In the late 1970s, right here in Sydney, there was an auditory revolution that was being developed by two men, Peter Vogel and Kim Ryrie, that would eventually help to encompass the sound of the 1980s. That instrument was the Fairlight CMI.

The machine’s ‘CMI’ name eventually came to symbolise how synonymous synthesizers (such as those made by Roland) would be for the coming decade, and what those ‘computer musical instruments’ as a genre of instruments did for the 1980s and what the decade sounded like as a whole.

A pioneer in computer music, the Fairlight CMI revolutionised production throughout the 1980s and spawned entirely new genres of music.

Of course, having the name ‘Computer Musical Instrument’ does give some idea of what it is all about. The first version of the instrument was released in 1979 and with the final series three model of the CMI being produced by the mid 80s.

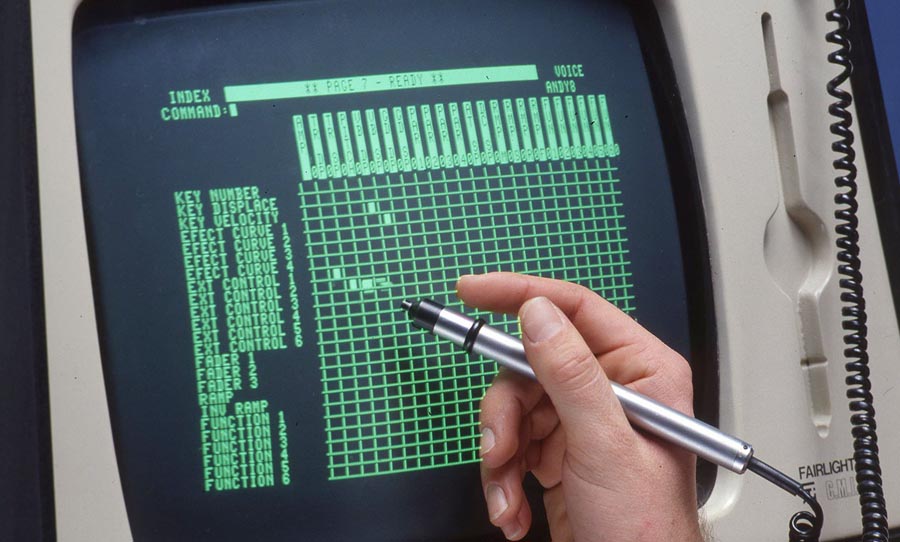

Being designed in the late 1970s, it does have the tropes that people tend to think of when they think of early computers, like the green on black graphics, the noisy floppy disk drives that help run the instrument, along with a quintessentially 80s QWERTY keyboard.

All of these work in conjunction with a 73 key piano keyboard, all operating through the instruments’ 208kb of onboard RAM, which by today’s standards is positively Stone Age, but state of the art for the time. However, having gone through several revisions in the early part of the 80s, the most well-known version of the Fairlight CMI is the IIx model which was released in 1983, starting at the astronomical price of $50,000.

While the IIx continued the evolution of the CMI, with the on board light pen being used to draw harmonic curves in real time, the IIx version of the Fairlight also included for the first time a MIDI controller and the legendary ‘Page R’ sequencer, as well as a higher sampling rate of 32KHz versus the CMI I and II’s 24KHz.

This was loaded onto the system in a series of 500kb floppy disks (the really old 5 ¼ inch ones, which actually were floppy!), with 22 sounds per disk, and with this you could access the ‘Page R’ sequencer, where each note was represented graphically on the screen (where individual notes could be manipulated with the built-in light pen), and each piano key ‘contained’ a single instrument or a musical sample that was loaded into the system (typically only a few seconds worth of sound, thanks to the technological limitations).

Because of the Fairlight’s ability to store samples with eight voices and up to 50,000 musical notes at a time, many high profile musicians and music producers became enamoured with the machine and its capabilities, with some wealthy musicians buying a CMI after only seeing what the Page R could do relative to its nearest competitor, New England Digital’s Synclavier.

Despite the fact that by the standards of 2017, the Fairlight’s technical specifications are hilariously archaic, it’s pretty clear that the CMI, along with the use of MIDI technology, the light pen system and the Page R sequencer were instrumental in helping to provide the sound of the eighties, where the instruments ubiquity reached the point where Phil Collins’ No Jacket Required even had to state that “There is no Fairlight on this record.”

Other artists who used the Fairlight CMI extensively were Peter Gabriel with his solo records (where he sampled the sound of glass breaking for his recordings using the Fairlight), French ambient musician Jean Michel-Jarre , and bands such as Frankie Goes to Hollywood (where the Fairlight appears on the track ‘Relax’) and the musical collages of the Art of Noise (whose signature track- the lush, down tempo ‘Moments in Love”, was 10 minute futuristic lullaby created entirely on the Fairlight), both of which were produced by Trevor Horn.

As significant as the CMI was, by the mid-80s interest in the Fairlight started to wane, as the high price and lack of portability began to be challenged thanks to cheaper packages such as the MIDI-enabled Atari ST computer, and digital sequencers by companies such as Akai. While Fairlight is still around today, it has nothing to do with the original company that produced the CMI all those years ago.

As for the impact that the CMI has had on electronic music, the Page R sequencer is probably its most significant contribution to the genre, as it paved the way for the development of Digital Audio Workstations like Ableton Live or Logic ProTools with its relatively simple layout, enabling sampling to be user friendly, making the idea of sampling and music-making attractive to non-musicians by representing the music in a graphical fashion.

As for the recordings created with the help of the Fairlight CMI, those recordings have gone on to be crucial to genres such as drum and bass, techno and a whole host of other electronic music genres. So, while the Fairlight might be crude by today’s standards, remember that without it, the world would sound very different.