Few industries are beset with urban myths like popular music. People who are actively involved devote an inordinate amount of brain power to the question of how to make a crust in the biz – those fortunate enough to make a living need to have hawk-like vigilance to keep the good times rollin’.

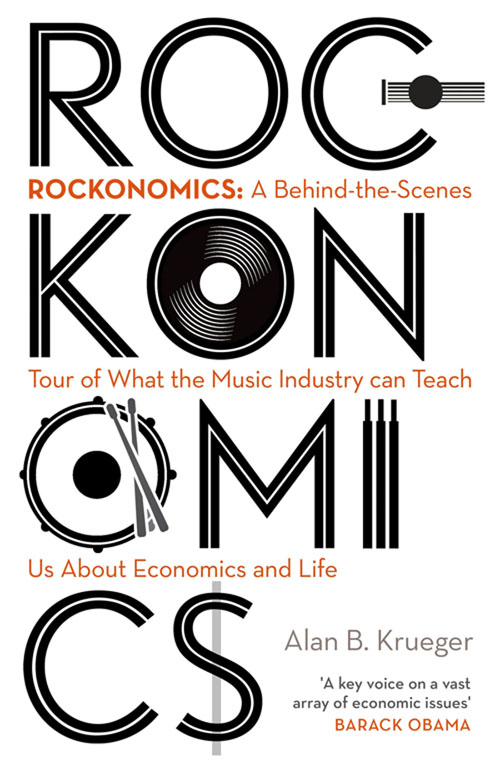

So when voice speaks with such authority, and is so piercing with clarity, it’s best to pay heed. The voice belongs to the late Alan B. Krueger. He was a Princeton professor and leading economic adviser to Barack Obama. Rockonomics is his analysis of economic trends in the music industry and how they’re reflected in the wider financial landscape.

It cuts through some of the more opaque elements of the modern music industry, dispels tall tales and presents us with some genuinely surprising statistics.

Rockonomics is a non-stop tour of the facts figures behind the music business. Alan B. Krueger explains the economic truth with wit and razor-sharp logic.

Importantly, while there are some retrospective elements to Krueger’s investigation, the focus is decidedly on the present trends and future predictions. The seven keys to Rockonomics are, however, still based on some well-established pillars of economic theory. Supply and demand, scale and the cost of doing business loom large.

Yet Krueger’s findings do throw up anomalies that seem to be idiosyncratic, if not unique, to music. The power of luck and price discrimination (a practice that Taylor Swift in particular has made the most of) are prominent. Perhaps the factor most particular to music is what Krueger calls the “Bowie Theory.” To explain it, the author takes a quote from the Thin White Duke himself:

“Music itself is going to become like running water or electricity…. You’d better be prepared for doing a lot of touring because that’s really the only unique situation that’s going to be left.”

This highlights one of the key building blocks for economic sustainability in music: the actual recorded product is likely to only form a miniscule proportion of a musician’s income (even if you’re wildly successful). Touring, merchandise and an array of what Krueger labels complementarities are how musicians can really bring home the bacon.

Lastly in Krueger’s seven keys is the observation that money isn’t everything in the music business. Music is a compliment to emotionally significant occasions almost uniformly around the world. Musicians pursue a life in music for reasons of passion, often against the odds.

Despite the near ubiquity of music in our everyday lives, one of many reality checks that Krueger offers, helps us put the music industry in perspective. He states that:

“No matter how you cut it, economically speaking, music is a relatively small industry. Global music spending in 2017 was only $50 billion, or 0.06 percent of world GDP.”

Far from being a doom and gloom story though, Krueger also points out that there is potential for future growth, especially in streaming. Backed by the statistics, Krueger makes the case that:

“Streaming is having a revolutionary effect on music sales. After fifteen years of decline or stagnation, revenue from recorded music finally began to increase in 2016. And the signs are that this upward trend will continue for some time.”

So, while the digitisation of the recorded medium has had a seismic impact on the industry – the prevalence and convenience of streaming means that there are increasing avenues for commercial viability.

Later, Krueger’s examination turns toward who musicians actually are. And while his findings centre around the lives of musicians in the US, the profile of a musician’s working life – typically lowly paid, financially insecure – has the ring of truth for musicians on our own fair shores too.

As he explains, musicians are more likely to be affected by substance abuse and mental health issues, owing to the aforementioned financial difficulties, as well as life on the road and availability of drugs and alcohol.

He does note, however, that success in music is also a major contributor to upward mobility, with 26.5 percent of Billboard Top 100 artists in 2016 coming from the bottom 10 percent of all families economically (again, American focussed – it would be interesting to see if these percentages are reflected in Australia).

For those who do break through and become commercially successful, life is especially sweet for those right at the top. Krueger sums up the point neatly:

“Some have argued that the music industry has become more egalitarian because of streaming, computer music technology, and lower entry costs. But as far as artists’ incomes are concerned, it is becoming more unequal.”

He goes on to point out that the top one percent of artists garner more than half of all ticket revenue, on account of the amount of that they are able to charge for their tickets. This, sadly, is one the statistics that most accurately reflects the broader economy.

But, with more of the live music industry focussed within festivals, this is helping to give emerging artists a platform to compete with more established acts. Krueger argues that festivals, with their sharing of infrastructure like staging and lighting and their lifespan (with single events able to run for several days), are much more cost effective to run, and should enjoy continued popularity.

Emerging musicians should also take heart from the fact that streaming, as Krueger puts it, “is not close to reaching its saturation point.” And though there have been and will continue to be arguments on the payments from streaming, paid subscriptions to various services continues to rise, with even more ad-based subscribers. In short, the pie is growing.

Later Krueger illuminates the field of copyright protection. As is the case in emerging tech, the tenets of intellectual property have played an incredibly important role in the emergence of popular music throughout history. Even operas were produced more often in nineteenth-century in Italian states that were protected by copyright laws. The myth that artists will create regardless of whether or not there are state protections for their creations is not borne out by the statistics.

In compiling Rockonomics, Alan B. Krueger sought comment from a broad and knowledgeable cross-section of the industry. From John Eastman – brother-in-law and lawyer for Paul McCartney, Gloria Estefan, Cliff Burnstein – a partner in Q Prime management and manager of Metallica, Bill Zang – a luminary of the Chinese music industry (which Krueger identifies as having world changing potential) and more. And while the research is deep, the overall tone exudes lucidity and authority, befitting Krueger’s status as a preeminent economic communicator.

Perhaps it’s telling that Krueger sums up his economic exploration by highlighting the fact that above all, music is a great bargain. The entire pop music canon is available billions of humans, basically for free. He mentions that, “The average consumer spends less than a dime a day on recorded music. Yet the average person spends three to four hours a day listening to music.” Not a bad deal at all.

So while times have never been so good for consumers, how about creators? Well, the same pitfalls that have always been there – mismanagement, lack of control, financial insecurity – stubbornly persist. Yet, as Rockonomics deftly explains, knowledge of economic principles can give us strategies to navigate a sustainable life in music.

Rockonomics is out now via Hachette.