The sitar has had an incredible history from medieval India to the cultural revolution of the ’60s, with a voice in music as unique as any fingerprint.

While the sitar has been around for roughly 400 years, it didn’t make the foray into Western music until the music of Ravi Shankar came to prominence. One fated day, George Harrison picked up the instrument on a film set and ever since the psychedelic sixties, minds and ears were open to the East.

Along with embracing their mind-expanding philosophies, food culture, and religious beliefs, many open-minded Westerners widely accepted the sitar in popular music thanks to a handful of adventurous rockers from a formative decade of musical exploration. Today the sitar is synonymous with all things psychedelic in rock music.

Raga roots

According to various sources, the sitar was invented by Amir Khusrow, a famous Sufi inventor, poet, and pioneer of Qawaali music. Typically measuring around 1.2 metres in length the sitar has a deep pear-shaped gourd body and is a member of the lute family. It has 20 movable frets and 18-20 strings – a combination of melody and droning strings, giving the instrument its iconic sound.

Adapted from the long-necked lutes taken to India from Central Asia, the sitar flourished as a courtly instrument in the 16th and 17th centuries becoming the dominant instrument if Hindustani music. Today there reigns two dominant schools of sitar music in India: that of Vilayat Khan and Ravi Shankar.

The West meets the East

‘The Godfather of World Music’, Ravi Shankar played a critical role in popularising sitar music in the West and was the original teacher and mentor of George Harrison. He was born in Vanarasi, in 1920, a place described by Mark Twain as, “older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend and look[ing] twice as old as all of them put together.”

The scion of an erudite Bengali Brahmin family, Ravi Shankar began travelling to Paris at age 10 with his brother’s dance troupe, studying at Parisian schools, and absorbing the music and dances of his culture as well as those of the West.

In 1934, Shankar met guru and multi-instrumentalist Allauddin Khan, who became his musical and spiritual guide for the next 10 years. Recalling his tuition under Khan, whom he called ‘Baba’, Shankar said, “One morning, in Brussels, I brought him to a cathedral where the choir was singing. The moment we entered, I could see he was in a strange mood.”

“The cathedral had a huge statue of the Virgin Mary. Baba went towards that statue and started howling like a child: ‘Ma, Ma’ (mother, mother), with tears flowing freely. We had to drag him out. Learning under Baba was a double whammy—the whole tradition behind him, plus his own religious experience.”

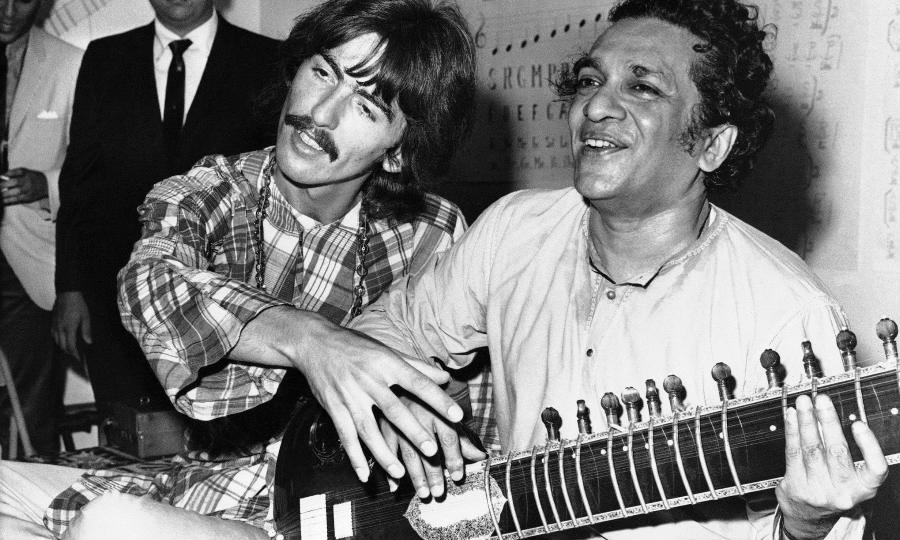

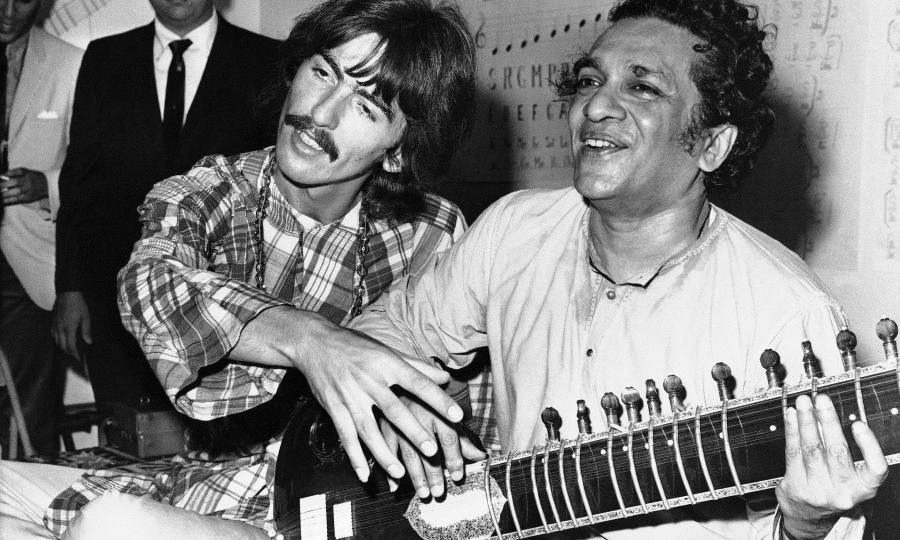

The open-mindedness of his mentor was a quality Shankar embodied throughout his career, becoming an ambassador for Indian music to the Western world. In 1966, Shankar befriended George Harrison and shot to international fame.

Raga rock

In 1965, someone nonchalantly decided to decorate the set for the Beatles’ film Help! with a sitar. In between takes, George Harrison was drawn by its Eastern mysticism and decided to pick it up. Lost in its labyrinth of strings George was perplexed, and, with his interest piqued, set out in search of a teacher.

What the set designer doesn’t know is they unequivocally changed popular music forever – if not history.

One year later a friendship blossomed between Harrison and Shankar, and George quickly became adept with the instrument. At this time Harrison had already recorded the famous Norweigan Wood, though was soon embarrassed after meeting Shankar, realising the ineptness of his own training.

Expressing great interest and humility regarding his knowledge of the holy instrument, Shankar agreed to train him. Meeting twice a week, the veteran maestro soon realised it would take great practice and patience for George to become a proper sitarist. Harrison was also unaware of basic etiquette in Hindustani classical music. He once horrified his teacher by casually stepping over his sitar to answer the phone and promptly got a sharp whack on his leg for not showing enough respect for his instrument – a fundamental creed of all Indian musicians.

George then went to India for six weeks to train under the tutelage of Ravi Shankar, however, the weight of his undertaking soon became apparent. The basic training period of an Indian musician is five years of eight hours’ daily practice and a further fifteen years before a player is considered up to scratch.

Indian musicians view their role as a performer as a sacred task. This devotion approach to their holy instrument starkly contrasted the casual approach of Western pop music.

“Ravi was my link into the Vedic world,” George recalls of their karmic connection. “Ravi plugged me into the whole of reality. I mean, I met Elvis—Elvis impressed me when I was a kid, and impressed me when I met him because of the buzz of meeting Elvis, but you couldn’t later on go round to him and say, ‘Elvis, what’s happening in the universe?”

By the time Sgt. Peppers rolled around Harrison had found his own voice 0n the sitar with enough technique to express himself freely. Within You, Without You remains The Beatles most defining moment of musical mosaicism embracing both Eastern sounds and philosophies, and inspiring innumerable musicians since.

Other notable ’60s sitar users are The Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones (who actually picked it up before Harrison) on Paint It Black, with other prominent examples being Tomorrow’s Real Life Permanent Dream, Traffic’s Paper Sun, The Monkees on This Just Doesn’t Seem to be My Day, and later by Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Hillel Slovak on Behind The Sun.

Modern Sitar

Japanese psychedelic rock band Kikagaku Moyo are renowned for crafting jam-heavy fuzzed-out sets, achieving international success through the electrifying of the sitar. After training in traditional piano for many years bandmember Ryu left Japan to study the art of sitar in India for 10 years and is still refining his talents.

For an instrument that is typically acoustic, Ryu uses lace sensor pickups – which utilise magnets instead of coils – before running the signal through a series of vintage effects to create a distinguishable, and extremely psychedelic sound in their lengthy mixed jams.

Ryu’s touring pedal chain consists of (in order) Vox V847wah, Ibanez Tubescreamer TS9, Third Stone Venus in Fuzz, Boss Equaliser, Boss DD-6 Delay, Digitech Supernatural Reverb, Memory Toy.

For a completely mesmerising, modern take on the sitar, there are few better than Kikagaku Moyo. This band, alongside many others, continue to reimagine the sonic limits of this ancient instrument.