PAX, the mega-conference in gaming, attracted the elite in development, top-notch indies and around 70,000 fans to the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre last month.

The Aus Indie Showcase highlighted the best and brightest among local independent games. Among this cream of the crop was Death Hall from developer Thomas Janson. Death Hall is a classic platformer, made for iOS, complete with a unique pixel art visual aesthetic and a deep, immersive soundtrack by Gareth Wiecko.

The pair took time to explain the origins of Death Hall from a visual and sonic perspective, the challenges of creating a game specifically for mobile and the tools needed to create an atmosphere where life constantly hangs in the balance.

Thomas Janson and Gareth Wiecko chat Death Hall, a spooky new adventure for iOS. The guys share their inspirations and talk about the challenges that come with creating a classic platform game.

ENMORE AUDIO: What sparked your interest in creating games?

THOMAS: From the moment I discovered a 3D program called Blender in high school, I was building levels and tinkering with the integrated game engine. I’ve always played games but that’s not why I like making them. I was the kid in school who spent hours trying to create the perfect paper plane, so I think putting my energy towards making things is just a part of my DNA.

ENMORE AUDIO: Can you tell us what inspired the visual choices for Death Hall?

THOMAS: Death Hall is hand-drawn in my own weird, wacky style. It came naturally to me to design the dungeons, lairs, and enemies the way I did. I’m a character animator, but I can’t draw, so I had to spend a lot of time refining shapes and colours to design appealing characters and game objects.

In the end, I came to learn that strong shapes and contrasting detail is what made Death Hall pop visually, so I pushed those aspects of the artwork to make a game that visually shone, but didn’t distract the player with too much visual chaos.

ENMORE AUDIO: Why iOS? Do you have a particular affinity with mobile games?

THOMAS: I wrote the game in an engine called Cocos2d. It’s sort of well-known but not really. I’ve been using that engine for years as it’s easy to prototype quick ideas, however, it’s limited to iOS.

I regret not learning a more mainstream game engine earlier in order to publish to multiple platforms, but now that I’ve been using Cocos2d for a long while, learning another engine is mostly a matter of adjusting to a different workflow.

I would say that after my upcoming game Sneak Master, I’m done with mobile games. I want to try something different, and stretch my design muscles on different platforms ie: console and PC.

ENMORE AUDIO: What are some of the challenges in creating a platform game?

THOMAS: A good platform game is deceptively tricky to craft. In Death Hall, a major challenge was caused by having rotated and undulating platforms. It meant that enemy spawning, platform collision detection, hazard placement, platform layout, and level stitching all became challenges of their own.

Couple that with trying to design a game that is fun and highly responsive on mobile, and you’ve got a hard task ahead of you. Also, the usual suspects such as pre-collision and post-collision jump registration, which are clever ways to make games feel much more responsive.

These tricks mean the player can tap jump a couple of frames before landing on a platform, or a couple of frames after falling off a platform, and still jump successfully. Without these features, a platform game becomes absolutely unplayable. There are more tricks, but those are the most interesting ones and the most satisfying to implement as a developer.

ENMORE AUDIO: Are you working on a new game at the moment?

THOMAS: I am! It’s called Sneak Master and it’s a simple speed-stealth game on iOS. After Death Hall, I wanted to decompress and make something fun and light. Sneak Master is feature complete and will be released sometime in January next year.

ENMORE AUDIO: Over to you, Gareth. How did you get into game audio?

GARETH: I’ve been playing games passionately as far back as I can remember. I have this fond memory of watching my parents playing Atic Atac for the Spectrum when I was really young! As I got older, I’d digest as many games as I could, studying the soundtracks and trying to realise what the composer was trying to convey.

In my teens, games like the early Monkey Islands, Fallout 1 + 2, and both Baldur’s Gate games had a huge impact on my passion for audio. Final Fantasy scores would seep in as I grew older and I’d always be tinkering on the piano, trying to replicate the feel of certain tracks. As the years went on my passion for indie dev and the composers that would work in these fields grew rapidly.

After finishing up a Bachelor of Composition in Melbourne and writing music for a few shorts films and ballets, I decided to take the jump and start getting more involved in the indie game world in Australia.

ENMORE AUDIO: What inspired the sound world of Death Hall?

GARETH: Thomas was great to communicate with. He’d send videos and stills of the game prior to me starting to give me an idea of the aesthetic. We’d talk a lot via email (as he was based in Sydney) to discuss each area of the game in finer detail. Having played a lot of games, I’d send him a few levels from other games that I could hear in a similar vein and we’d go from there.

The whole process was really organic, I’d produce a few rough demos of each area and Thomas would get back to me on parts that he thought would and wouldn’t work. Each level was quite distinct, so I’d go about creating a particular hook for each world.

ENMORE AUDIO: How do you create sounds that are particular to this environment?

GARETH: Each area in the game was trying to convey a different aesthetic. Both the visuals and descriptors from Thomas for each level had a distinct idea, so I’d have a new session for each one, rarely using elements from other sessions.

The descriptors were a big help in getting each one started. The first world would have the monster burst out and chase you and Thomas wanted the same piece in two elements so that it would surprise you the first time. So I’d compose the first half using fewer elements and energy and the latter with irregular time signatures for the rhythm and a wider spread of textures.

The second world was a damp, gritty cave so I’d sample droplets to use as a percussive element and over-process some sounds to add a gritty texture. Each area was a blast to work on as I was able to really explore my creative palette!

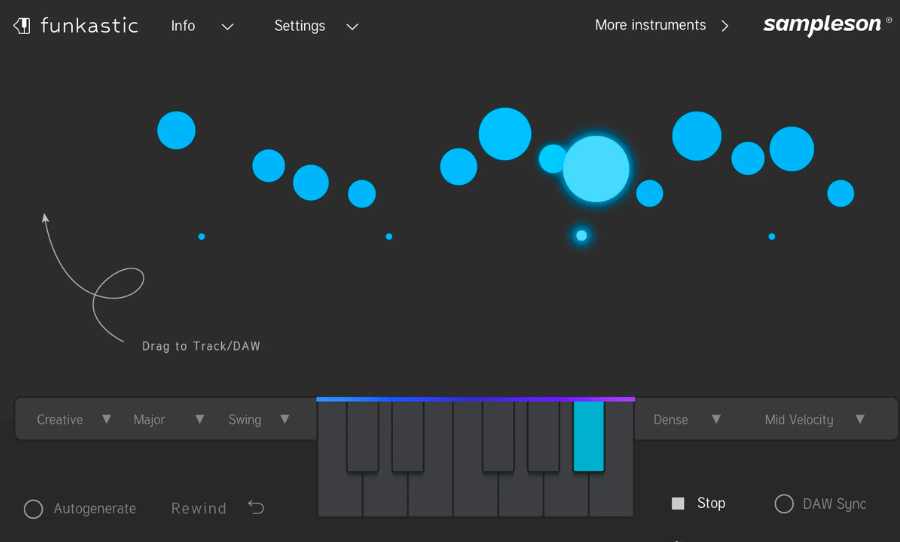

ENMORE AUDIO: What gear is essential for you?

GARETH: Ableton is my DAW of choice and some of the stock instruments they have are incredible. I pair that up with my Arturia Keylab 88, I picked it up about a year ago and the weight action is delicious. As far as piano tone goes, I really like the grand piano tone on Keyscape. I also use some of the Kontakt instruments via Native Instruments and some string patches through Spitfire Instruments.

ENMORE AUDIO: How do you see the division between sound design and music? Are they separate or do they inform each other?

GARETH: I think each game comes with its own set of parameters, and the synergy between design and audio is entirely dependent on the game itself. I was recently playing Mini Metro where the sound design was cleverly weaved into the music to create this beautiful ambient harmony.

To compare that to say a fantasy RPG, where you’d need the SFX of the world to stand separately to the score comes with its own set of challenges. The challenge comes with finding that balance and understanding the vision.

ENMORE AUDIO: What are the challenges in maintaining tension through music?

GARETH: To compare the audio of (as an example) a horror survival game next to an ambient puzzle game, both would come with their own set of challenges. I think it’s important for the composer to realise the vision of the game alongside the developer, and not have either element overshadow the other.

I’d define tension as maintaining interest – as long as a piece doesn’t become too repetitive and doesn’t stray too far from the narrative – then I’d consider you to be completing your role. Some games require long tracks that are constantly varying, others require three to four-minute loops that keep the player invested. It’s the composer’s role to maintain that level of interest depending on the brief.

ENMORE AUDIO: What are your future goals in game audio?

GARETH: I’m currently looking for another game to score at the moment (here’s looking at you game devs!) with the intention of attending the Global Game Jam here in Melbourne early next year.

My main passion is working within the indie scene and realising the vision alongside developers. There are some great games coming out of Melbourne and the rest of Australia, and I’d love to get involved with some teams over the next few years!

Death Hall is out now via the App Store. Visit the website for more details.