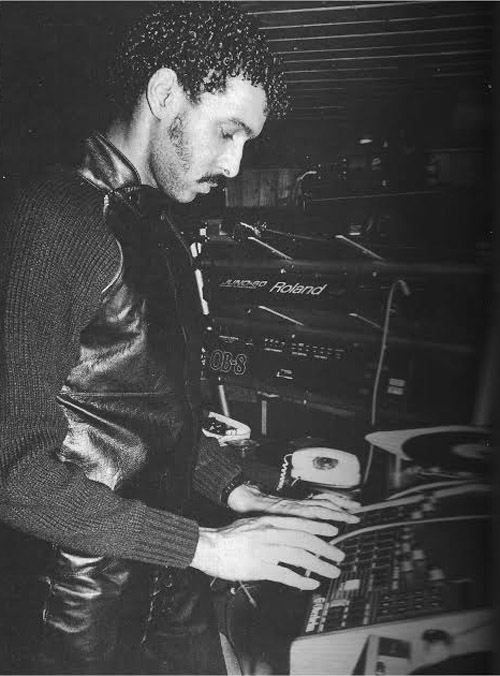

In many ways, the sonic style of the ’80s was characterised by the embrace of new technology, without necessarily complying with the notion of realism. Digital technology approached maturity, studios were gifted with unprecedented multitracking power and instruments like the Oberheim DMX drum machine sliced through mixes with a sound all of its own.

Along with the seismic impact of new technology came a proliferation of genres that were previously inconceivable. And from the New York underground came hip hop, a style with rhythm and swagger at its core and therefore made for hard-hitting grooves of the Oberheim DMX.

The Oberheim DMX rose to prominence alongside hip hop. It quickly became an indispensable tool for crafting beats and creating the infectious grooves that typified the genre.

Hot Competition

In synthesizer and drum machine development, the early 1980s was the most fertile period in history. Previously unattainable synthesizers were rapidly becoming cheaper and more user-friendly. Drum machines shrugged off their previously gimmicky identity and became legitimate vehicles for artistic expression, with deeper capabilities than ever before.

On one side of the Pacific, Roland was breaking new ground with the TR-808 – a drum machine with an analog sound engine – basically a synth that was capable of crafting “drum-like” sounds. Those who’ve heard an 808 though will tell you that “drum-like” can only be applied loosely here. Yes, there’s no doubt that it is an awesome instrument, but real drum sounds it could not pull off.

Real drum sounds are best created from real drums. This is where sampling came into play. Roger Linn’s experiments with this method resulted in the release of the LM-1 in 1980, an inspirational forerunner to Tom Oberheim’s DMX.

At this point, digital sampling was a strikingly fresh technology. Previous successes with this method of sound production included the Aussie-made behemoth, the Fairlight CMI. Notwithstanding the technical miracle, the major drawback of digital sampling in this era was that it was expensive and obviously hard to implement on a commercial scale.

Upon its release in 1979, the Fairlight CMI cost an eye-watering $30,000, the Linn LM-1, though cheaper was still quite pricey at around $5,000, still enough to make it a difficult commercial proposition. The DMX was slightly more accessible at around $3,000 on release in 1981. While the LM-1 had 12 sound to choose from, but the DMX had 8 channels which offered 3 sounds each, meaning the whole pallet was double that of the LM-1.

Getting Creative

The DMX presents the user with an exceptionally friendly interface for creating sounds. Arrayed on the front panel are 8 faders, 1 for each channel, with 3 variations on each. There’s a channel each for bass, snare, hi-hats and cymbals, with toms and percussion (tambourines, shakers, rimshot and clap) spread across 2 channels each.

On the rear panel are outputs for each channel, plus a mixed output section, clock input and output for syncing with other sequencers, synths or drum machines. It also has a keypad section that could be used to change sequences and songs, as well as record and add a shuffle feel to the beats.

Up until the release of the DMX, hip hop producers would mainly rely on sampled beats and loops from records to stitch together their beats. While this method had very much a character of its own and is still favoured by many, the methods for manipulating these samples were crude and didn’t allow much creative scope.

With the DMX, producers had free rein to create full songs, with a broader range of expression available to them. Hip hop caught the MTV wave in the ’80s and the tight, crisp and comparatively hi-fi sounds of the drums emanating from the DMX provided the backdrop to this phenomenon.

Davy DMX (the name is not a coincidence) was particularly smitten with the new invention, using it to infuse his gritty New York productions with a slickness and punch that helped hip hop break into the mainstream. He used it on his own work and with fellow New Yorkers Run DMC and Kurtis Blow.

But as you can imagine, the influence of the DMX didn’t just stop at hip hop. It made its way onto pop hits like Into the Groove by Madonna, Sussudio by Phil Collins and Stand Back by Stevie Nicks. It ventured into electro-jazz, immortalised in the beat of the Herbie Hancock‘s Rockit and was often paired up with acid bass machines in dancehall music. It also propelled the new wave genre, playing a starring role on New Order‘s Blue Monday.

The overwhelming character of the DMX played a unifying role amidst the myriad genres that it featured on. It’s sequencing capabilities, combined with intuitive playability, meant that it was easy to infuse tracks with its relentless snare fills, intensely robotic hi-hats and that clap.

In the same way that Linn LM-1 spawned the LinnDrum, the DMX was succeeded by the DX. In some ways, it was the little brother, with fewer sound sources, but it also enjoyed improvements like easily accessible individual tuning knobs for each channel.

Whichever flavour, both the DMX and DX maintained the same essential soul. A groundbreaking instrument that did more than its fair share to shape the unashamedly electronic sounds of an entire decade. Even if you don’t know it by name, the sound of the Oberheim DMX has already left an indelible imprint on your memory.