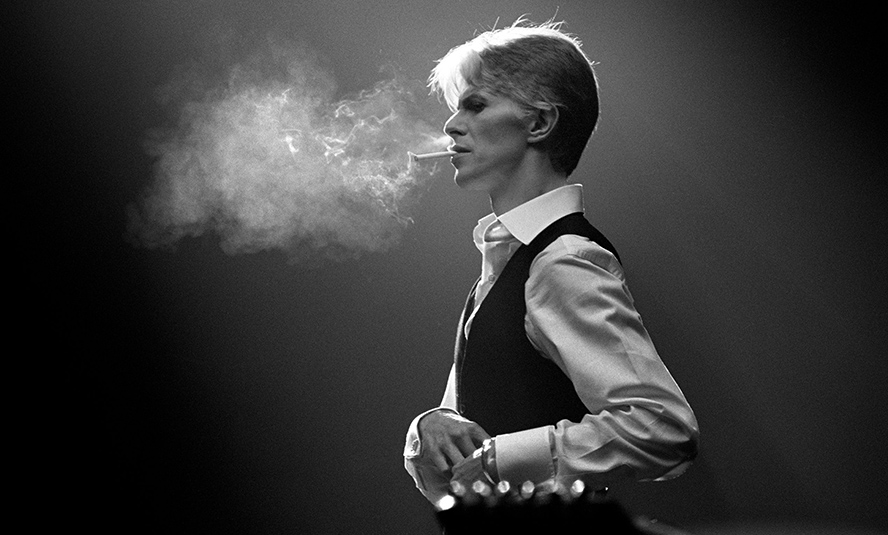

David Bowie is often described as a chameleon both in a musical and aesthetic sense. From his cast of characters and alter egos – Ziggy Stardust, the Thin White Duke – to his far-ranging musical exploits (such as the Philly soul aesthetic of Young Americans, or the 80s pop sheen of Let’s Dance) Bowie was truly a jack of all trades.

While this might seem like the beginning of yet another retrospective on the work of Bowie, it’s actually an in-depth look into the record that served as the precursor to the ‘Berlin Trilogy’ (Low, Lodger and Heroes) – Station to Station. Most people would be familiar with the album’s hit Golden Years, but there’s so much more to explore, with elements of krautrock and ambient music and foreshadows Bowie’s later collaboration with Brian Eno.

Tying together the glam and funk elements of his earlier work and the electronic excess that would follow, Station to Station was David Bowie finding his skin and shedding it at the same time.

For the production of Station to Station, David Bowie enlisted Harry Maslin. The two had collaborated together on Young Americans, a relationship which yielded hits in the form of the album’s title track and Fame. And although Bowie’s drug-addled mental state of the period was fragile at best, with Maslin’s help and predilection for hard-hitting, slick funk grooves, the record came together cohesively in a frenzied blitz of creative freedom and surprising clarity of vision.

Tracked at Los Angeles’ now-defunct Cherokee studios, the album’s title track is the longest cut out of his entire discography, consisting of two halves. It opens with a swirling vortex of a train that shuffles between your speakers, right to left, layered with feedback from guitarist Carlos Alomar (likely played on an Alembic axe that he was partial to), and a trip into the occult courtesy of a Moog synth played by Bowie.

It’s in this disjointed opening that we are introduced to The Thin White Duke – a manic, cocaine-fuelled aristocrat character with interest in satanic imagery.

While Station To Station contains elements of Kraftwerkian experimentation, ambient sounds and proto-punk crunch, its personality shifts at the 5 minute mark, leaping from the lethargic, drug-addled introduction into a disco strut with a callback to the ‘plastic soul’ featured on Young Americans, but with strained vocals and an air of aristocratic pomp and confusion.

This is evident when Bowie yelps “It’s not the side effects of the cocaine/I’m thinking that it must be love”. The song pushes forward with percussion and a guitar tones that throws the listener around, with allusions towards the Berlin Trilogy in the quote: ‘The European Cannon is here!’

Where Station To Station foreshadows the future for Bowie, the album’s most familiar cut, Golden Years, represents an evolution of a style first heard on Young Americans – a radio friendly track with a snappy guitar and a style redolent of 1970s soul paradigm and punctuated by funk undertones.

The song is tied together, however, with the use of bass as the primary musical element. The guitar work on Golden Years is also worthy of including here, with its innovative application of a Mu-Tron Bi-Phase that sits in the background amongst the hand claps and the bass.

While the album’s most famous track has a decidedly upbeat tone, both lyrically and musically, the last track on side one underlines the Kraftwerk-meets-space rock aesthetic.

Word on a Wing opens with a piano and a psychedelic guitar punctuated with a healthy dose of reverb. This, combined with a crisp, dry drum sound (panned erratically) and lyrics pleading for forgiveness help inject the song a tone of repentance, underpinned by the question “Does my prayer fit in with your scheme of things?”

TVC15, opens with a piano (courtesy of E-Street band member Roy Bittan) reminiscent of music hall songs of the early 1900s, set against Alomar’s guitar strangled by a wall of fuzz. The track stands out as the album’s thematic black sheep, with its connection coming through the film The Man Who Fell to Earth (starring Bowie) that was released just before he started working on Station to Station.

This genre-bending in the context of Station to Station’s cocaine tinged madness continues with Stay – a guitar-driven track with percussion that wouldn’t be out of place in a 70s breakbeat. Alomar’s guitar shines here, with glam rock sensibilities, and an almost bluesy crunch to it. The sci-fi inflected Moog lends itself to underwriting the introduction of the track, which provides a psychedelic edge to the whole production.

At a total of six songs, Station to Station is short, but incredibly nuanced – each track provides its own sonic tableau. This is evermore evident on album closer, Wild is the Wind – a cover of a standard written by Dimitri Tiomkin and Ned Washington, and originally recorded and released by Johnny Mathis. Bowie’s version was inspired by Nina Simone’s interpretation of the track, which featured on her album of the same name from 1966. Interestingly, from a musical standpoint, it is driven forward by an acoustic guitar – a marked departure from the manic, electric ferocity of the preceding tracks.

Wild is the Wind, likewise with the album itself, is very much of its time, and its somber mood is analogous to a comedown from the madness of a drug-fuelled rush that the rest of the album provides.

For Bowie, it seems as though 1976 was a transitional year; this is reflected on Station to Station. Acting as a bridge between the soul of Young Americans and the intensity of his Berlin period, the album was recorded in a paranoid, drug-fuelled ten day burst in Los Angeles. It’s a city that Bowie absolutely detested, and later he described the whole work – and his character of the Thin White Duke – as “devoid of spirit.”

Musically, it was a wedge for Bowie’s experience from the 1970s with influences of glam rock and soul shining through the colder mechanical sounds that emerge throughout, as well as the innovative, albeit subtle use of synthesisers.

While it may not be his most musically accessible album (save for Golden Years), Station to Station says prodigious things about how the musical experimentations of the 1970s came to influence Bowie. The record looked toward the subsequent electronic revolution of the second half of the decade and beyond, while paying homage to what had come before.