Albert Hofmann was an ambitious young man. Each day he set off on his bicycle to ply his trade at Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in Basel, in the shadow of the Swiss alps. His expertise lay in synthesising chemical compounds for medicinal purposes.

On a fateful day in 1938 (under pressure from his boss who was focussed on commercial imperatives) Hofmann was tasked with creating a new fusion which blended alkaloids of ergot, lysergic acid and diethylamide. LSD was born.

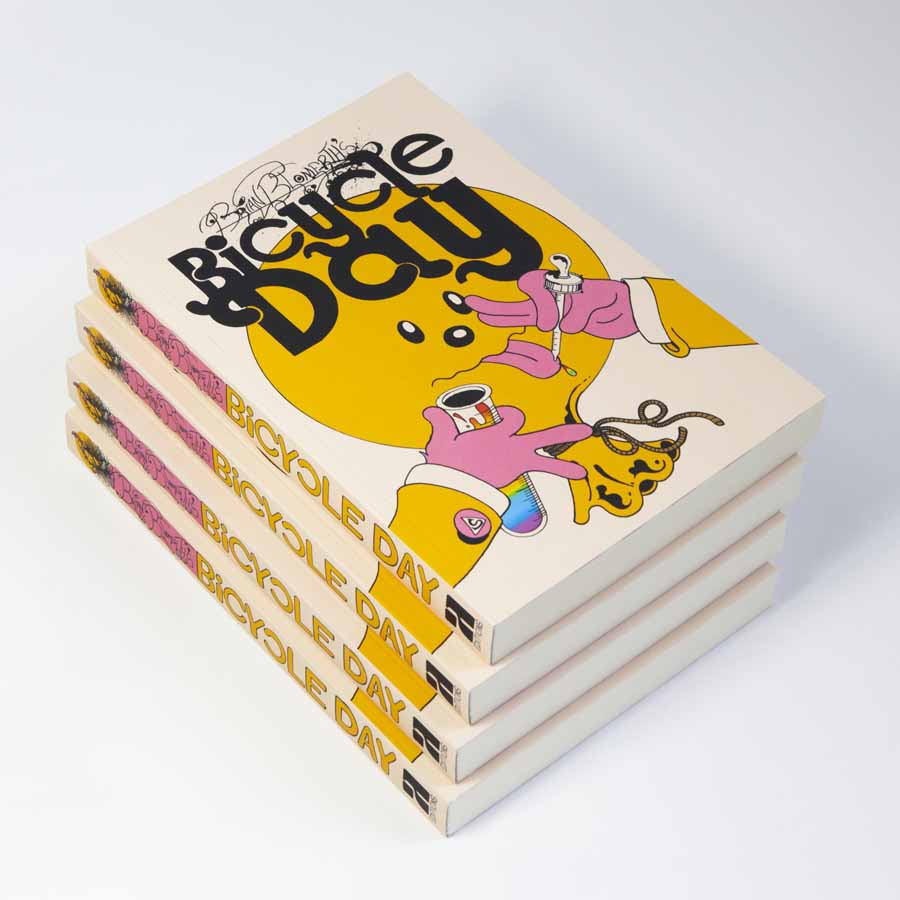

Heralded as a triumph of science only to be brutally repressed, the story of LSD is one that few know. Brian Blomerth’s Bicycle Day tells the tale with colours that reach into the subconscious.

Brian Blomerth has recreated the significant epoch with a singular touch that only an artist of his pedigree could accomplish. He calls himself a “comic stripper” – a moniker that which underscores his irreverent approach. The Brooklyn native’s work has been a fixture of the underground comic scene, featuring in zines and gracing album covers. Bicycle Day deftly synthesises Blomerth’s eclectic experience.

Another aspect of Blomerth’s achievement is the fact that he manages to create such an expansive tribute to Hofmann in what are really just three days in his life. The first of which was November 16, 1938 – the day of Hofmann’s first experiment with ergot alkaloids.

On this seemingly innocent morning the Swiss countryside is beautifully rendered in Technicolour and Hofmann’s universe populated with floppy-eared, humanised dogs indulging in rich double-page spreads. It’s luxurious.

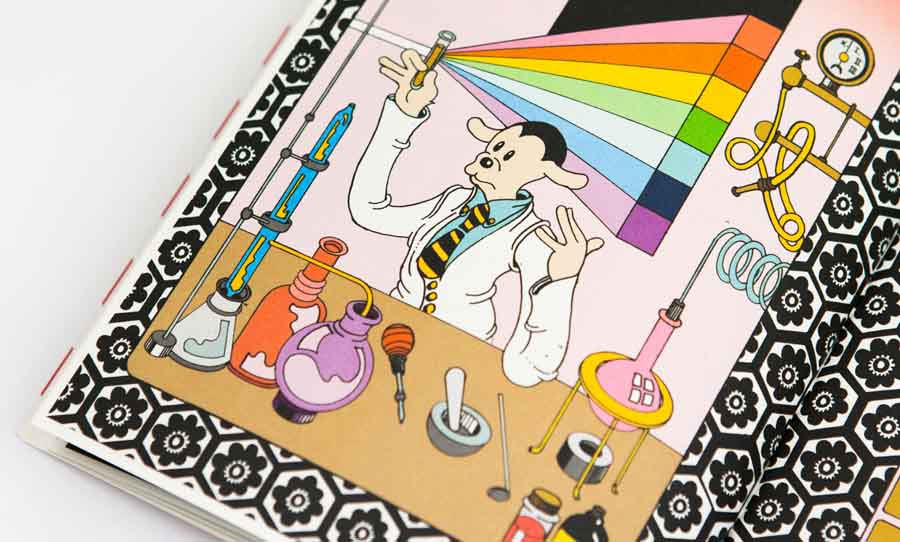

Far from glossing over the historical facts though, the chemist’s experiments are spelled out in detail. In the Confessions section at the end of the book, Blomerth admits to failing high school chemistry. The specifics of the formulas that Blomerth has included however, serve to remind us that Hofmann wasn’t seeking to create psychedelic history – this was hard science.

The book’s introduction also frames the story with valuable historical and scientific context. It’s author, Dennis McKenna is a distinguished ethnopharmacologist and leading voice on the responsible use of psychedelics.

He argues that, “[LSD is] one of the most significant tools ever discovered for the understanding of the mind and consciousness.” Which makes its historical setting – one of the most inhumane periods in our history – such a striking paradox.

Our humble hero was also a family man. Bicycle Day illuminates Hofmann’s rich relationships with his wife Anita and his children, recounting the day to day banalities of breakfast and the school run.

But in the years between LSD experiment’s false start and its ultimate success the scourge of war turned his idyllic existence upside down. The story doesn’t resume until April 16, 1943 – with the war in full swing and paranoia about a Nazi invasion high.

After a chance meeting with rival chemist, Paul Hermann Müller, who is developing DDT – another compound that would have far reaching historical consequences for entirely different reasons – Hofmann is spurred on to revisit his five year old experiment (Blomerth admits in his confessions that the depiction of Müller as a bully was for dramatic effect).

The book’s artwork then ascends into the psychedelic, as Hofmann inadvertently infects with himself with LSD, blaming his boss “for being too cheap to pay for a real ventilation system.” The comparatively natural and subdued pastels that set the tone for the first act give way too deep magentas and blues. Albert Hofmann is sweating and nauseous on his bike. Pigs and snakes are dancing by the side of the road. He’s tripping hard, but doesn’t know it.

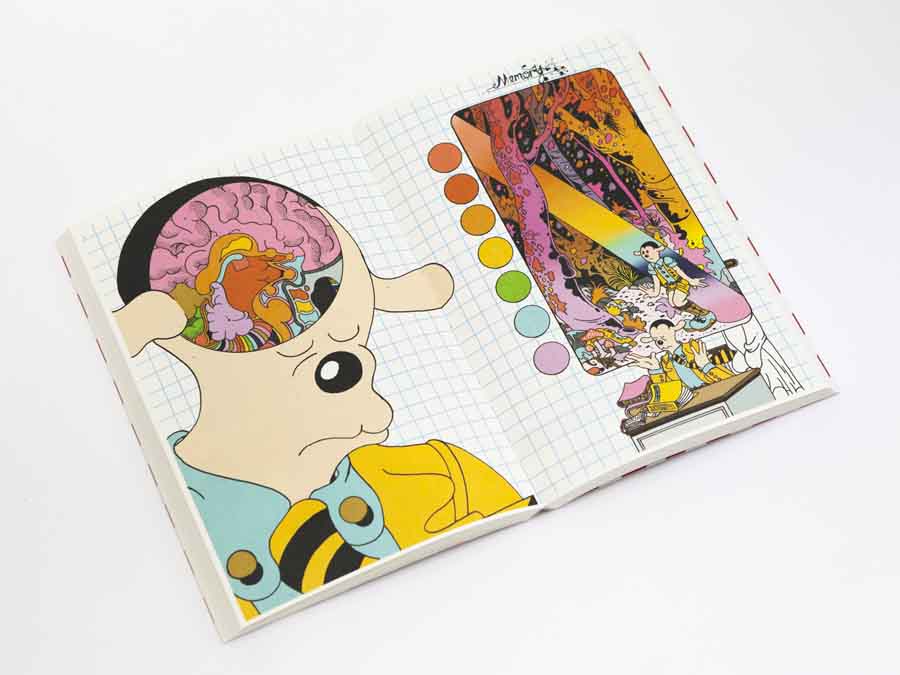

Three days later on April 19, his family leaves Basel for the relative safety of Lucerne – away from the borders of war torn France and Germany. In a moment of clarity, Hofmann realises what has happened – his perceived experience of illness, the hallucinations that were swirling pink and green in his mind – were actually caused by his chemical recipe.

With the family safely tucked away, the scientist purposely ingests a dose of LSD (as McKenna mentions in the introduction, he took quite a liberal amount). Then, ably chaperoned by his assistant Susi, a new dimension is literally unzipped: Bicycle Day begins. His high deepens further and further until Albert is separated from himself, even questioning if he’s still alive: “Am I dead? Is this the transition?”

Blomerth’s mastery of colour comes to the fore in this sequence – the fluorescent pinks and greens of Hoffman’s first accidental trip are back along for the ride. As the experience continues, the black, tormenting presence of his nemesis, Paul Hermann Müller torments him, “Tsk tsk! A young chemist killed by his own creation!”

The concluding pages reveal the chaos and panic of Hofmann’s adventure, building up to a climactic cacophony – then exhaling into watercolour daydream. Hofmann is newly awake in a world where, “Everything glistened in the soft, fresh light.” If you take Brian Blomerth’s Bicycle Day for a ride, you’re likely to see the world differently too.

Brian Blomerth’s Bicycle Day is out now, via Anthology Editions.