Honest, raw and refined, Neil Young’s emotive fourth studio album, Harvest, was a fresh take on country-rock and to this day remains a classic. Here’s how it was made.

In the early 1970s, rock was getting heavier, glamorised or more progressive and complex. For a few, however, it was the stripped back and traditional sounds of folk and blues that still offered a medium for the rawest emotion. Neil Young‘s fourth studio album, Harvest is undoubtedly a classic.

A fresh take on country-rock, it became the best selling album in the US in 1972. The album launched Young into stardom, and the singles Old Man and Heart of Gold (his only number one) remain jukebox essentials to this day.

Thematically the album explores issues close to Young’s heart, and with a vibrant live feel, it is both honest and refined, and all-together intoxicatingly immersive. Let’s take a look at how it was recorded.

Sowing The Harvest Seeds

In 1971, the folk supergroup Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young went their separate ways. Young had already pursued a solo career, having enjoyed moderate success the previous year for his third studio album and commercial breakthrough, After the Gold Rush. He followed with an extensive solo acoustic tour and, in January of 1971, returned to his hometown, Toronto, to play a now legendary show at the Massey Hall.

In his prolific nature, Young had been constantly writing while on tour. Near the start of the show he told the audience, “I’ve written so many new ones that I can’t think of anything else to do with them other than sing them.” Needless to say, the punters did not protest. He proceeded to deliver his new songs to the awestruck spectators, a potent combination of the now-classics, Heart of Gold and Needle and the Damage Done, amongst others.

Within two weeks of the concert he laid down the first parts for these seminal tracks, and within a few short months Harvest was completed and released on Reprise Records in 1972.

Down to Nashville, Up to London

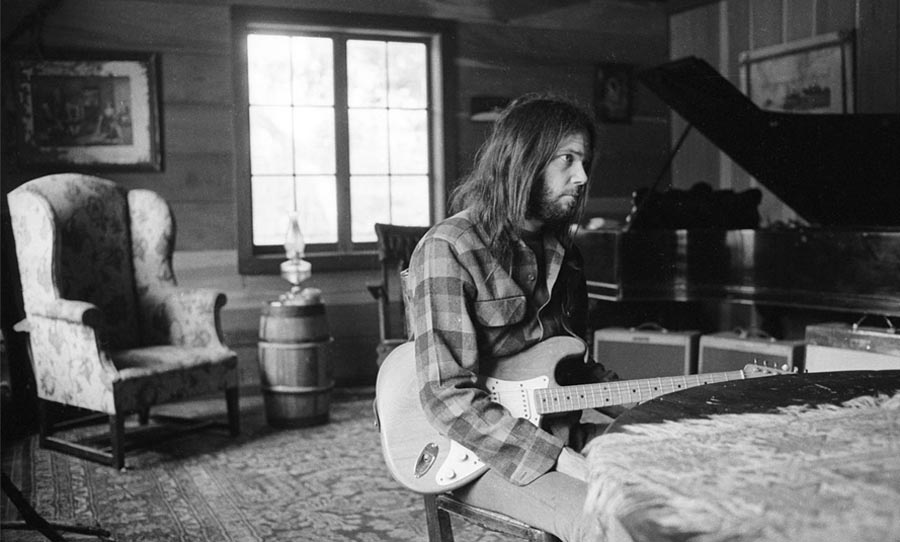

The sessions for Harvest were split into three separate stints across 1971, beginning spontaneously in Nashville while Young was tour. The majority of the electric guitar was recorded in a barn on his California ranch, before recording in London with the London Symphony Orchestra. Needle and the Damage Done however was a live take, lifted from his January 1971 performance at UCLA’s iconic Royce Hall.

Young arrived in Nashville in February 1971 to perform on a broadcast of the Johnny Cash Show, which also featured James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt. The producer Elliot Mazer, hosted an after party for the musicians, where he and Neil started talking.

He already had his bag full of new songs and had been considering a place to record his next album, so it didn’t take him much convincing when Mazer offered his newly furbished Quadrophonic Sound Studio. A converted Victorian-era house, the space was cosy and homey, utilising its living room for recording.

In terms of collaborators, Young already had people in mind and he made the decision to start straight away. He had heard of a group of local studio musicians, Area Code 615, who frequented Quadrophonic. Mazer recalled in BMI: “After dinner Neil said, ‘Hey, aren’t you the guys who have that Area Code 615 band?.’ Right there he asked if he could come down to Quad and do some work. All he needed was a small group of players, just bass, drums, and steel.”

Mazer scrambled to get the talent; he found the drummer Kenny Buttrey, bassist Tim Drummond and steel guitarist Ben Keith. The newly assembled group recorded live and laid the foundations for Old Man, Bad Fog Of Loneliness and Dance Dance Dance, the latter two not making the final cut. Taylor, who had stayed to watch the recording, contributed the twangy banjo overdubs on the former. The second session produced Heart of Gold; Neil had perfect chemistry with his new band and they completed it in just two takes.

“Kenny Buttrey and I made eye contact while listening, and we both raised a finger that said we knew it was going to be a No. 1 hit,” Mazer recalled. “Tim Drummond and Kenny played together so much that they just connected to each other. Teddy Irwin found some harmonics and rhythm chops, and Ben Keith just sailed through the song. We did one or two takes.”

James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt added harmonies over the master take. All in all Heart of Gold was recorded in less than two hours.

Young then recorded in London with the London Symphony Orchestra, laying down There’s a World and A Man Needs a Maid, while in town to perform his infamous Live At The BBC concert (above). The archival footage below shows Young working with the orchestra and producer Jack Nitzsche on a difficult take of A Man Needs a Maid.

“They definitely have to hear me. It’s obvious that they have to hear me—they were playing half a beat behind me all the way through the fucking thing,” says a frustrated Young.

Tools of the Trade

The warm surrounds of Quadrophonic Studios were fitted with a Quad Eight 20×8×16 console, and much of Harvest was recorded on this machine onto 2-inch 16-track Scotch 206 tape with no noise reduction.

No external effects were used apart from a 15 IPS tape slapback on a few tracks including Young’s voice. Vocals were recorded with a Neumann U87, with no compressors used, Mazer stating: “I hand-rode his voice, which meant I had to learn the song and anticipate his moves.”

Mazer made extensive use of a Neuman KM86 multi-pattern condenser microphone, which soaked up Young’s Martin D-45 – the guitar he used for all of the acoustic parts. The same mic was used on Teddy Irwin’s guitars, and as an overhead on Buttrey’s drums. The distinctive thumping kick used throughout the album was formed by removing the drum’s front head and heavily muffling it with a pillow, held in place intuitively with duct-tape. A Shure SM56 was used for the snare, and the hi-hats an AKG 224E.

Drummond’s bass was DI’d and Keith’s slide guitar was also captured by the Neumann U87. Due to close proximity and subsequent bleed, Young’s mics had to be considered as part of the drum sound during the session.

Rather than moving the vocal setup as far away as possible from the drums and using more mics exclusively, Mazer used fewer mics and tried to minimise the spillage in the close quarters. However, the presence of the room was essential to the album’s live feel – a key reason these Quadrophonic recordings sound so immersive. Similar techniques became essential in the later barn recordings.

More Barn

Young purchased his Californian ranch Broken Arrow in 1970. The thousand-acre property was paid for in cash following the commercial successes of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and After The Gold Rush. He had planned to set up a studio, however was held back due to touring and a debilitating back injury for which he required surgery.

It was here that Harvest’s electric songs were recorded, as well as a large part of the mixing. The Quadrophonic studio team – Keith, Buttrey and Drummond and Nitzche on piano, were recruited to the ranch in the following September, utilising a similar recording setup. For the sessions, Young purchased the same mixing desk as Quadrophonic studios, as well as JBL monitors, throwing together a makeshift studio within the confines of his home and one of the property’s barns.

“Neil’s studio wasn’t built yet, so we were set up in the living room of his house. He had just bought the same console we had at Quad — a Quad-8 fully discreet 24×16 — plus some JBL monitors, a couple of EMT plates, and some tape machines. While Neil was in the hospital having back surgery, I mixed the two London Symphony things and sometime later mixed the three electric tracks there as well,” said Mazer.

Mazer installed PA speakers in the barn to use as monitors rather than having the players use headphones, resulting in a lot of bleed between microphones. Although not technically perfect, Mazer and Young ended up liking the sound and kept the system. This added to the Mazer’s pursuit to capture not just the feeling of the live sound, but also the space of the barn, which was further reinforced with ambient room mics.

For these sessions, Young plugged in his beloved 1953 Gibson Les Paul, ‘Old Black’, usually run through a late 50s Fender Tweed Deluxe (5E3). He also used Gretch White Falcon for the solo on Words (Between the Lines of Age). A large component of his dirty guitar tone was the combination of humbuckers and his cranked Tweed Fender. This sound became the basis for some of his heavier works which followed, and eventually earnt him the title of ‘The Grungefather’.

The electric sessions produced the songs Alabama, Are You Ready For The Country and the album’s grand finale Words (Between the Lines and Age). Backing vocals were overdubbed by Young’s old bandmates Crosby, Still and Nash by Mazer in New York.

After the recording was finished, Graham Nash visited Young’s home studio at the sunny Californian ranch for a playback session, expecting a casual listening. “That’s not what Neil had in mind. He said, ‘Get into the rowboat.. we’re going out into the middle of the lake,'” said Nash in an interview with NPR.

Young and Mazer rigged up the PA system from the barn and house itself, and the eccentric duo proceeding to blast the early mix of Harvest out across the water. “I heard Harvest coming out of these two incredibly large loudspeakers, louder than hell. It was unbelievable.”

Lyrics and Themes of Harvest

Harvest deals with some complex issues, many that were close to Young’s heart. It is perhaps these intricate themes that make his individual performances on the album so sincere. In a short making-of documentary (see below) he stated:“I’m not sure that I could recreate that feeling. It has to do with how old I was, what was happening in the world, what I had just done, what I wanted to do next, who I was living with, who my friends were, what the weather was.”

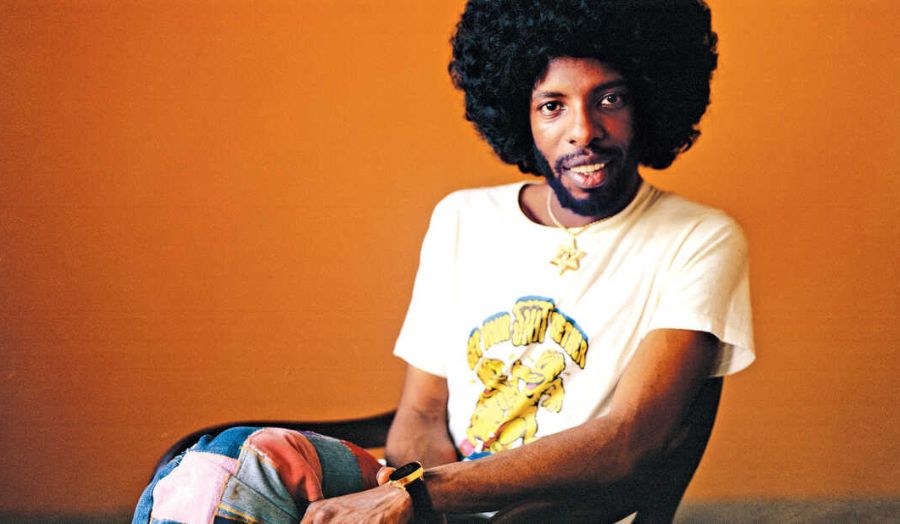

Perhaps the most famous of his stories lies in the melancholy lament, The Needle and the Damage Done, a song that depicts the debilitating heroin addictions of his good friend and Crazy Horse bandmate Danny Whitten, as well as Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s roadie, Bruce Berry. Both would eventually die of their addiction soon after the release of Harvest, answering the prophetic lyrics “Every Junkie’s like a setting sun.”

Alambama, a re-write of his previous album’s Southern Man, takes aim at the southern states’ history of socially ingrained racism and resistance to civil rights and social change. So effective was his message that southern rockers Lynyrd Skynyrd felt the need to include a rebuttal in their 1974 classic, Sweet Home Alabama: “Well I heard Mister Young sing about her, Well I heard old Neil put her down, Well, I hope Neil Young will remember, A southern man don’t need him around anyhow.”

A Man Needs a Maid is a haunting contemplation of a new romance. Some critics have pointed out the songs misogynistic undertones, while others have interpreted it as a song about Young’s insecurities, and feeling bare and afraid. At the time, he was approaching a new relationship, the song referencing his infatuation with the actress Carrie Snodgress. The two eventually became a couple and having a child together.

Cream of the Crop

Harvest launched Neil Young into international stardom, and he did not take it well. As well as disliking the fame, he withdrew into personal chaos: the chronic back-pain lingered, his new relationship with Snodgress was on the rocks, and their newborn son had suffered a brain aneurysm. Add the tragic death of his good friend Danny Whitten, and the limelight did not feel so sweet.

Young later stated that he would have hated himself if he made another Harvest, his subsequent albums On The Beach and Tonight’s the Night are comparatively much darker, heavier and musically raw. Instead of heading in the direction his label and fans expected, he defied all expectations and went down a different road and became an inspiration for punk and grunge alike.