatest synthesizer?“*

A digitised version of the analog synthesizer was to follow. An instrument that could bridge the worlds of fantasy and reality in a way that was yet to be conceived.

The big debut

When the Fairlight CMI finally hit the market in 1979, it utilised the best microprocessing technology money could buy. The sampler had the capacity to store 28 megabytes of memory, with the processor itself sitting in a 24-inch module. Topped with a monitor and QWERTY keyboard, this was every computer nerd’s fantasy come to life.

It’s one thing to create a groundbreaking instrument, but another to get it into the hands of musicians. This could’ve been an uphill battle for this independent partnership from Sydney. Another thing that made it an uphill task its the astronomical price of approximately $25,000.

Through a serendipitous connection (a neighbour of Vogel and Ryrie’s workshop was Bruce Jackson, founder of JANDS and live sound engineer for Elvis Presley), Fairlight had their entrée into the United States market. On the strength of a single prototype, Vogel went on an all-star studio tour. The first Fairlight customer: Stevie Wonder.

Version II appeared in 1983. Again, with an eye toward incorporating the latest tech, it shipped with newly available MIDI capability. The CMI III was the last to emerge in 1985, packing 16 voices of polyphonic power. Being admitted non-musicians, the sequencing capabilities that Ryrie and Vogel designed for all three versions were sophisticated – providing ample opportunities for people who weren’t keyboard virtuosos to get a lot out of these instruments.

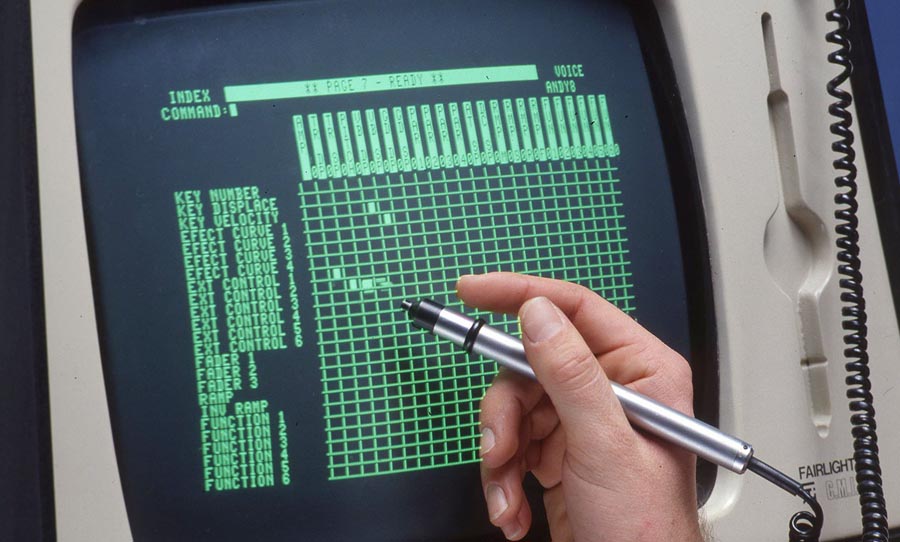

The visual interface of the CMI was also key to its success. There was quite simply nothing else like it at the time and considering the ubiquity of the DAW in modern production, the CMI’s graphical workflow was a harbinger of things to come.

The screen and light-pen was the composer’s gateway into the world of sequencing and editing samples. Nowadays, a generation of studio enthusiasts has known nothing but the interface between sounds and screen: editing audio, juggling clips, drawing MIDI notes via the piano roll – all these archetypal functions of the modern workflow found their genesis in the tiny monochrome monitor of the CMI.

But it was sampling that was at the core of the Fairlight story. The ability to record a real instrument – or any sound for that matter – and spread it across the keys of the workstation was nothing short of revolutionary. And as more musicians got the CMI in their hands, this sample library grew, along with the Fairlight legend.

A new approach

Musicians saw huge potential in the way samples could be used creatively. With the CMI as part of their toolkit, artists could take a whole new approach to production but still maintain total musical control. It also served a practical purpose: sound designers and film composers could replace entire orchestras with the CMI and shape the tone of traditional instruments in new and exciting ways.

Peter Gabriel, a prog-rock icon and notorious audiophile did more than most to stretch the capabilities of the sampling engine. In his collaboration with Kate Bush, he used the CMI to capture the sound of smashing glass on Babooshka.

For film composers, entire universes of editable orchestral sounds were opened up. For example, the score for the action epic Terminator 2 was composed using two Fairlight CMI IIIs. Yes, there were samples of real orchestral instruments on hand. Integral to the atmosphere of the movie, however, was the unnatural morphing, repitching and layering of sounds.

Played back at normal pitch and speed, the samples sound prosaic, even silly in isolation. Shoehorned into completely unrealistic pitch areas and speeds, twee violins and trumpets take on the foreboding tone of the Terminator. The CMI made it possible to rethink the very fabric of sound.

Ahead of its time

Owing to the eyewatering expense of the Fairlight machines, the broad uptake of personal computers, and adoption of digital synthesizers that had faster and more intuitive user interfaces, it was bound to be a short life for the CMI. The company went broke and Vogel and Ryrie went their separate ways. Being ahead of one’s time can be dangerous: the infrastructure and technology to support a company like Fairlight simply didn’t exist.

Sadly, Peter Vogel – who licensed the Fairlight trademark in order to market and manufacture a commemorative edition of the CMI in 2009 – has been embroiled in a protracted legal dispute with Fairlight’s trademark owners, who picked up the trademark after the company folded (which could’ve explained Vogel’s reluctance to participate in an interview). Remarkably, he earned a law degree during the time the case has been before the courts. And still, it drags on.

No doubt it’s been a wild ride for these school mates. At every stage, they extended beyond what they thought was possible and in a way, they were comically unprepared for the tidal wave of success (a host of celebrity clients had pledged thousands of dollars before the instruments were even made). Only now, since the world has finally caught up to Vogel and Ryrie’s vision, can we understand the CMI and its place in our imagination.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 14. Get your copy here.

* Cited in a NAMM Oral Histories interview, September 8, 2017.