When Eventide took its first nervous steps into the competitive world of pro audio, digital effects weren’t a thing. Yes, engineers and studios had set forth in their quest of artificial ambience, but it was very much in the mechanical realm.

If you wanted reverb – it was more fashionable to call it ‘echo’ way back then – you rely on spring tanks, which Fender amps made famous. You could wheel around massive plates – like the ones made by EMT -if you were lucky enough to have the space. Better yet, there was the echo chamber: pipe sound into a reverberant chamber, record it and bring it back into the mix (see Capitol Studios).

To achieve delay, there was tape method, popularised by Les Paul, plus a couple of mechanical options like the Binson Echorec, made iconic by David Gilmour.

Eventide were true pioneers in the effects field. They experimented with the microchip, shrinking the footprint of effects units and making them attainable for studios all over the world.

Eventide harnessed the power of digital technology to bring reverb, delay and modulation to studios across the globe. Along the way, they’ve created plenty of iconic sounds.

Digital dark age

Like many successful business partnerships, Eventide started as a meeting of practical and inventive minds. Stephen Katz was a recording engineer in New York City and he had a problem: no room for a ‘tape-op’. Being a tape operator used to be a rite of passage in the studio, back when tape machines ruled supreme. Katz’s studio didn’t have the space for a tape-op, so he needed a solution for finding tape locations in the heat of a recording session.

Katz tapped Richard Factor to build a unit that would serve this purpose. Orville Green, the owner of the studio, stumped-up the cash to build the unit. They were soon joined by Tony Agnello, a recent graduate in the study of signal processing. Eventide was born.

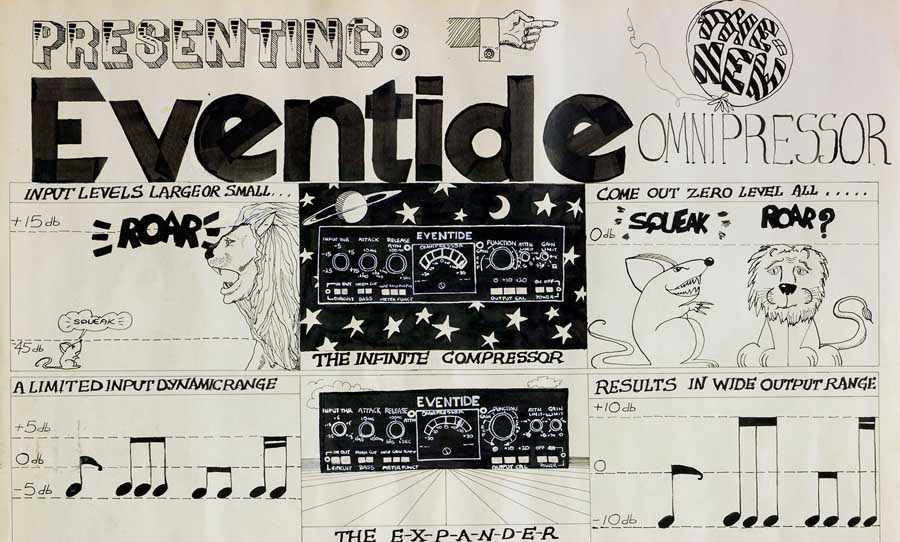

Despite being famous exponents of digital tech, Eventide’s first noteworthy products used analog circuits. The Omnipressor dynamics processor (which is still so popular it survives in plugin form), which encompassed compression, expansion and gating and the 101 Instant Phaser, which uses filter circuits to replicate the sound of tape-based modulation.

Delay breakthrough

The practicality of delay (or lack thereof) forced the Eventide team to consider digital technology. There were already elegant solutions for reverb. Outboard compression was already well established, with offerings from Fairchild and Universal Audio used commonly in professional studios. Delay was a different proposition.

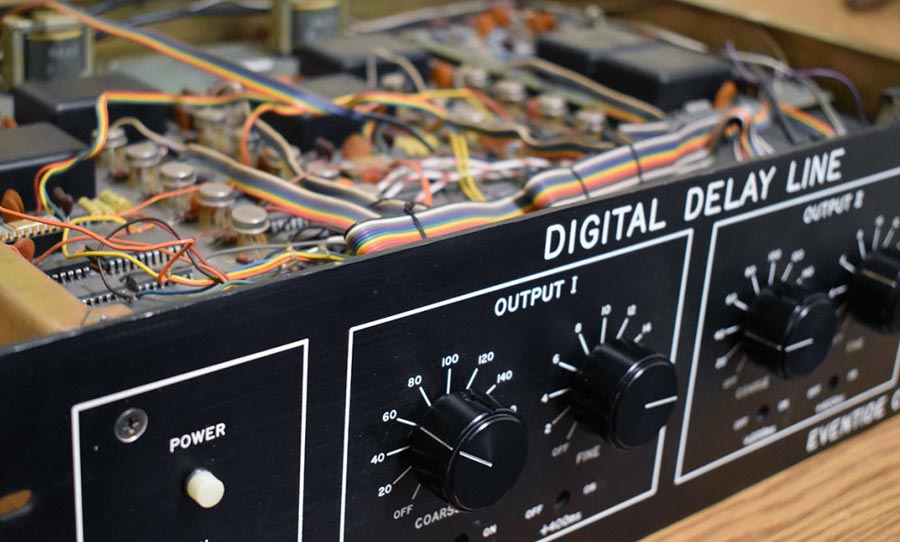

There were a couple of smaller options available by then, but for the most part, engineers were still creating delays using two tape machines. The longer the delay, the wider the machines had to be spread – not exactly feasible in every studio. Eventide’s solution was the DDL 1745 – the very first digital delay line.

A simple unit by today’s standards, it was nonetheless executed with elegance. An analog to digital converter accepted the input signal, then it was routed through shift registers to delay the signal, then outputted through a digital to analog converter. It was prohibitively expensive but it laid the groundwork for Eventide’s more sophisticated and successful units.

Perfect pitch

Agnello came upon the idea to combine delay with pitch-shifting. This led to the development of the H910 Harmonizer. It went beyond what you expect of modulation style effects like chorus, flange and phase, genuinely creating a sound unto itself. Long-time David Bowie producer Tony Visconti perhaps described it best: “It fucks with the fabric of time.”

Funnily enough, the 910’s main customers were TV studios. Late at night, TV stations used to play repeats of I Love Lucy, but sped up the tape so they could run more commercials. The Harmonizer was then used to bring Lucille Ball’s voice down in pitch. Definitely not the clientele that Eventide had in mind, but like other digital products of the era, the target market didn’t exist yet.

When the ’80s arrived, digital technology was more widespread and cheaper to obtain. The company again broke new ground with the SP2016, the first programmable digital effects unit. This new era of digital reverb gave engineers unprecedented options for sculpting ambience.

The SP2016 could also have algorithms loaded into it with ROMs that have additional software. This ‘plugin’ style of processing obviously took hold in the DAW world and it was also pivotal in the development of the H3000: the Ultra-Harmonizer.

The H3000 harnessed the power of digital signal processing (DSP) algorithms to create an outboard unit within even more flexibility than the SP2016. Since then, the H3000 has been reborn in many guises, including the recently released H9000, with its enormous library of sounds.

Naturally, Eventide has applied its software expertise to a range of plugins, bringing all their hardware classics and more into the DAW domain. It’s testament to their popularity in the studio that they still produce rackmounted products, despite the expense. Developing digital products for the studio before there was a market for it was risky, but it was a gamble that well and truly paid off.