Minimalism transports the listener to a place of contemplation – where new sounds can be imagined in the midst of silence. We explore its power in modern production.

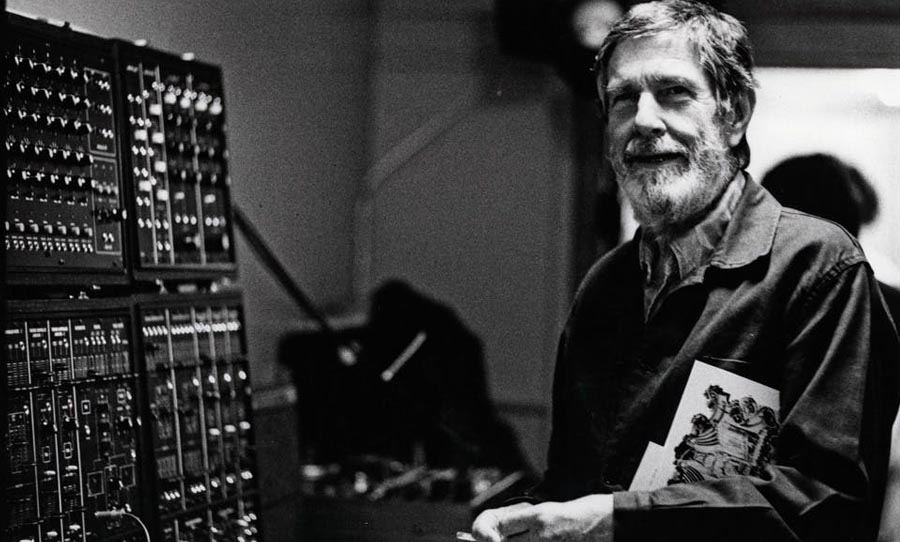

In 4’33”, John Cage laid down an interesting challenge for musicians and audiences alike. The score instructs the player to k play his or her instrument for the entire duration of the three movements of the piece, totalling four minutes and thirty-three seconds. To many, this is the very definition of minimalism.

Is it though? The minimalism that refers to the particular school of American avant-garde composers that emerged in the mid-20th century can actually be quite noisy. Take Clapping Music by Steve Reich for example. There’s minimal rhythmic variation and it’s devoid of harmony, melody, or any kind of pitch information. Yet, it’s full of sound.

Both these forms of minimalism have been applied to modern production techniques. The mantle of fundamental sparseness laid down by John Cage has been picked up by artists like James Blake and transformed into something new. The conceptually minimalist traditions established by Reich have been absorbed and sublimated by bands like The War On Drugs.

Modern artists have imbibed the mantras of minimalism and have created new ways for this musical philosophy to live on in new and original ways. Let’s discover how.

The catalogue of the minimalists and avant-garde composers of the 20th century stood well apart from the burgeoning style of pop. Cage first imagined 4’33” in the late 1940s, an auspicious time in musical history: the pre-dawn of the electric guitar revolution. In the early 1950s, Leo Fender and Les Paul electrified music and the world’s ears were tuned to the sound of rock ‘n’ roll.

The avant-garde soldiered on but was mainly the preserve of academia. With teenagers the world over screaming for the sounds of the rock ‘n’ rollers and later, the British Invasion, there was scarcely any room for the contemplations of Cage, with his music influenced by the tenets of Zen Buddhism.

As popular music reached maturity and diversified, Brian Eno bridged the gap between the anachronism of the avant-garde and the broad melange of popular music. Early in his career, he made his name by bringing the synthesizer into the realm of rock as part of Roxy Music, a ’70s powerhouse that was fronted by Bryan Ferry.

He was also collaborating with King Crimson guitarist, Robert Fripp and together they were pioneers in ambient tape-looping, a technique dubbed ‘Frippertronics’. It wasn’t until the seminal Ambient 1 – Music for Airports that a new marker was laid down for the field of ambience. It’s a journey with minimal variations in concepts of harmony and melody, with phrases that are only connected only by reverberant space. It was a perfect combination of both interpretations of minimalism and what’s more, it brought this meditative style to the consciousness of modern pop artists

Sure, it would take a brave artist to go down the road of Steve Reich and compose a piece of music using only the body. The structure of pop music is rigid – verses and choruses are everpresent – even if the order is altered, the A section to B section dichotomy seems inescapable. Minimalist and ambient tendencies tend to shine through in production techniques.

Take Drake for example. A successful hip hop artist at his level would have the means to incorporate as many layers as he wanted into a lavishly maximal production. In his recent release, War, his sound is instead typified by the absence of layers. The focus is drawn to his voice – with its rhythmic intricacy and only minor variations in pitch is itself a study in minimalism. The background layers feature repetitive harmonic information, anchorless without a recognisable bass voice until well into the song.

This interpretation of minimalism – delicately crafted slow-moving harmonic layers, which draws the listeners attention to the intimacy of the voice can be found in the work James Blake, Radiohead, Beach House and more. But there are some modern artists that have followed the examples of the Steve Reich/Philip Glass school of minimalism i.e., maximum sound with minimal musical concepts.

One of the more striking examples is Spiders (Kidsmoke) by alt-country icons, Wilco. The band’s usual M.O. – richly layered harmonies, lyrical melodic arcs and unpredictable forms – is anything but minimal. But on Spiders (Kidsmoke), they’ve taken a leaf straight out of the textbook.

For most of its more than ten minutes in duration, guitars and bass hammer away incessantly on a single note, lulling the listener into a trance, only broken periodically by Jeff Tweedy’s spaced-out vocal phrases and tortured, atonal electric guitar. The tension is only released a full four minutes into the odyssey, when the band explodes into a wordless ‘chorus’, only to return to the relentless monotone groove.

The same technique is exemplified in minimal house and techno, styles that are perfectly suited to the precision of electronic music. The same undulations found in Spiders (Kidsmoke) can be found in the club, only stretched to even further extremes of time. The rhythmic increments underpinned by a higher tempo four-on-the-floor kick drum may inject momentary energy into a room, but the long-term interest is sustained by the glacial pace of harmonic and bass layers.

Viewing modern music through a minimalist lens forces us to look twice at our definition of silence. As with Cage, Eno and even Drake, it can be appreciated for its literal lack of sound. But with Glass, Reich and later, Wilco, minimalism can be interpreted in another way – a shedding of extraneous musical ideas and clarity of concept, which is in its own way, just another version of silence.