The home studio is the dream for many musicians. Let’s explore the 4 essentials: microphone, audio interface, DAW and computer, monitors and headphones.

Recording your own musical projects in the comfort of your own home studio. Sounds like a snap right? In many ways, it really is. Digital technology has all but wiped out the comparatively labour intensive process of recording with analog tape (unless you want to, of course). Nowadays, it’s vital to understand four key links in the chain: microphone, audio interface, the DAW and computer, and finally, monitors and headphones.

Assuming you have the requisite ducks in a row, recording can be fluid, spontaneous and fun. But about those ducks — what are they, and how do you know what gear is right for you?

The following is for those curious about putting together their own home studio. Not just for simply recording basic ideas, but for getting the most out of every link in the chain, to get the best result possible.

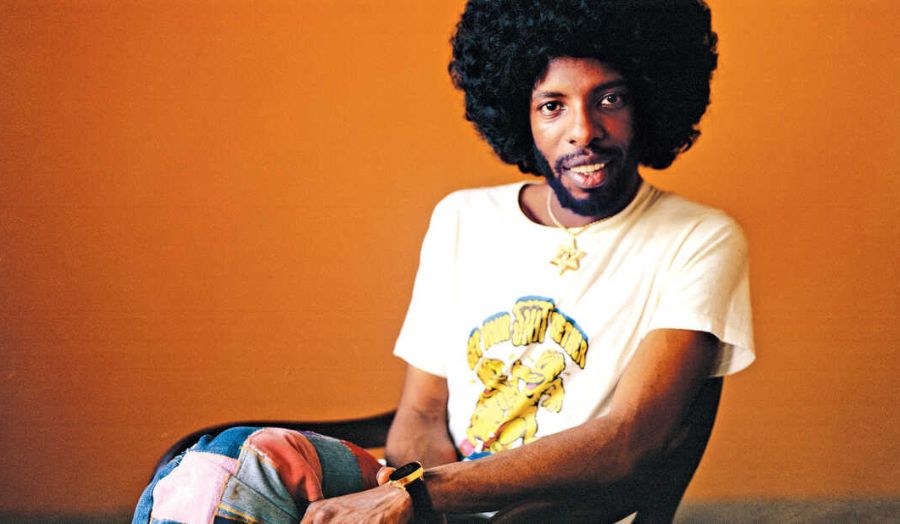

Step 1: microphone

In a home studio, sans soundproofing, the sound sources you’re most likely to record are going to be quiet. There might be some acoustic guitar, quiet percussion, but if you’re a songwriter, vocal miking is going to be crucial.

To the uninitiated, there are three main types of microphones: dynamic, condenser and ribbon.

Dynamic microphones tend to be cheaper, and are typically very robust. And even to non-experts, the shape of dynamic microphones like the Shure SM58 is unmistakable. Depending on the quality of the dynamic, they may not be suitable for the voice. For one thing, they are not particularly sensitive, so nuanced and delicate vocal performances don’t always translate well.

That’s not to say all dynamics aren’t sophisticated enough to handle vocal duties. The Sennheiser MD 441 and ElectroVoice RE20 are high-end vocal mics (with prices to match).

And sometimes, the aforementioned lack of sensitivity can be a positive when recording a vocal alongside another instrument. The Shure SM7B, for example, is specially designed for broadcasting, with features that reduce plosive sounds (distracting air blasts resulting from B and P words) and effectively reject off-axis sounds (like an acoustic guitar or piano).

The most common type of microphone for capturing vocals in a studio setting is the condenser. Condensers feature a diaphragm fixed to a backplate. The sound pressure from a voice vibrates the diaphragm. This arrangement makes for a much more detailed picture of the sound source when compared with a dynamic. Therefore, condensers are routinely favoured for recording the ever so subtle nuances of the human voice.

They also excel at reproducing other delicate sounds. Recording the acoustic guitar isn’t outside the realm of possibility in a home studio and it can often benefit from the condenser’s characteristically refined character.

The price tags attached to condenser microphones can also vary wildly. The best of the best in this family of microphones will soar into the many thousands of dollars, (see the Neumann U 47 for example) but they can also be absurdly cheap (and sometimes nasty).

Ribbon microphones are the rarest of the three categories and possibly the least suited to tracking vocals. Compared to dynamics and condensers, their character is smoother, with more of a tendency to accentuate lower frequencies — which doesn’t make for increased vocal intelligibility.

If you are in the market for a more ‘vintage’ character, ribbons have it in spades. Their extended reach into the lower end of the spectrum, combined with their absence of a noticeable upper-frequency peak makes for a rich and refined tone.

Modern ribbons like the Royer R121 are also typically more robust than their vintage counterparts. Some ribbons, the Audio-Technica 4080 for example, actually utilise phantom power to increase their output level.

With all microphones (especially your vocal mic of choice), a rigorous test drive is recommended. The good news is that it’s easy to do! Simply run the mic through a preamp, and monitor your voice through headphones (headphones are really handy in this case because you’ll be able to hear how microphone translates the finer details of your voice).

Condensers will make your voice sound considerably ‘brighter’ by accentuating the high frequencies. The benefit of this will be the detail and intelligibility that it offers in the context of a mix.

Dynamics will more subtly boost the top end and the boost won’t reach as far into the high frequencies. Detail and sensitivity are somewhat sacrificed with this type of microphone, but that might be just the thing you’re looking for, especially for a more aggressive vocal delivery.

Ribbons have less of a high-end presence and a richer bottom end. So, less ‘cut-through’ in the mix, but more warmth and intimacy.

With all this talk of vocal miking, it’s easy to neglect other sounds. Every engineer will have their own opinion on which microphone is the most versatile, but it could be argued that testing it on a source as personal to you as your own voice will give you the best understanding of a mic’s capabilities.

Whichever your choice, listening to your voice (and more sounds, if you can manage it) through at least one microphone of each of the three categories will help you make an informed decision about which type will be best for your home studio.

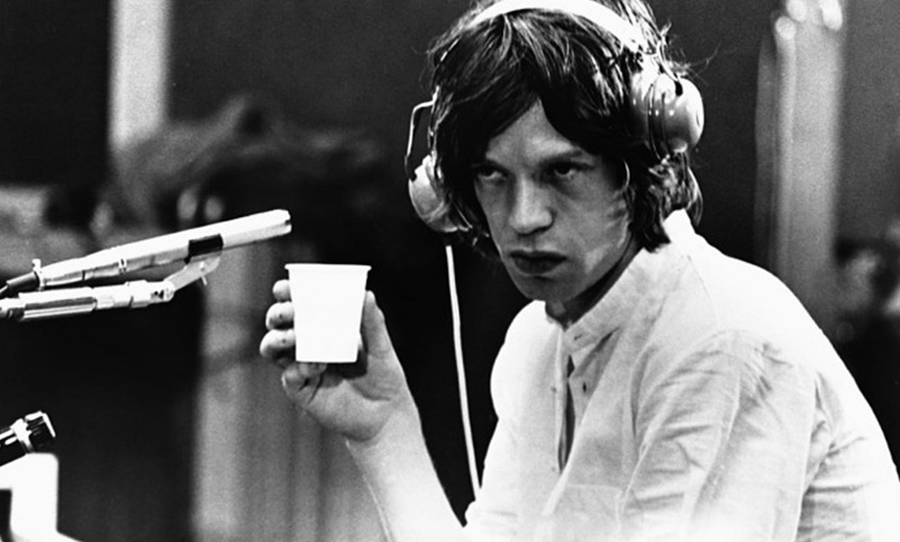

Step 2: audio interface

In a DAW-based home studio, the audio interface has replaced the console. It’s the hub through which all sounds are routed, so let’s explore the ins and outs.

The audio interface can be a simple affair, or exceedingly complex. If your digital audio workstation (DAW for short) software is the brain of your setup, then the audio interface is its beating heart, pumping signal throughout the studio’s nervous system.

Aside from being a way to simply hook things up, the interface can add a distinct personality to microphone signals via preamps, provide virtual guitar amplification, send MIDI signal to and from pieces of hardware and more. While the audio interface can facilitate multiple roles in the project studio, but its essential purpose is to convert the analog audio signal to a digital audio signal.

When you make a noise in front of a microphone, the movement of the diaphragm (or the ribbon) creates voltage. The voltage is carried down the microphone cable to the audio interface, where the analog to digital converter transforms the electrical charge into the ones and zeros of digital speak. This means that it can be recorded by your DAW.

The interface will then do the job of converting the digital signal back to an analog one. This conversion stage is required for you to monitor the sound through speakers or headphones. Therefore, interfaces are typically labelled ADA (analog-digital-analog) converters.

Many an hour can be lost in audio forums discussing the quality of converters. If you have a well-trained ear and a listening environment of exceptional fidelity, the difference between different brands of converters will be more obvious. In a project studio context, however, other factors are likely to make a bigger contribution to the success of a recording.

Microphone preamps add gain to a weak microphone signal — a non-negotiable link in the chain when recording with microphones. Though its job is a simple one, preamps undoubtedly colour the microphone signal. Professional sound engineers spend entire careers concocting specific combinations of microphones and preamps to suit the individual character of a performer. Needless to say, they’re important.

Many standalone analog preamps that take their design cues directly from hitmaking consoles have been developed. But for anyone without deep pockets, or who isn’t working in the field professionally, these little gems can be prohibitively expensive.

Many audio interface manufacturers prize clarity above all other qualities of sound. Others laud to the analog-like qualities of their preamps’ character. For example, Universal Audio has gone to great lengths to achieve the same character as original vintage hardware in their Apollo series.

Audient has taken a different route, inserting a real valve into its guitar-friendly interface, Sono. Whereas Apogee is famous for delivering a pristine, unblemished signal path in its interface preamps.

Are too many channels ever enough? Yes, having an abundance of channels to plug in enough mics to record an entire drum kit, electric guitars, bass, keys and vocals is without doubt, awesome. The more channels you have though, the pricier it gets.

Now, this can be a conundrum. You might only need one or two channels now, but what if your home studio expands? You might not want to track a full drum kit in your project studio, but you might want to incorporate a host of synths, drum machines and other electronic elements into your productions.

Also worthy of consideration are outputs. Every audio interface will have at least one set of stereo outputs for monitoring. Some will have main monitor outputs, plus a headphone output. Some will also have extra line outputs. When do these come in handy?

Many engineers prefer to have multiple sets of monitors for getting a different perspective on mixes, which require additional outputs. You’ll need extra outputs for running external effects or setting up a reamp channel. Depending on your DAW, you can even create a surround sound system. In other words, having more outputs can facilitate the expansion of your sound palette.

As with microphones, there is a lot to consider when looking at an audio interface. The number of available options is mind-boggling, so it’s helpful to keep your primary objective (making music!) in mind.

The best audio interfaces facilitate a fluid production workflow, are dependable, and sink seamlessly into your system. So listen deeply, find out more about mic preamps and figure out what gear you want to have plugged into the system when inspiration strikes.

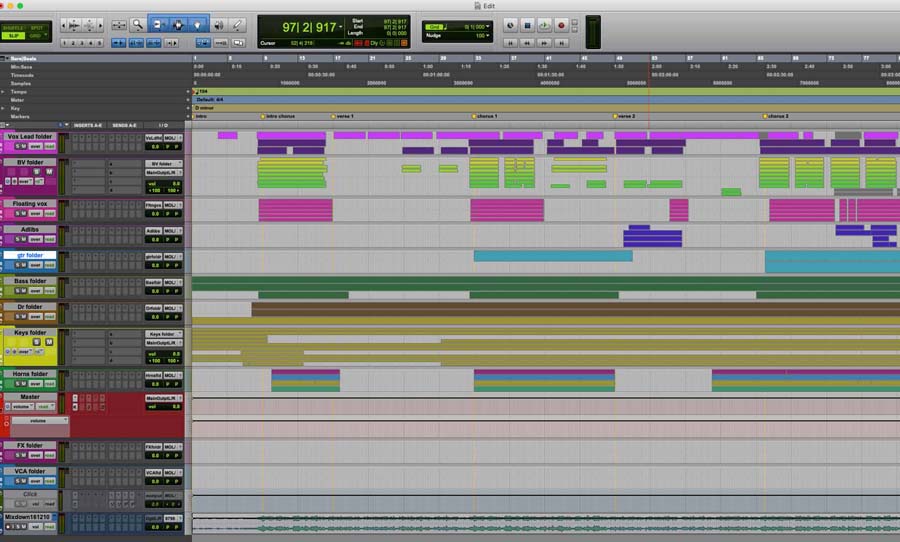

Step 3: DAW and the computer

Beyond the microphone and audio interface, the path toward an efficient home studio becomes less clear. Waiting beyond these two pieces of relatively straightforward hardware is the software world — the computer and the digital audio workstation (more commonly known as the DAW).

Why has it gotten murkier? Well, this is the point where opinions become more vociferous, tribal battle lines are starkly drawn. There is simply so much choice when it comes to facilitating the production of music ‘in the box’ that almost everyone will have a different opinion.

There’s also a comparatively steep learning curve when confronted with the DAW. Options for sculpting sound in the software realm are almost endless, so a degree of patience is required if you’re new to this territory.

Another piece of ubiquitous, new age audio jargon is ‘workflow’. This is a byword for efficiency in music production — but efficiency doesn’t really do it justice. There is a myriad of directions in which you can take a song in the midst of production; having healthy workflow means that editing, recording, performance and composing can all take can all be facilitated without encountering too many frustrating technical hurdles. The computer and the DAW should work hand in hand, providing an environment that inspires creativity.

Few topics get audio types hot under the collar like computers. The whole PC vs Mac debate is interminable, and in some ways, driven more by grievances with company philosophies and tribal affiliations, rather than performance. The key components that actually affect performance in a music production context are the computer’s central processing unit (CPU), storage and RAM.

The CPU is a chip that can be found on the computer’s motherboard and controls all of its functions. While there is a wealth of detailed information and opinion available to you on the topic of the best CPU for audio, it’s best to get a grip on the basics.

CPUs are made of cores — the more CPU cores you have available, the more simultaneous tasks your computer can perform. This will improve the smoothness and speed of your computer when working with audio, virtual instruments, plugins and so on.

If you’re aiming to create complex sound worlds that rely heavily on high fidelity plugins and numerous virtual instruments, a quad-core CPU will probably be a minimum. Hexa-core and upwards will be more desirable for running mixes with high channel counts.

Hard drives are also important for getting a smooth and speedy response from your computer. Hard disk drives (HDD) are comparatively older technology; Solid-state drives (SSD) are definitely in vogue for audio production.

They are faster, with no moving parts and less prone to shock damage. They can be, however, quite pricey. Therefore, you’ll need to do the maths on how much storage you’ll actually need to run your sessions efficiently. A good compromise could involve running your projects off a smaller solid-state drive while backing up and archiving them with a larger HDD.

Potentially of importance in your computer is RAM (random access memory). RAM chips store data temporarily, which enables faster access.

If you were doing a DIY building project, it would be smarter to go to your shed just once, grab all the tools you need and have them within reach on your workbench, allowing you to work quickly and economically. RAM works like this.

Therefore, if you had masses of data that you needed for a music project — for example, a large orchestral sample library — having more RAM would be beneficial. This might require you to have 16 or maybe even 32 GB of RAM on hand. Whereas for smaller projects, you might only need 4 to 8 GB.

Now that you’ve researched and digested a dizzying array of technical computer specs, it’s time to get creative. The DAW is the software that records audio, plays hosts to numerous virtual instruments, facilitates the editing of audio, MIDI and a plethora of other music production tasks.

Choosing the right one for your own needs is inevitably a deeply personal decision. And in an effort to distinguish themselves in an increasingly crowded market, each offers unique features that may or may not speak to your ideals when it comes to music production.

The DAW came to prominence in the professional studio system in the 1990s. With decades of incremental improvements, the DAW is well and truly a mature technology.

Pro Tools has cemented itself as the industry standard and is still highly sought after for its no-fuss recording and audio editing capabilities. Logic has also evolved to be a classic allrounder, though only available on Mac OS.

Programs like FL Studio, Ableton Live and later, Reason Studios have taken an alternative approach to production, prioritising user interfaces that encourage modular building blocks, going on to be hugely influential in shaping electronic music.

In recent years, REAPER, Bitwig and an increasing number of DAWs based on mobile platforms have further democratised software-based music production. And a number of programs like Garageband, Audacity and Soundtrap have little to no cost involved, so it’s easier than ever to start your journey without a significant cash outlay.

Translating the analog into digital and getting your sounds into the box is a tremendously empowering experience. Cutting edge computer power has fostered the growth of incredibly powerful tools for producing and manipulating audio. While DAWs are endlessly innovating, creating ever more intuitive ways for us to make music. In short, it’s a great time to be alive!

Arming yourself with a basic knowledge of the relevant specs and experimenting with a range of DAWs can help all elements of your home studio to work together in harmony.

Step 4: monitors and headphones

How you listen to and analyse your work can make or break your studio production. So let’s dive into the world of monitors and headphones.

Listening back to your work with a critical ear is an essential link in the production chain. To judge the audio without prejudice, and to hear the ‘truth’ of your mixes, you’ll need to get the right tools for the job.

Monitoring isn’t necessarily about enjoyment or listening to things as loudly as possible. It’s all about making decisions. If your listening environment can reveal the strengths and weaknesses of your productions, you’ll at least have the opportunity to address them.

If you plan on mixing and mastering your tracks in your home studio, then you need to be doubly aware of your monitoring capability. Mixing and mastering require a sharp focus on different areas of the frequency spectrum. Your monitoring setup will play a critical role in determining whether you can identify problem areas and create professional-sounding finished products.

Monitoring is studio speak for listening. In a traditional recording studio, monitoring takes place in the ‘control room’. This room is acoustically separated from the performers in the ‘live room’, meaning that what you hear is a cleanly separated version of the live performance, through the microphones that are capturing the sound of the instruments.

A control room might have multiple sets of speakers that are designed to show the mix from different perspectives. Nearfield monitors are smaller and designed to be positioned close to the listener. Farfield monitors are larger, designed to be further away, and are sometimes flushmounted within the walls of the control room.

Nearfield monitors will highlight the mid-range and upper-frequencies in the mix. The mid-range is particularly audible at lower volumes (see the Fletcher-Munson curves), therefore, nearfields play an important role in analysing the mid-range of the spectrum.

The Yamaha NS-10 for example, has a legendary reputation in this role, enjoying near-ubiquity in pro studio control rooms from the ’80s onwards. Even superstar mixer Chris Lord-Alge and Avantone have codesigned their own version of the humble box — not bad for a cheap and primitive monitor.

So why mix on such apparently deficient device? Everyday consumers of music are not listening through perfectly balanced hi-fi systems. Think about the multitude of highly compromised environments where people listen to music — the car, the tinny Bluetooth speaker, the earbuds and so on. Small monitors are useful in creating mixes that translate well across multiple environments.

So why the need for big, farfield monitors at all? These types of monitors can handle more volume and have the physical proportions to expose frequencies at the more extreme ends of the spectrum — a must for spacious control rooms and mastering suites that routinely put out commercial competitive mixes.

This type of monitor, however, would not be best suited to a small, acoustically untreated home studio. To hear thumping bottom end frequencies, crystal clear high end and pinpoint stereo imaging with any accuracy, you’ll need the appropriate acoustic treatment. This can be quite expensive and incredibly difficult to achieve in a small, cube-shaped room.

Headphones also play a critical role in a holistic monitoring rig. They are excellent tools for picking up the finer details in a busy arrangement and monitoring while recording. There are, however, a few key specs to look out for that will help you pick the right pair of cans for the job.

If you’re looking to use headphones for monitoring while recording, a pair of closed-back cans are more suitable. Depending on the quality of the individual pair, they can do a great job of creating a seal around the ears, giving you the best possible opportunity to monitor accurately in a noisy recording environment. Considering that your project studio is likely to be the live room and control room, this kind of headphone should be a worthy asset.

Open-backed headphones have a different sound and a different purpose. Owing to their design, this type of headphone reflects the frequency spectrum with more accuracy — less prone to boomy bottom and a more detailed in the high frequencies. They’re also more comfortable to wear for long periods of time. These factors combine to make a better choice for mixing.

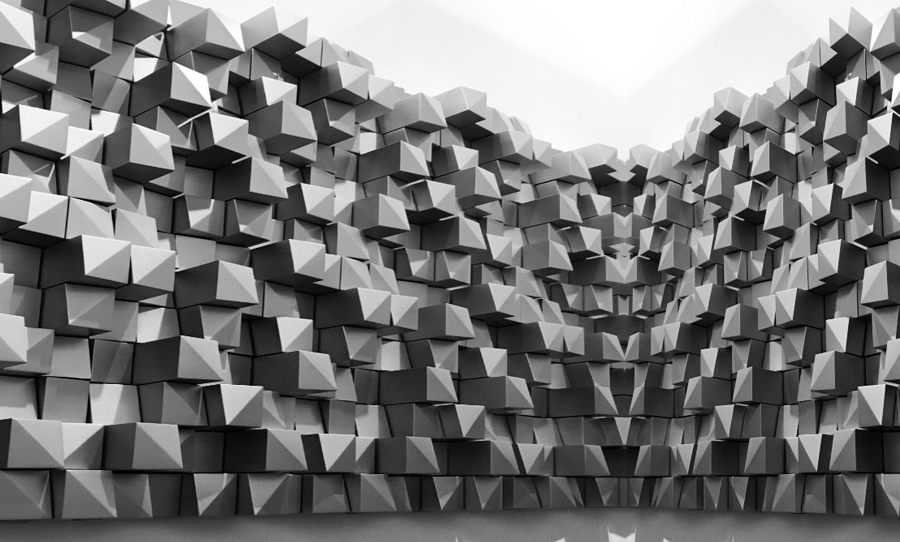

The acoustic treatment and physical dimensions of your space are arguably even more significant than any other element in the monitoring equation. The two main techniques in acoustic treatment —absorption and diffusion — can go a long way to ensuring that what you’re hearing is actually happening.

We can easily be fooled by listening in a room with substandard acoustics. Reflections can distort our perception of the stereo image, room modes can cancel out bottom end frequencies, awkward resonances can cause certain frequencies to spike. In other words, there is many a pitfall when it comes to finding a room that has reliable acoustics.

This is where absorption and diffusion come into the picture. Absorptive materials are designed to soak up sound and keep your mixing position clear of reflections. Absorbing higher frequencies can be achieved quite easily, usually with materials like foam or acoustic fibreglass.

Without going to into too much detail about room modes or standing waves, bottom end frequencies present a much bigger challenge, especially in small rooms. Short of designing and building an entirely new space, these reflections can be somewhat mitigated by effective bass trapping.

Diffusive surfaces scatter the sound, creating a natural dispersion of high frequencies. Diffusion helps to create a more natural listening environment but still controls echoes in the room. Diffusion panels are hard irregular surfaces, usually made from timber blocks of random lengths.

Listening critically is difficult at the best of times and even harder without the tools to do so. There is a massive diversity of studio monitors, with a plethora of manufacturers clamouring for your hard-earned dollars.

The same can be said for headphones. A wide selection of products with a range of different price points is more readily available than ever. But with such a dizzying array of options, it might serve you best to scrutinise the acoustics of your room and plan accordingly.

For example, should you buy expensive monitors without addressing the reflective aspects of your room? Is it better to invest in good quality open-backed headphones if you need a portable mixing rig? All worthwhile questions in the pursuit of the best possible result from your project studio productions.

As you can see from the thousands of words expended on this very article. There’s much to consider when planning your home studio. If it ever gets overwhelming, it pays to remember that essentially, the signal chain is quite linear: sound goes into the microphone, passes through the audio interface, is tweaked within your DAW and is sent to your monitors for you to listen to. Making the appropriate decisions at these crucial points in the chain will help you to create a happy and healthy home studio.